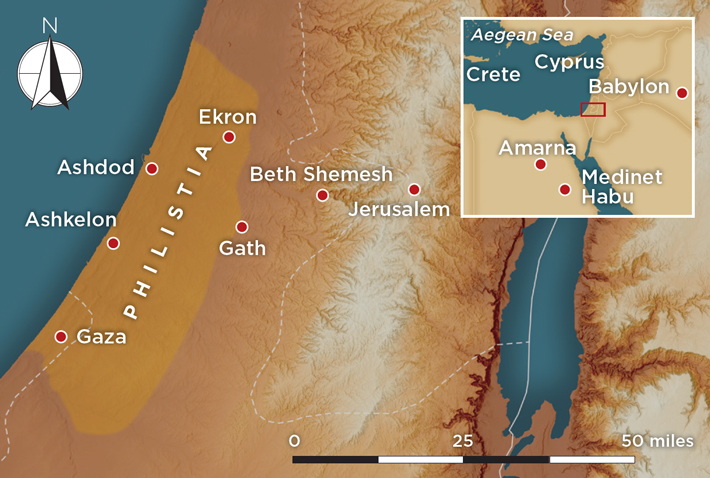

In the heat of the day, a glint off the Mediterranean is just visible from the top of a mound known as Tell es-Safi that rises some 300 feet above Israel’s coastal plain. For generations, scholars believed that the stretch of Mediterranean coast west of Tell es-Safi was once the landing point of multiple invasions by the Israelites’ dreaded nemeses, the Philistines. First emerging in the southern Levant around 3,200 years ago, the Philistines were long thought to have been descendants of invading groups that scholars refer to as the “Sea Peoples.” In the twilight of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1550–1200 B.C.), these groups raided Egypt and conquered the cities of the Semitic Canaanite people who lived on the coast of what is now Israel and the Palestinian territories. A final wave of Philistine invasions was thought to have reached the coast of Canaan early in the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.), around 1175 B.C. The ruins of Gath, a Canaanite center that became the Philistines’ mightiest city, now lie beneath Tell es-Safi, which means “white hill” in Arabic. The mound’s white chalk cliffs, which overlook fertile farmland, inspired the Crusaders to name the castle they built there in the twelfth century A.D. Blanche Garde or White Fortress. Until the war that followed Israel’s founding in 1948, the tell was home to a small Palestinian village whose ruins are now overgrown with thorns.

Gath was one of five cities known as the Philistine Pentapolis, which thrived during the Iron Age (ca. 1200–539 B.C.). Until archaeologists began to excavate the cities of the Pentapolis, also known as Philistia, the Philistines were largely known through the work of the scribes who first began to write the books of the Hebrew Bible hundreds of years after the Sea Peoples reached the Levant. These scribes cast the Philistines as the Israelites’ uncircumcised, pagan archenemies, who fought against some of the Bible’s most prominent figures. According to the Bible, the Israelite judge Samson slew 1,000 Philistine warriors with the jawbone of an ass and pulled down the pillars of a temple to Dagon, the principal Philistine god. After the Philistines had captured the Ark of the Covenant, Saul, Israel’s first king, fell on his sword rather than be taken captive. Saul’s son-in-law and eventual heir, King David, dueled with the Philistine hero Goliath of Gath and felled the giant with a slingshot. The Bible’s pejorative depiction of the Philistines has so pervaded Western culture that, more than 3,000 years on, “philistine” remains a byword for an unsophisticated person indifferent or hostile to artistic and intellectual pursuits.

Finds from limited excavations during the early twentieth century pointed archaeologists to the Aegean as the Philistines’ original homeland. The conquerors, they imagined, were Mycenaeans, members of the Late Bronze Age culture of ancient Greece remembered in the epic poems of the Trojan War, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Since the 1990s, archaeologists have extensively excavated four of the five cities of the Philistine Pentapolis: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath. Only Gaza, which is located beneath the modern Palestinian city of the same name, remains unexcavated. These digs, particularly the long-term excavations of the ruins of Gath beneath Tell es-Safi, have helped archaeologists tell a more nuanced story about the origins of the Philistines, which may lie in a series of mass migrations rather than waves of conquest. “Understanding the Philistines as this singular, unified migratory group that came from somewhere in Greece, landed on the coast, and conquered the Canaanite cities no longer makes sense,” says Bar-Ilan University archaeologist Aren Maeir, who directs the Tell es-Safi excavations.

