A short trolley ride southwest from Philadelphia’s Center City, on a gentle curve in the Schuylkill River, lies a bucolic spread of land incongruously situated within a shabby urban neighborhood. In the shadow of an eclectic eighteenth-century Georgian-style stone house, there is a sprawling garden and, beyond, a meadow, rolling green hills, woods, mudflats, and wetlands. The urban skyline is distant but visible through clearings in the trees. In the spring, trillium, azaleas, and bottlebrush buckeye bloom, followed by evening primrose and passionflower in summer. Called Bartram’s Garden, it is the oldest surviving botanical garden in the United States, and was created in 1728 by John Bartram, a Quaker farmer and self-taught botanist who combed the eastern United States collecting plants and seeds. For a century, well-to-do Philadelphians traveled to Bartram’s Garden to buy orchids, peonies, and gardenias for their greenhouses and gardens, as well as cut blossoms for their homes. Bartram and his family operated the garden for decades and—without necessarily knowing it—spared thousands of years of history from being overrun by a spreading metropolis.

The 45-acre site, which is a National Historic Landmark as well as a park operated by the city and the nonprofit John Bartram Association, has had just a few owners—a French Huguenot, three generations of Bartrams, a railroad baron, and Philadelphia Parks and Recreation. It is as rich in history as it is in natural and landscaped beauty. Recently, in the depths of 2014’s cold, snowy winter, a crew of archaeologists from URS Corporation, a San Francisco–based company, were digging in an area of the site behind the house known as Carr Garden. They also recently completed a dig in a meadow down a winding path at the south end of the property. Modern Philadelphia has grown to nearly engulf this stretch of the Schuylkill River Valley. On three sides, Bartram’s Garden is hemmed in by industrial properties, public housing, and a railroad line, while across the river is a petroleum refinery and oil storage depot. But this piece of land has survived in part because of a history of caretakers who built lives here and preserved the land, and the record of its past, for future generations of stewards.

Joel Fry, the garden’s long-tenured curator and an expert on all things Bartram, had no hint that the land would reveal such a rich record of habitation—one stretching back thousands of years. “There is nothing like [what we discovered] anywhere else in Philadelphia,” says Matthew Harris, URS senior archaeologist and principal investigator, who has spent years excavating in urban Philadelphia and the Schuylkill River Valley, “for density of artifacts and the stories they tell.”

At the edge of the meadow, far from the house and primary gardens, at the southernmost property line, was a patch of wetland choked by invasive species, its flow to the tidal Schuylkill River blocked. This wetland was the reason the URS archaeologists dug in the meadow. Two miles downriver, the Philadelphia International Airport needed to expand a taxiway, and, to meet environmental requirements, it was required to compensate for the wetland it was consuming by rehabilitating another, according to Patricia Ann Quigley, an environmental consultant for the airport. The wetland enhancement plans originally included flooding part of the meadow, which required an archaeological assessment before the work could proceed. In 2012, the URS team opened 74 square-meter excavation units and dug one trench, all in less than an acre of the meadow. The site they uncovered was uncommonly deep. “We found 17,233 artifacts—new prehistoric information not available at other sites—going back maybe 5,000 years, and all the way up to deposits that tell us about the early Philadelphia park system, aspects of women’s and children’s lives, and the class divide,” says Harris. “We could see the artifacts in relation to each other, as they have been for centuries, undisturbed because the ground was never plowed under by agriculture.”

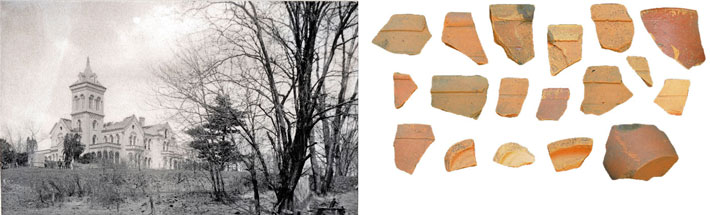

The deepest layers they uncovered turned up the biggest surprise: hearths, fire pits, and storage pits, situated throughout the meadow, up to a few feet from the water’s edge. They also found that the land had preserved the biggest assemblage of Native American artifacts ever found in Philadelphia. The ceramics they uncovered appear to come primarily from two periods: around 2500 B.C. and from A.D. 800 to 1200. Many of the early rim sherds they found bear “pseudo-cord” designs, which are made by twine impressions. “These are predecessors to more complex and refined geometric designs,” says Harris.

