During the millennia in which cuneiform script was used, Mesopotamia saw city-states jockey for resources, empires grow and dissipate, and seemingly countless kings made and unmade on the battlefield. Successful military campaigns brought land and resources, affirmed royal power, and granted privileged access to the gods. In turn, sculptures, reliefs, and cuneiform writings were commissioned to memorialize victories and legitimize claims. The Stela of the Vultures documents one of these conflicts from Sumer’s Early Dynastic III period (2600–2350 B.C.). “The monument stands at the beginning of a long line of historical narratives in the history of art,” says Irene J. Winter, a professor emeritus at Harvard University, in her analysis of the stela.

During this period, Sumer was a collection of city-states surrounded by agricultural land. As the city-states grew, so did the potential for border conflicts, such as one that raged for 200 years between Lagash and Umma, both in present-day Iraq. The Stela of the Vultures, which survives as seven fragments of what was once a six-foot slab of limestone, records Lagash’s eventual victory. One side depicts the god Ningirsu, holding his enemies in a sack, while the other shows a series of scenes from the conflict. A cuneiform account by Lagash’s leader, Eannatum, wraps around the stela: “Eannatum struck at Umma,” it reads. “The bodies were soon 3,600 in number....I, Eannatum, like a fierce storm wind, I unleashed the tempest!”

The historical side depicts Eannatum leading a phalanx of soldiers trampling enemies underfoot, a victory parade, a funeral ceremony, and another, poorly preserved tableau—along with, at top, the image that gives the stela its name, a kettle of vultures consuming the heads of Umma soldiers. It is, in a way, a document both poetic and legal—it invokes the grace and power of Ningirsu, and stakes a claim to land won by force.

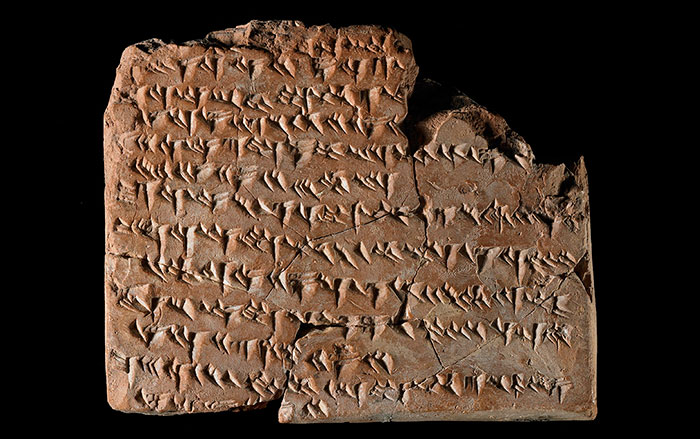

Lagash’s primacy was short-lived. By the end of the period, Umma had plundered its rival and begun the consolidation of power that would result in the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The tradition of documenting battles in words and pictures continued, perhaps reaching a peak with the Assyrians in the seventh century B.C., when they carved elaborate battle reliefs in the North Palace of Nineveh in present-day Iraq, and documented the siege of Jerusalem on a series of octagonal clay prisms called Sennacherib’s Annals.