Maeir and many of his colleagues suggest that the Philistines were an eclectic and multiethnic group of migrants, not a uniform horde of invaders. He believes it’s likely they hailed from various locations around the eastern Mediterranean and moved to the Levant over many decades between the late thirteenth and mid-twelfth centuries B.C. They settled, mostly peaceably, among the local Canaanites, creating a distinct hybrid culture that endured for much of the Iron Age. “What we’ve learned about Philistine culture at Gath,” Maeir says, “is that the process of its origins, formation, transformation, and development is much more complex than was originally thought.”

For centuries before the arrival of the Philistines, Egypt dominated the Semitic peoples of Canaan. Canaanite city-states, including Gath, were ruled by client kings loyal to the pharaoh, and key ports such as Ashkelon housed large Egyptian garrisons. Among archives of fourteenth-century B.C. correspondence found at the Egyptian capital of Amarna are at least 11 letters from two of the king’s vassals in Gath. “I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, my god, my sun, seven times and seven times,” Shuwardata, the Canaanite ruler of Gath, writes in a missive imploring the Egyptian pharaoh to send reinforcements to quell a local insurrection.

Like the Israelites living in the inland hill country to the east of Gath, the Philistines first appear in the historical record during the upheaval of the end of the Late Bronze Age, around 1200 B.C., when a period of stability in the eastern Mediterranean marked by long-distance trade and diplomacy came to a dramatic end. The Hittite Empire that had ruled Anatolia since about 1750 B.C. collapsed. The Egyptian grip over Canaan began a long decline, after which some Canaanite cities were destroyed. Scholars debate what precipitated this Late Bronze Age collapse. Maeir says there likely wasn’t a single root cause, but that a combination of environmental and social factors were to blame. Analysis of pollen and sediments from Bronze Age sites in Greece and Israel shows that the eastern Mediterranean experienced a period of severe aridity starting around 1250 B.C. Protracted periods of drought and famine likely fanned social unrest and may have triggered mass migrations and invasions that undermined the political stability of the Late Bronze Age.

