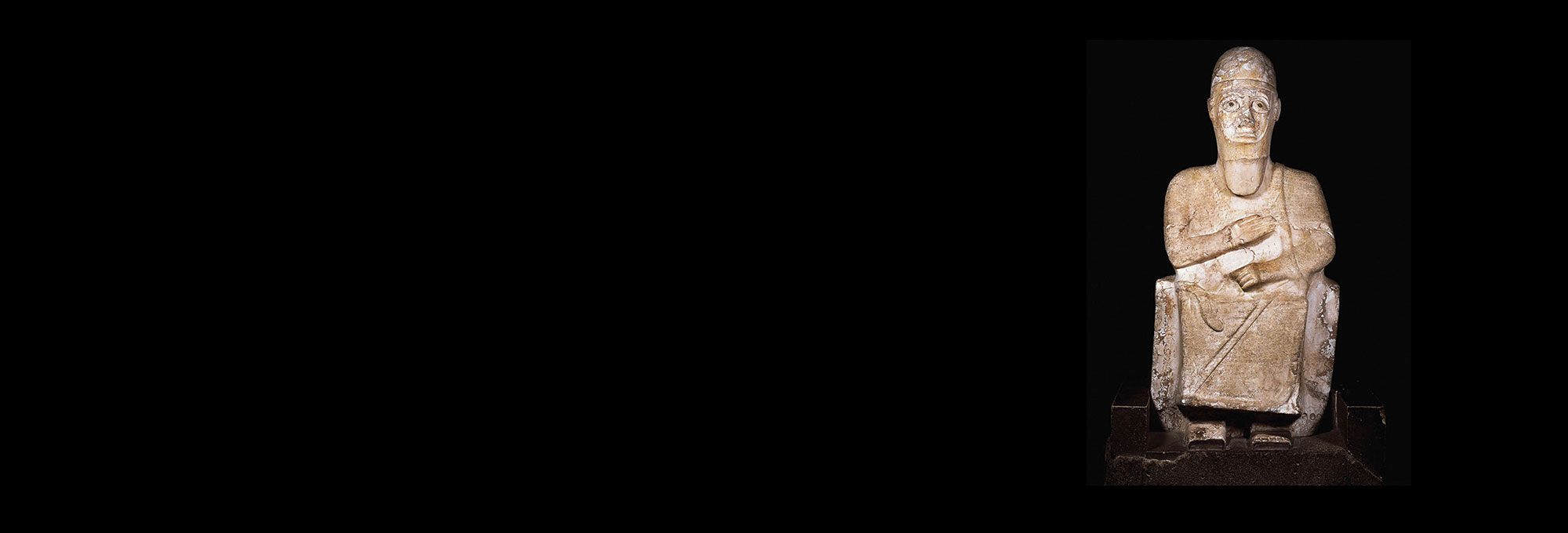

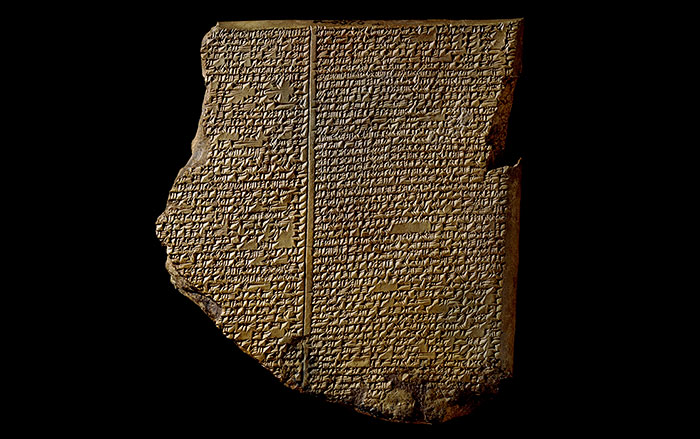

Royal inscriptions are among the most important sources of ancient Near Eastern history. One of the most intriguing examples is found on the statue of King Idrimi, who ruled Alalakh, a city in present-day Turkey, in the fifteenth century B.C. A lengthy cuneiform inscription sprawls across the statue, spinning a first-person tale of exile, triumph, and redemption.

“In Aleppo, the house of my father,” it begins, “a bad thing occurred, so we fled to the Emarites, my mother’s kin.” Idrimi, a younger son unwilling to play a diminished role, decamps for Canaan, where he finds countrymen who recognize his royal lineage. With their help, he wins over his home city and is proclaimed its rightful ruler by the king of Mitanni, the major regional power. Idrimi then repairs Alalakh’s toppled city wall, conquers more cities, builds a palace, cares for his people, and performs the necessary prayers and sacrifices.

The portion of the inscription that covers Idrimi’s reign is very similar to inscriptions left behind by kings from across the ancient Near East, from Hammurabi of Babylonia (r. 1792–1750 B.C.) to Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria (r. 883–859 B.C.). “The things Idrimi does once he becomes king are the things that Near Eastern kings conventionally claimed to have done in their inscriptions,” says Jacob Lauinger, an Assyriologist at Johns Hopkins University. However, Lauinger adds, the portion covering Idrimi’s exile is more akin to the Old Testament stories of Joseph and David, both younger sons who reach great heights. Just as the inscription’s narrative is a hybrid, so is its language. It is written in Akkadian cuneiform—as was only proper for a royal inscription at the time—but with clear Canaanite influences, such as the placement of verbs at the beginning of clauses.

Although the text reads as if written by Idrimi during his reign, a recent reanalysis of the statue’s stratigraphy suggests it may actually have been written several decades later. As scholars continue to puzzle over this most unusual royal inscription, the wish expressed in its final lines has been fulfilled: “I wrote my service down on my tablet. May one regularly look upon them [the words] so that they [the words] may call blessings on me regularly.”