Located at the northwest edge of the Arabian Desert, the ancient city of Petra received less than four inches of rain each year. Nonetheless, in its heyday as the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom (first century B.C. to first century A.D.), the city thrived by carefully hoarding this meager rainfall and routing water from several natural springs in the surrounding hills. This required building a system of aqueducts, channels, bridges, and arches, and installing a network of pipelines. The system measured more than 30 miles in all and supplied the city with 35 million gallons of water per year. Petra’s extensive hydraulic infrastructure helped support a population of around 30,000. It also allowed for extravagant displays of conspicuous consumption designed to impress traders and dignitaries who made their way to the city, which was at the crossroads of caravan trade routes connecting Arabia and the Mediterranean.

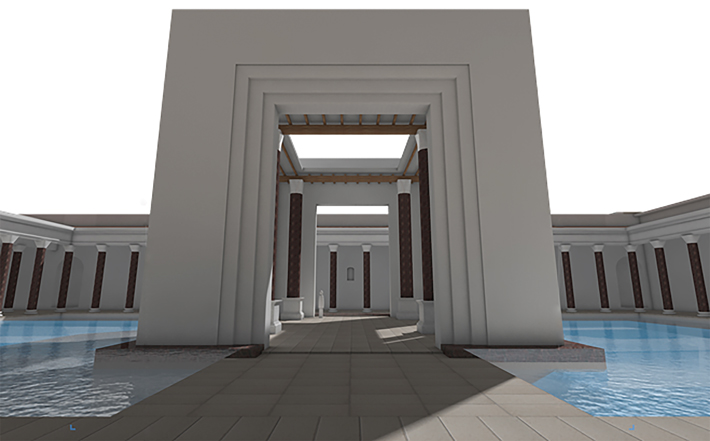

Among the most impressive of these projects was a monumental garden and pool that, since 1998, has been excavated by a team led by archaeologist Leigh-Ann Bedal of Penn State Erie, the Behrend College. On a terrace in the middle of the city that was once thought to have been the site of a marketplace, Bedal’s team uncovered evidence of the pool, which had been hewn from bedrock and measured 150 feet long by 75 feet wide and eight feet deep. In the middle was an island, 33 by 46 feet, outfitted with a pavilion decorated with imported marble and painted stucco. According to Bedal, the island would have been an ideal spot for banqueting or engaging in confidential conversations. “The pavilion had doors on all four sides, so you could see anyone coming,” she says. “You also had the sounds of water falling into the pool from the aqueduct above. So that would have added to the atmosphere and provided additional privacy.” The pool was built during the reign of the Nabataean king Aretas IV (reigned 9 B.C.–A.D. 40) and continued to be used after the Romans annexed Petra in A.D. 106. Within a century, though, the Romans had begun to neglect its upkeep, and the pool started to fill up with soil and debris such as pottery and animal bones.