B.C., emerged from a meadow at Bartram’s Garden. " data-image-credit="(Courtesy URS Corporation, Photo: Matthew Harris)" srcset="https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-46.jpeg 710w, https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-46-300x278.jpeg 300w" sizes="(max-width: 710px) 100vw, 710px" />

B.C., emerged from a meadow at Bartram’s Garden. " data-image-credit="(Courtesy URS Corporation, Photo: Matthew Harris)" srcset="https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-46.jpeg 710w, https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-46-300x278.jpeg 300w" sizes="(max-width: 710px) 100vw, 710px" />Prior to these finds, there had been no surviving record of a Native American presence here, though the Lenape were known to have had villages at Passyunk across the river at one time, and called the Bartram site “Aronaneck.” Harris and Fry believe the finds, including expediently made stone tools, are evidence of centuries of seasonal use by hunter-gatherers. “Wild rice grew here,” says Harris. “They could have returned regularly for shad and other fish on spawning runs from the ocean, although we don’t have net and spear artifacts.” The investigators also did not find burials, postholes from a longhouse, or any other signs of permanent settlement.

It is not yet clear who from the tangled history of eastern Native American tribes were using the site. Lenape? Iroquois? Algonquin? “Debate goes on about who was where when,” says Fry. “But at [the time of European] contact some Lenape, Iroquois, and Algonquin had already intermingled. We do know that about a mile south of here the Swedes traded with Iroquois.”

When Fry mentions the “Swedes,” he is referring to a group of seventeenth-century colonists from Sweden, Finland, Germany, and elsewhere who collectively formed a short-lived colony called New Sweden (1638–1655). The Bartram’s Garden site lies on the northern edge of the colonial land, and from that group came the land’s next occupant: Andreas Souplis, a peripatetic Frenchman who settled down to farm and live there. Souplis, born in Alsace, was a Huguenot, one of a large group of French Protestants who were persecuted for their religious beliefs and driven from France in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Souplis moved to northern Germany and then sailed to the nascent Pennsylvania colony, where he helped settle Germantown and even became the town sheriff. In his very old age, he moved with his family to Aronaneck. The excavations at the site revealed the finery that Souplis brought with him. “We found ceramics, Staffordshire pottery, smoking pipes, a German Rhine Valley tankard top, a brass furniture pull,” says Harris. “High-quality stuff.” All the pieces date to between 1680 and 1720, which coincides with the time that Souplis lived there. “The coolest find was a redware piece, about 45 percent complete, in hand-executed sgraffito,” says Harris. “The only thing similar that I know of was found at Jamestown.” Sgraffito, a technique also used in illuminated manuscripts, involves layering one color over another and then scratching through the upper layer to create a decorative pattern. “It was clear that this was not a common dish, but more likely a cared-for and important possession,” Harris adds.

“Presumably there is more here,” says Fry. For example, any buildings constructed during Souplis’ tenure have not yet been located, and may lie underneath later structures. It would have been common to place new buildings on the sites, even on the exact footprints, of older ones. There were a few nineteenth-century structures on the property, and debris from them might conceal more Souplis material. Some of what we know of Souplis comes from the deed that transferred ownership of his land from his heirs to John Bartram, the man who gave the site both its name and its place in the history of American botany. Bartram’s explorations led him from Lake Ontario to Florida. He wrote books, sold specimens abroad, was chummy with Benjamin Franklin, was named King’s Botanist for North America by George III, and is still known as the father of American botany. His son William carried on this tradition, as did William’s niece Ann Bartram Carr and her husband Robert. All three generations tended and sold plants on the family property until 1850.

The Bartram house still stands and is open for guided tours. A greenhouse and barn remain as well. The meadow where so much Native American material was found did not provide any specific evidence of the Bartram ownership of the land. “We do know that John Bartram used this area for grazing his cattle,” says Harris. Bartram apparently did not grow crops on this spot. “It was never plowed under for agriculture, so that kept the artifacts in place.” The land also rarely floods, further preserving the archaeology below.