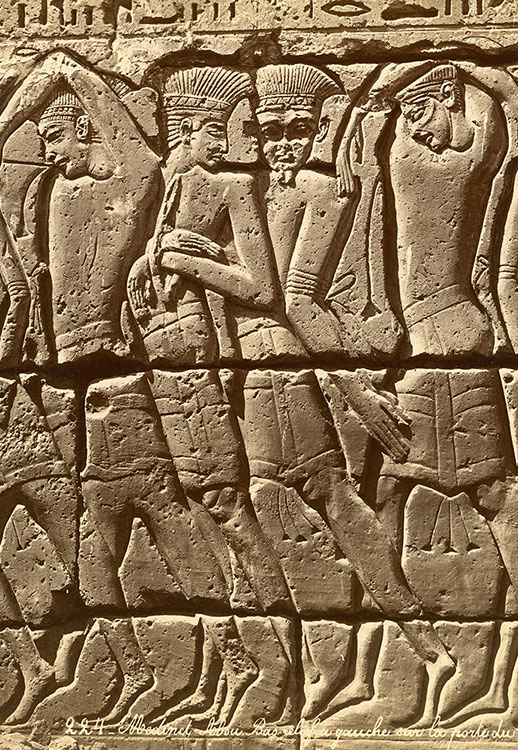

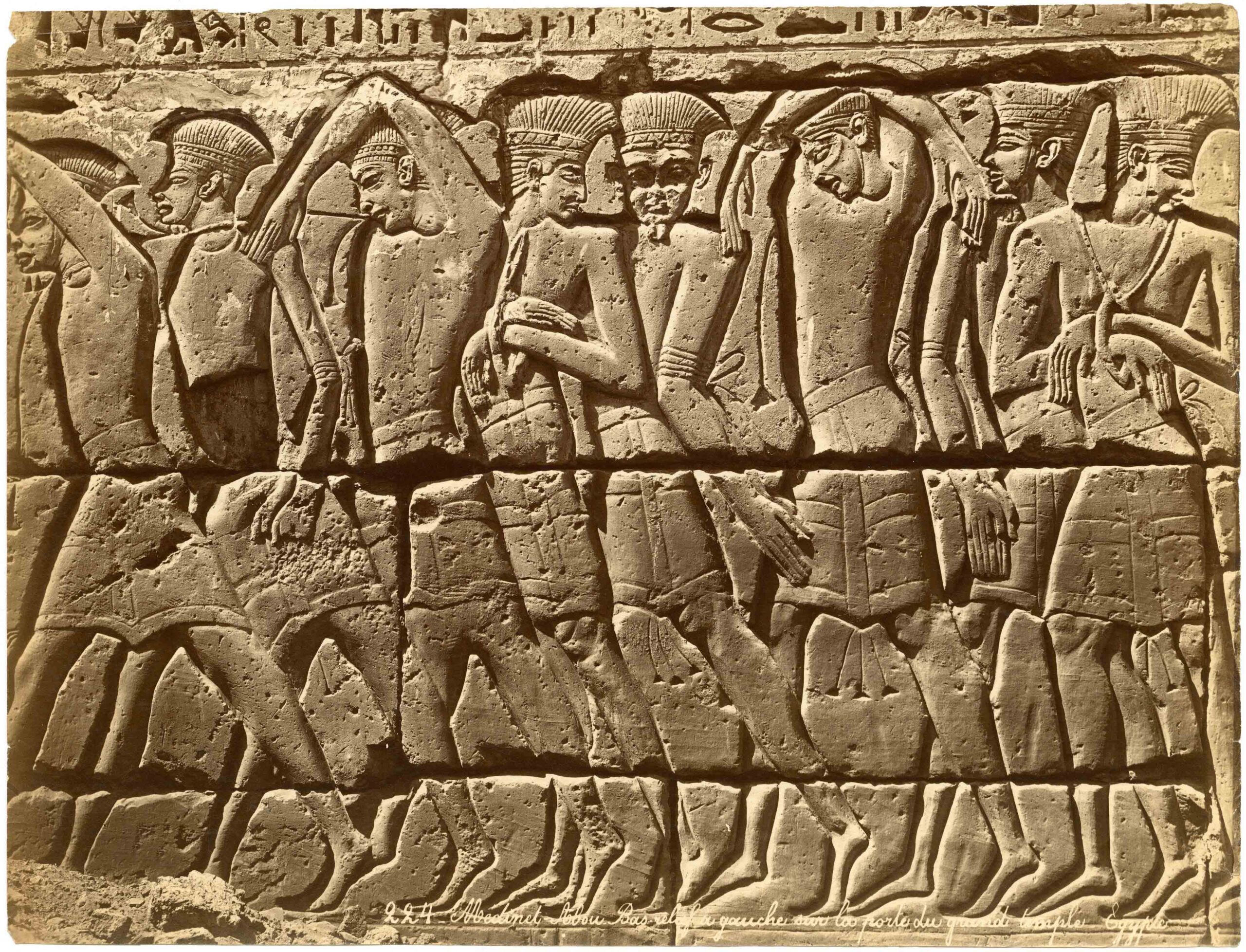

Inscriptions on the walls of Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu tell of battles in the early twelfth century B.C. against the Sea Peoples, who are depicted on reliefs engaging the Egyptians in naval combat. These warriors wear feathered and horned helmets and fight from ships whose prows are decorated with carvings of birds’ heads. Among the names describing the Sea Peoples inscribed at Medinet Habu is Peleset, which nineteenth-century scholars first linked to the biblical Philistines. Biblical texts offered early researchers further clues about who the Philistines were. Their leaders are referred to by the title seren, which scholars once believed may be related to the Greek term tyrannos, or ruler. According to the Bible, the Philistines arrived from the island of Caphtor, which may be the Greek island of Crete.

Early twentieth-century archaeologists made a number of discoveries that seemed to reinforce biblical and Egyptian descriptions of the Philistines. Excavations at Ashkelon and Beth Shemesh—an Israelite city east of Gath mentioned in the Book of Judges as the location to which the Philistines returned the stolen Ark of the Covenant—unearthed early Philistine ceramics that closely resemble types of Mycenaean pottery found throughout the Aegean. These early Philistine wares feature geometric patterns in red and black and are sometimes decorated with depictions of birds’ heads akin to those in the Medinet Habu reliefs. The Mycenaeans are known to have used these vessels for drinking and feasting, and the Philistines likely used them in the same way. Although these ceramic vessels provided the first firm connection between the Philistines and the Aegean world, later examinations of other pieces of early Philistine pottery revealed that they were crafted from local Canaanite clay. From the beginning, then, Philistines were adapting their culture to local conditions.

