At the site of the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu in present-day Tello, in southern Iraq, stands a mound known as Tablet Hill. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, French archaeologists excavated tens of thousands of cuneiform tablets there. Looters made off with thousands more. These tablets were known to have been the administrative archives of a palace that had never been located. Given the extent of the looting that had taken place at the site, many believed there were no significant archaeological remnants left.

Based on his experience excavating a nearby temple to the warrior god Ningirsu, however, British Museum archaeologist Sebastien Rey had a hunch that the earlier archaeologists’ spoil heaps might have protected portions of the site. “We tend to say that the big sites excavated in the nineteenth century have been excavated away, that there’s nothing left to find,” he says. “But there are many treasures that we can still discover—and it’s our responsibility to go back to these sites with the technologies that we have to salvage what can be salvaged.”

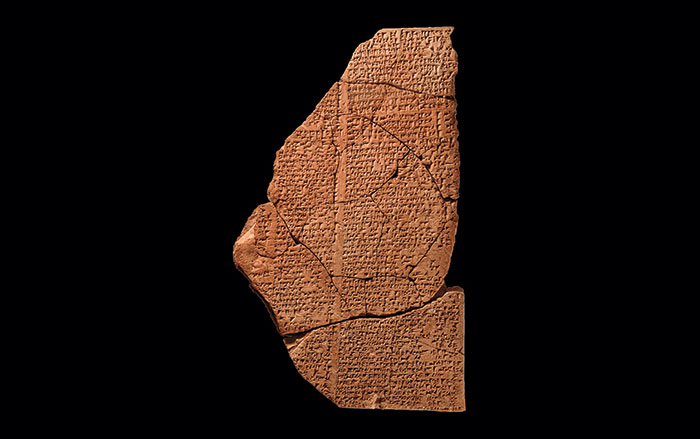

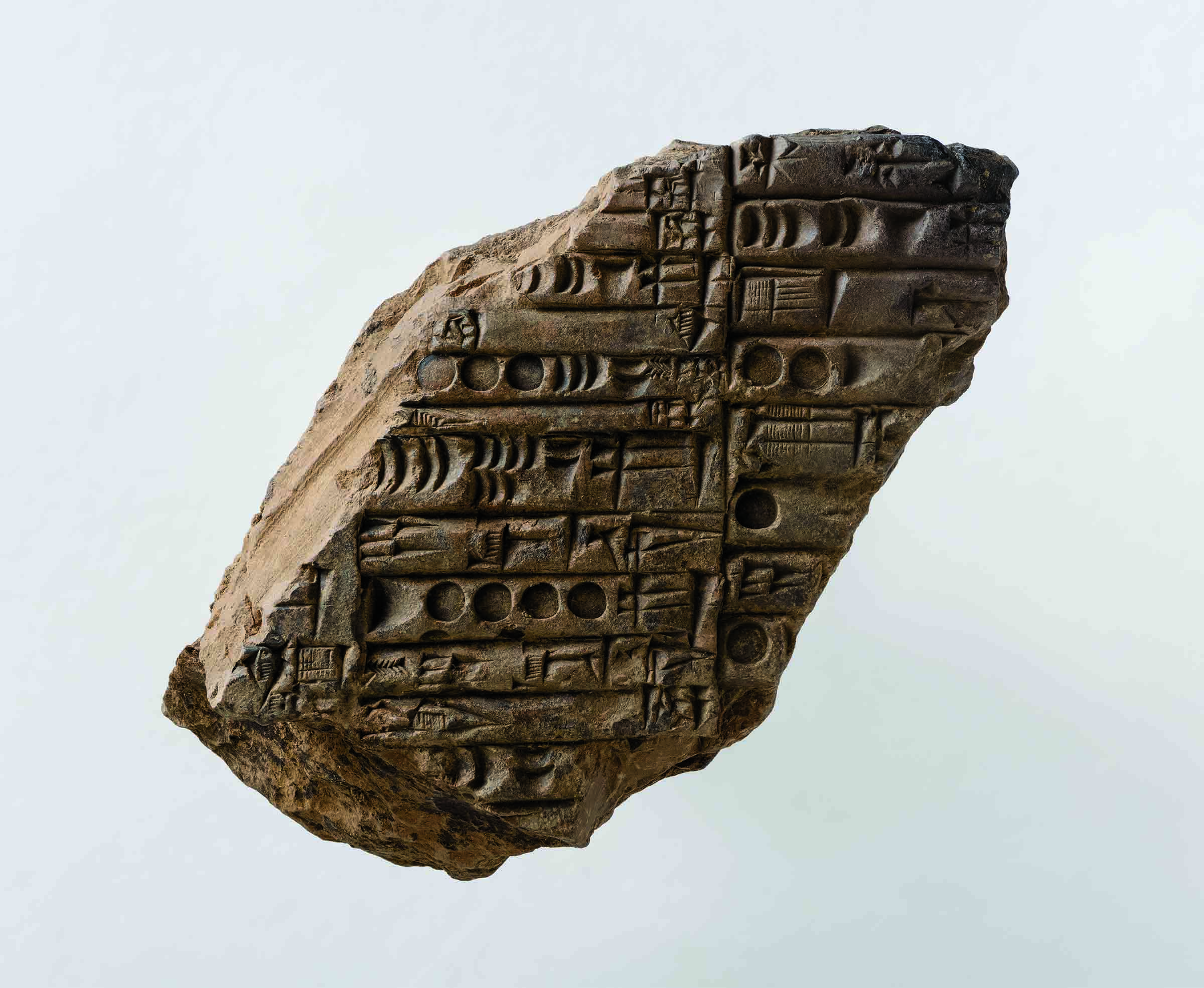

Using drone photography, a team of British and Iraqi archaeologists led by Rey identified potential structures at Tablet Hill. They then dug a single trench across the mound, revealing a section of palace wall dating to the beginning of the second millennium B.C., around the time the city was abandoned. A few feet deeper, at the other end of the trench, they identified a portion of wall dating to the mid-third millennium B.C. The team also excavated and conserved more than 200 additional cuneiform tablets. Rey suspects that, like many large ancient Mesopotamian mudbrick structures, the palace was heavily renovated or even rebuilt over the centuries.

Click below to see a video from the British Museum about archaeological work at Tablet Hill.