However, the preservation of the land itself and the use of acreage closer to the house as botanical gardens are certainly the results of the Bartrams’ presence there, and are evidence of their role in the land’s stewardship. Ann Bartram Carr made an area close to the house, Carr Garden, her own showplace of exotic species, with 300 varieties of dahlias around boxwood-lined pathways. In early 2014, the URS archaeologists opened 13 units there, a total of 200 square feet, to help the John Bartram Association in its plans to reconstruct the garden with as much historical accuracy as possible. Extant plans and some early photographs helped guide the archaeologists and showed several paths through the garden, leading to the house and a nearby orchard. “We found the path in five different units,” says Harris. “We confirmed its presence, depth, arc, and construction material. And we found planting beds associated with the path in three units.”

Among other surprises—including a number of prehistoric artifacts up to 4,500 years old—Harris found pre-Carr-period soils, likely from the time of her uncle or grandfather. “The key information for us from the archaeology will be placement and path alignment,” says Brad Thornton, an associate with LRSLA Studio, the landscape architecture firm at work on the project. “To be practical, for durability we will have to use new materials [on path surfaces] and re-create a look that is historically authentic.” Rounding up the historical plants, however, will be difficult because so many have fallen out of fashion.

Indeed, changing fashion in the gardening world may have been the reason that the Bartram family sold the property in 1850 to Andrew Eastwick, who clearly saw the value in the Bartrams’ use of the land as a botanical treasury. Eastwick was born in Philadelphia (a nearby neighborhood is named after him) but made his fortune building locomotives in St. Petersburg, Russia. He retired to Bartram’s Garden and built an Italianate mansion atop a hill overlooking the Schuylkill, leaving the Bartram house and garden intact. Evidence of Eastwick’s time on the property appeared in the meadow, where the archaeologists located and examined the foundations of his greenhouse—full of broken flowerpots—and another building next door. According to records, this was an engine house, which, in retrospect, provides a connection between the greenery of the park and garden and the industrial sites that line the rest of the Schuylkill. “These buildings were side by side. And one had a floor to support something big,” says Harris. “Was it some kind of workshop where he developed his engineering ideas? I’m in love with the idea of finding his St. Petersburg prototype, but it was probably how he heated his house, with a duct running in between. We did find one-inch and three-inch pipes coming from the engine room. Still, that’s cool, from a technological standpoint. Who has a tunnel leading to his house for heat?”

Consciously or not, Souplis, Eastwick, and Bartram were extraordinary stewards of this land, even as urban Philadelphia approached. Following Eastwick’s death in 1879, industry and urban expansion threatened to finally overwhelm Bartram’s Garden. A campaign to preserve it—in the spirit of Bartram and his gardening traditions—was undertaken and ownership of the site was granted to the city in 1891. With that, the role of steward passed to Philadelphia Parks and Recreation, which created a public park on the property.

Eastwick’s mansion burned down in 1896, so the city razed it and filled the site in. They put an ice rink where the wetlands are today, and by the turn of the twentieth century, streetcars ran to the neighborhood, called Kingsessing (another Lenape word). Upper-middle-class Philadelphians, especially mothers and children, socialized and engaged in genteel pastimes, and evidence of this period surfaced in the excavations of the meadow, which would have been next to the skating rink. “We found lots of tea cups and service sets, jewelry, ladies’ brooches, and child-size rings and bracelets. And a fancy pocketknife, jacks, marbles, and lots of toys,” says Harris. In one cluster, the archaeologists found the remains of a picnic—a tureen, a mustard jar, and an olive container.

Other artifacts from this period suggest a different side of early-twentieth-century life. In one area, out of sight of the main house, the excavators uncovered a large number of milk bottles. Fry and Harris theorize these may have come from a Hooverville, one of the emblematic shantytowns of the Great Depression, not unlike the one that appeared in the middle of New York’s Central Park. In a twist, the milk bottles came from Suplee-Wills-Jones dairy—and the Suplees are the descendants of Souplis, the original landowner.

In light of all the finds made in the meadow and around the property, engineers from URS curtailed and rejiggered the wetlands mitigation project so that the meadow has not been flooded. And this is what preservation today requires, something that Bartram and the other owners probably never would have thought to consider: accounting for the site’s natural history as well as its human history.