During more recent excavations at Philistine sites, scholars have made discoveries that speak to both the origins of the Philistines and the development of their culture. In the past quarter century, Maeir and his team have opened more than 100 excavation squares at Tell es-Safi, each measuring 16 by 16 feet. In the process, they have unearthed monumental fortifications including a massive gate, as well as metalworking facilities and a Late Iron Age temple, all of which demonstrate Gath’s importance in the southern Levant during the Philistine era. The team has found that in the centuries following the Philistines’ arrival, Gath grew and, at its peak in the ninth century B.C., was home to an estimated 10,000 inhabitants. Jerusalem, by comparison, would not reach that size until the eve of its destruction in 586 B.C. Gath’s location straddling trade routes that connected inland copper mines with the coast likely contributed to its status as the most important member of the Philistine Pentapolis and made it one of the most significant city-states in the southern Levant.

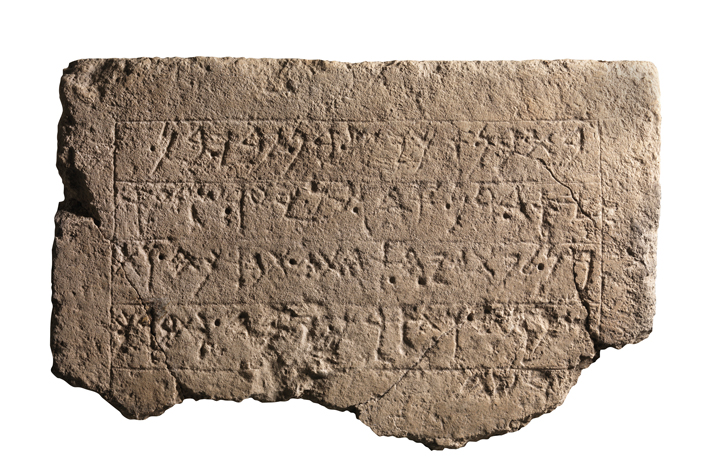

Other discoveries have helped Maeir and his team develop a more nuanced take on Philistine culture. Among their most important finds is a ninth-century B.C. two-horned altar, which combines decorative elements from the Levant with those known from Cyprus and the Aegean. It is the oldest such altar in Philistia. The team also found a sherd bearing inscriptions written in Canaanite script with two names that are close to Goliath, suggesting that the now-famous name may have been common in Philistia. At the same time, they have discovered copious amounts of Canaanite pottery and other artifacts dating to the earliest stages of the Philistine period. The picture of Philistine Gath emerging from recent excavations, says Maeir, is one of a vibrant metropolis where migrants from around the Mediterranean lived cheek-by-jowl with Canaanites. For several generations, these two distinct cultures coexisted before combining into one.

Maeir’s vision of the Philistines isn’t the only one embraced by modern archaeologists. Wheaton College archaeologist Daniel Master, who codirected recent excavations at Ashkelon, the Philistine port 18 miles west of Tell es-Safi, believes Egyptian and biblical accounts should be interpreted more literally. He thinks that the Philistines likely hailed from Crete and conquered Canaanite cities during a brief window around 1175 B.C. Philistine pottery resembling ceramics from Mycenaean sites was a product of a single stylistic moment, Master says. Those pottery types and decorative styles, he thinks, changed in parallel in Philistia and the Aegean during a single generation.

The 2013 discovery of a cemetery at Ashkelon, the first large burial ground to be excavated at one of the cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, has helped bolster Master’s view. This cemetery contained some 200 burials dating to the Philistine period in which individuals were interred separately. This is unlike Canaanite funerary practices in which the dead were cremated or buried collectively in pits or tombs. Genetic analysis of these remains, says Master, supports Egyptian accounts of the Philistines’ origins. He was part of a team that analyzed the DNA of 10 individuals found in the Ashkelon cemetery: three dating from the Bronze Age, four from the Early Iron Age, and three dating to the tenth to ninth century B.C. The team found that DNA sampled from the Early Iron Age burials had a European genetic component that set the people apart from the local Bronze Age Canaanite population and supports the idea that the Philistines originated in Crete.

