In some respects, the life of a Mesopotamian scholar in the seventh century B.C. was not so very different from that of a modern academic. While the former might be responsible for reporting on celestial phenomena and whether they augur well for the king’s reign, and the latter might be searching for evidence of a new subatomic particle to better understand the origins of the universe, in either case, one’s reputation among colleagues is paramount.

Let’s take, for example, the lot of an unnamed astrologer who was subjected to a vicious onslaught of peer review from some of the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s top minds after claiming to have sighted Venus around 669 B.C. In a letter to the king Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 B.C.), a fellow stargazer named Nabû-ahhe-eriba, who was part of the inner circle of royal scholars, inveighed, “(He who) wrote to the king, my lord, ‘The planet Venus is visible, it is visible (in the month Ad)ar,’ is a vile man, an ignoramus, a cheat!” Slightly more charitable, though still cutting, was a scholar named Balasî, who tutored the crown prince Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.). “(T)he man who wrote (thus) to the king, (my lord), is in ignorance,” Balasî informed Esarhaddon. “The ig(noramus)—who is he?…I repeat: He does not understand (the difference) between Mercury and Venus.”

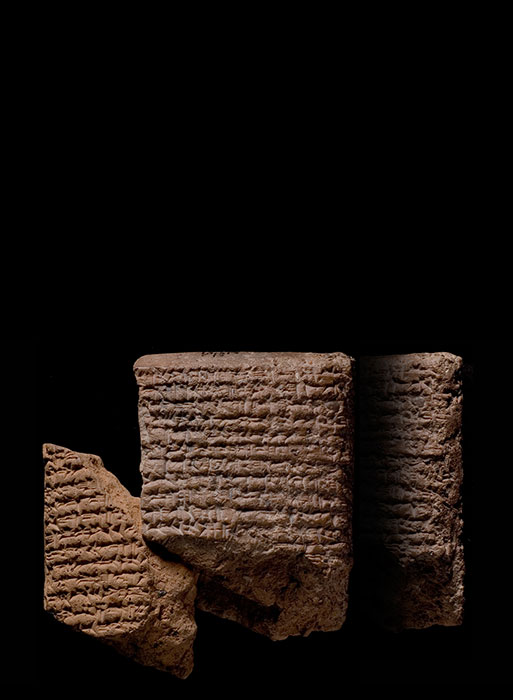

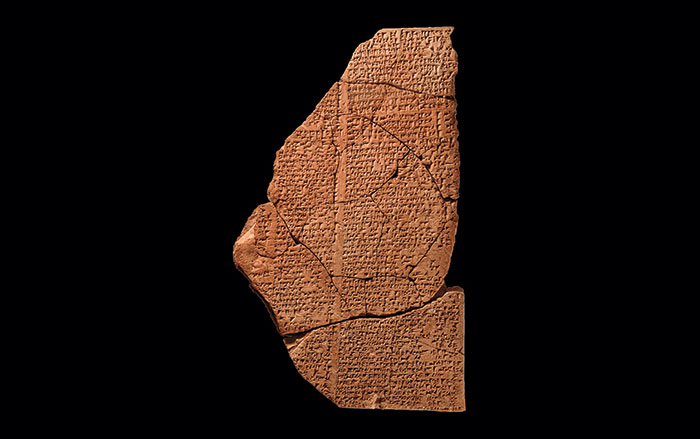

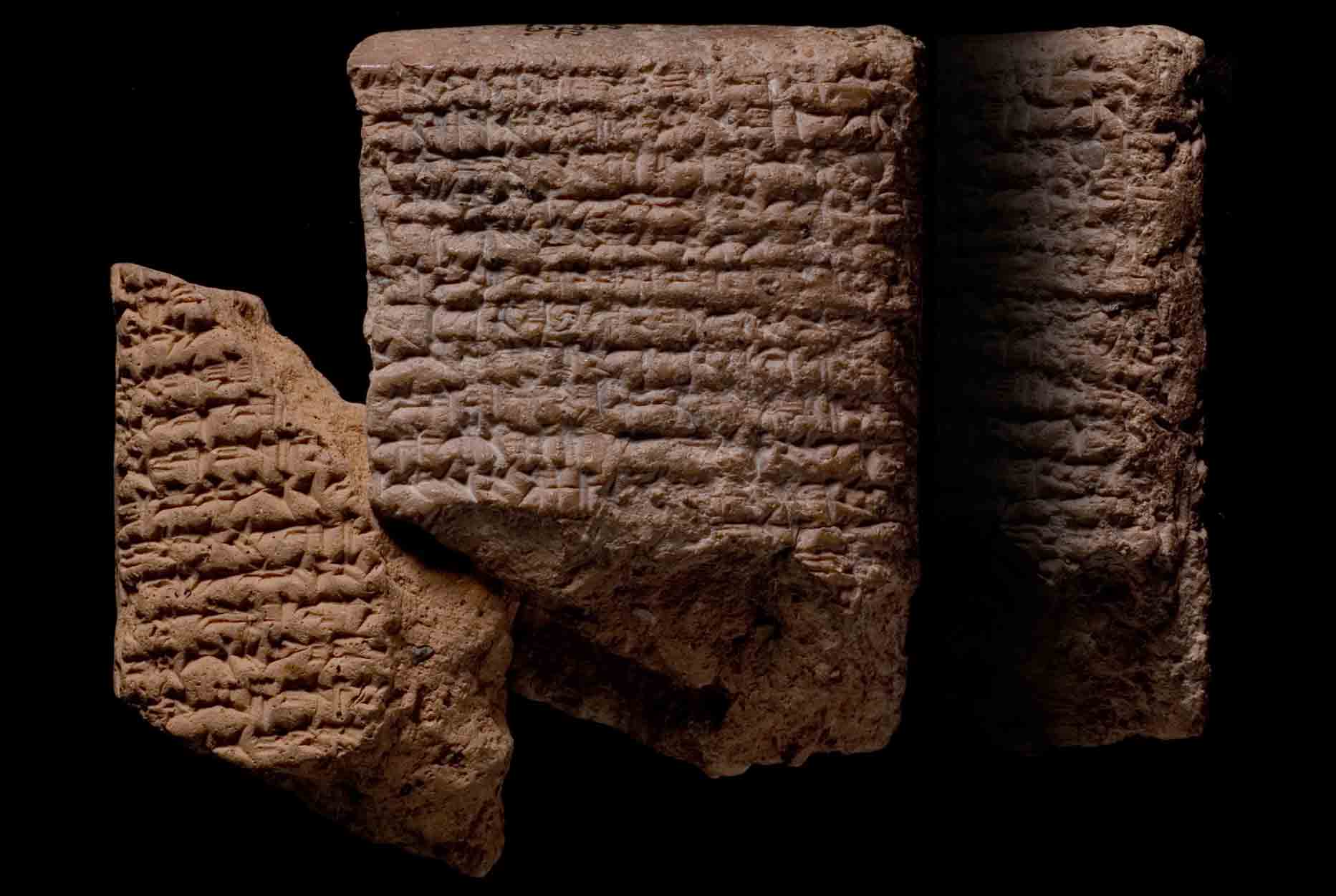

These quotations are excerpts from just two of around 1,000 letters and reports written by scholars to Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in cuneiform on clay tablets that were discovered during nineteenth-century excavations of the archives of the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, near Mosul in Iraq, including Ashurbanipal’s library. While researchers once viewed the ancient scholars as passive instruments of the king who lacked any independence, Assyriologists including Jennifer Singletary, until recently a researcher at the University of Gottingen, are now exploring how the letters illustrate both adversarial and friendly interactions among the scholars, as well as how scholars took distinctive approaches in their writing. “Assyriologists have tended to overemphasize the influence of the king and underemphasize the individuality of the scholars,” says Singletary. “I have been focusing more on the scholars’ relationships with one another and on how their interactions as colleagues and rivals influenced the writing they produced.”

