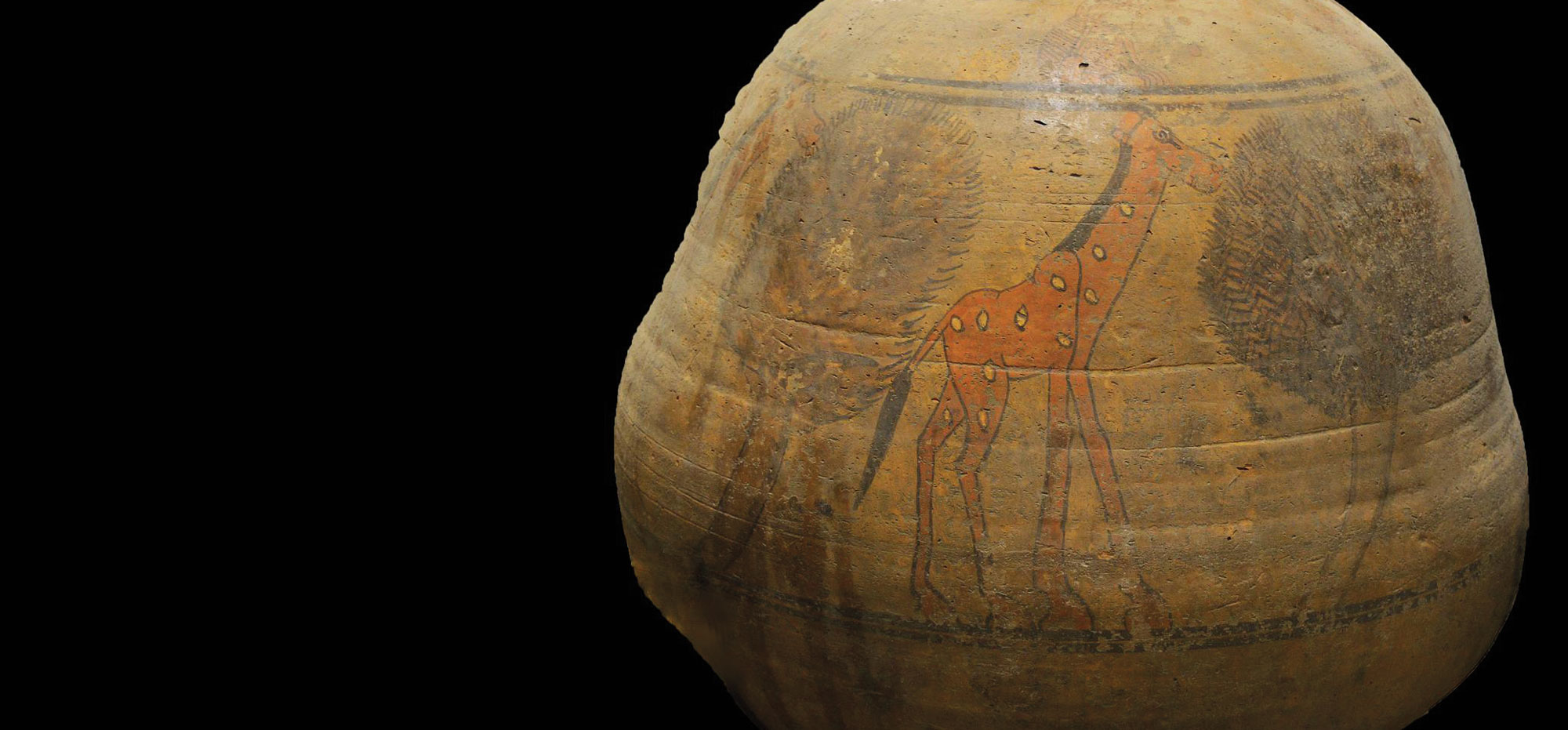

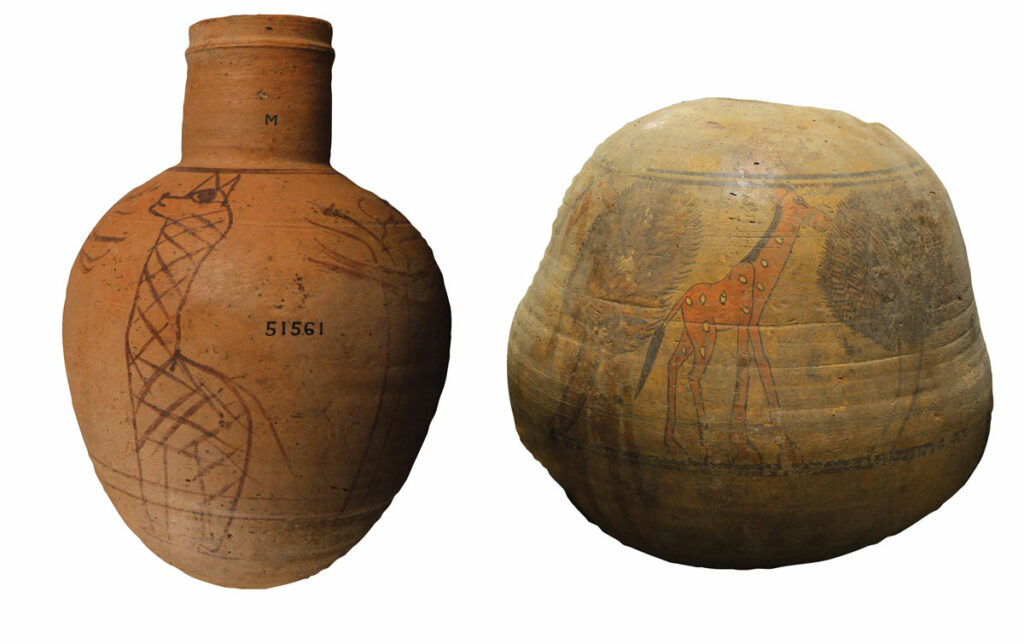

The world’s tallest mammals—and perhaps the most improbably proportioned animals on the planet—giraffes have always fascinated those lucky enough to see one. Archaeologist Loretta Kilroe of the British Museum has studied giraffe motifs in the art of ancient Egypt and Nubia (modern Sudan) and notes that depictions of the animals, along with their symbolic or spiritual importance, changed dramatically over time. During the millennium when the Kingdom of Kush held sway over most of Nubia, from around 790 B.C. to A.D. 350, giraffes did not appear in royal or public art such as temple reliefs. However, Kilroe has found that the creatures were commonly painted or incised on types of handmade domestic pottery generally assumed to have been made by women. “I think this is a window into an oral tradition in which giraffes were important to local people outside the officially sanctioned religious ideology,” she says.

In modern Sudan, giraffes are associated with solar imagery, and some scholars believe this may have been the case in ancient times as well, perhaps because their necks stretch toward the sun. Kilroe notes that, in the medieval period, Egyptian and Nubian depictions of giraffes on pottery were cruder, perhaps reflecting that, as the animals’ habitat shrank, fewer people had the opportunity to behold the wondrous beasts for themselves.