University of Melbourne archaeologist Louise Hitchcock, who directed excavations in a residential district at Tell es-Safi, remains cautious about the Ashkelon DNA findings. She points to the study’s small sample size. “I don’t think you can say they were Philistine based on their DNA,” Hitchcock says, “but you can based on their full realm of material culture.” In recent years, finds from Gath, Ekron, and Ashkelon have all suggested that Philistine culture was eclectic and had parallels in Late Bronze Age cultures from throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Researchers have analyzed dog bones from Philistine sites that suggest that, like pigs, dogs were part of the Philistine diet, as they were across the Aegean and Anatolia. Nonlocal flora from around the Mediterranean, including sycamore, poppy, and cumin, first appeared in the Levant at Philistine sites. Some finds, such as circular pebbled hearths similar to those found in the center of homes in Greece and Cyprus, cult objects such as figurines of goddesses with their arms raised in a shape resembling the Greek letter psi (Ψ), and Cypriot-style notched cow scapulas possibly used in soothsaying, underscore that the Philistines were connected to the ancient Greek world. At the same time, a seated female figurine discovered at Ashdod featuring an unusual combination of Aegean and Levantine styles demonstrates the rich combination of cultural influences that permeated the world of the Philistines.

Early Philistine culture does not feature the hallmarks of one particular place of origin—a single cultural package of ritual objects, ceramic styles, and social customs, Maeir says. “Rather, we seem to have a little bit from Greece, and a little bit from Cyprus, and a little bit from Crete, and from Anatolia and other places.” At the same time, Canaanite cultural practices that predate the Philistines, such as placing an oil lamp within a bowl and burying it beneath the floor of a building as a kind of offering, continued uninterrupted after their arrival.

Hitchcock says the archaeological record doesn’t neatly match the traditional scholarly accounts of Philistine invasion and colonization. In particular, she points to the absence of evidence of violent conquest at Philistine sites, including Gath. “We go straight from early Philistine layers down into Late Bronze Age layers with no evidence of destruction,” she says. “This calls into question the whole myth of the Philistines as an invading force of Mycenaean colonizers sweeping in and taking over.” In addition, very few weapons have been found at Philistine sites, an absence that challenges the martial image of the Philistines presented in the Bible.

Maeir and Hitchcock propose that the people who became the Philistines were part of migrating populations who formed opportunistic pirate tribes. These groups may have roamed the Mediterranean, taking on followers from a number of different disrupted societies. “When Egypt loosened its grip on Philistia, these groups finally settled in among the local population,” Hitchcock says. The scholars believe that some of the peoples who comprised the Philistines were multiethnic groups of raiders possibly analogous to Atlantic pirates of the seventeenth century A.D., who are known to have come from many different nations.

These Late Bronze Age pirates may have spoken different languages and chosen particular symbols that bound them together as a group in the way many early modern pirates rallied to the Jolly Roger. The Aegean-style drinking and feasting ware found at Philistine sites, Maeir and Hitchcock suggest, may have served as just such a symbol. They point out that feasting was an important feature of Bronze Age society and played a central role in the culture of more recent pirates as well. It’s also possible that the feathered and horned helmets and the birds’ head prows depicted on the Medinet Habu reliefs served as potent symbols that a diverse group of pirates could rally around. The scholars further suggest that seren, the word describing the leaders of the Peleset chiefs on the Medinet Habu reliefs, may not come from the Greek word tyrannos after all. Instead, they believe it may be related to the word tarwanis used by the Luwian people of southern Anatolia to describe warlords. Perhaps it was these Bronze Age Blackbeards who became the first Philistines.

According to the Bible, once-mighty Gath fell in the ninth century B.C. to King Hazael of the Aramaeans, a Semitic people who dominated what is now Syria. Maeir and his team have found siege works encircling Tell es-Safi that date to this time and suggest that the people of Gath faced a protracted conflict. Though the Philistines abandoned Gath, their distinct culture lasted in some form in the other cities of the Pentapolis for almost 300 years. The discovery of a seventh-century B.C. royal inscription at Ekron written in Canaanite but including the Philistine name Achish is clear evidence that the Philistine presence endured well after the fall of Gath.

Then, in 604 B.C., the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 B.C.) laid the remaining Philistine cities to waste and sent the Philistines into exile in Mesopotamia, along with the conquered Judeans. Sixth-century B.C. cuneiform tablets have been unearthed near Babylon in modern-day Iraq that describe people as “men of Gaza” or “men of Ashkelon.” This suggests that Philistines may have lived near the city and, perhaps, preserved their identity to some extent for a century or more. But their descendants never returned to Philistia and they assimilated into Babylon’s local population, leaving it to archaeologists to reclaim their story from their Egyptian and Israelite enemies.