When they weren’t excoriating fellow scholars they considered incompetent or deceitful, many ancient scholars collaborated with each other, frequently across city lines. This was particularly important when it came to astronomical observations, whose success could depend on the local weather. “Now there are clouds everywhere; we do not know whether the eclipse took place or not,” Bel-ušezib, a Babylonian scholar based in Nineveh, told Esarhaddon. “Let the lord of kings write to Assur and all the cities, to Babylon, to Nippur, to Uruk and Borsippa; maybe they observed it in these cities.”

Having connections to an extensive network of colleagues, particularly if they were widely geographically dispersed, could help a scholar find favor with the king. For instance, when a Babylonian astrologer named Marduk-šapik-zeri, who had fallen out of favor with Esarhaddon, tried to return to the king’s good graces, he cited not just his skill at observing good and bad portents in the sky, but also his connection to “twenty competent scholars worthy of royal desire.” These included a haruspex, or diviner, from Elam, in Iran, several exorcists from Assyria, and various other physicians and chanters.

Singletary points out that both Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal had good reason to encourage communication among scholars throughout the empire. Both kings were younger sons who were elevated to the throne over older brothers, causing intense controversy and strife during their respective reigns. Keeping tabs on omens discovered by a broad range of scholars was, therefore, highly advantageous. In Ashurbanipal’s case, he became king of Assyria while his older brother was named king of Babylon, a lesser yet competing position. “Ashurbanipal collected scholars almost the same way he collected tablets for his library,” says Singletary. “I wonder if his interest in making sure he was engaging with scholars in Babylonia as well as Assyria had to do with getting insider knowledge from his brother’s portion of the kingdom to make sure there weren’t any uprisings there.”