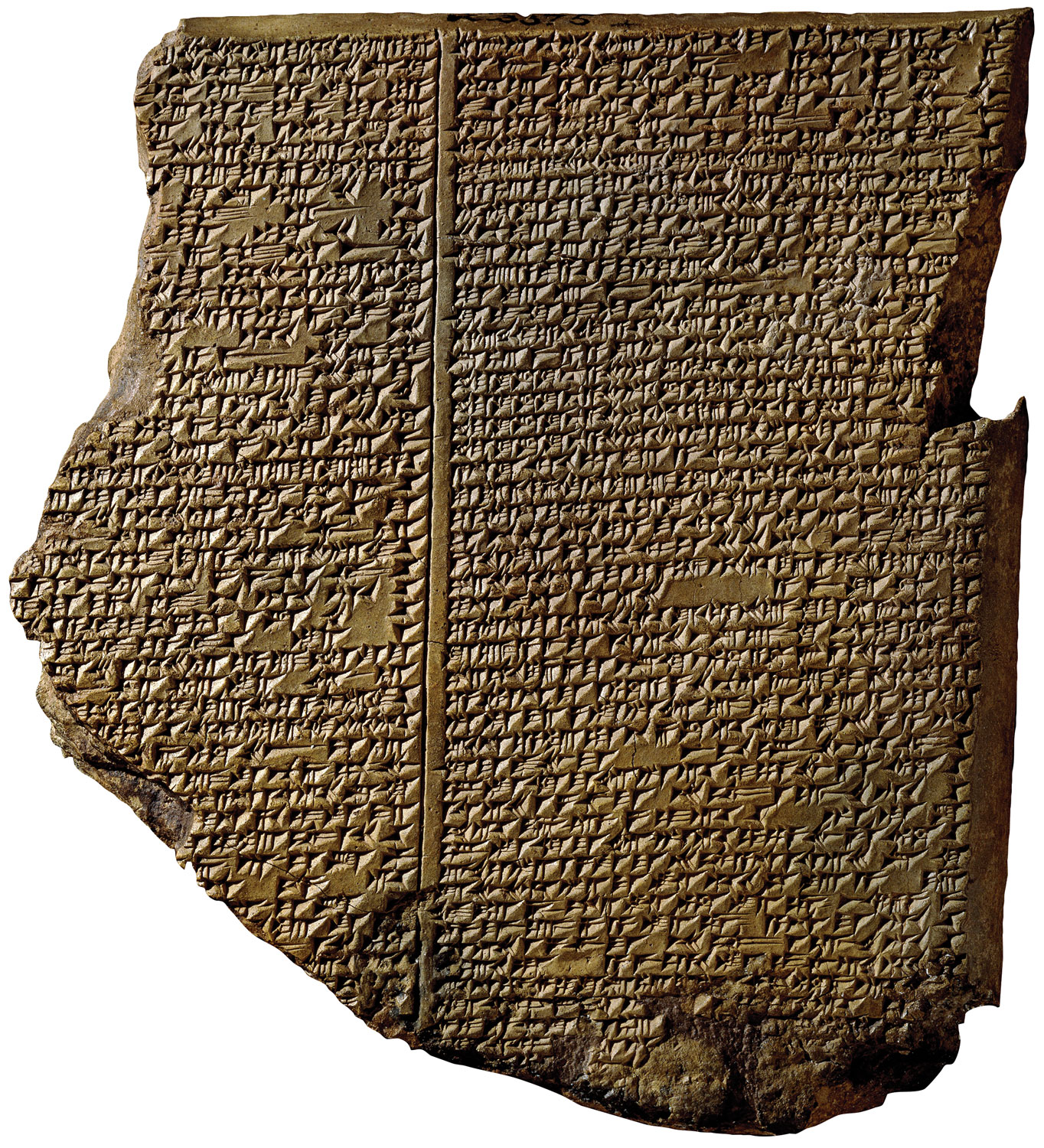

In November 1872, a self-taught Assyriologist named George Smith working as an assistant at the British Museum happened upon a fragment of a tablet that would soon become the most famous cuneiform text in the world. One of thousands excavated decades earlier at Nineveh, in present-day Iraq, the tablet told a story eerily similar to that of Noah in the Old Testament. In it, the gods resolve to destroy the world and all life with a great flood, but one of the chief gods warns one man in time to prevent the extinction of all living things: “Demolish the house, build a boat!” the god urges. “Abandon riches and seek survival! Spurn property and save life! Put on board the boat the seed of all living creatures!”

The man, his family, and assorted animals wait out the flood in the boat while all other living things perish. Smith presented his translation several weeks later at the Society of Biblical Archaeology to a packed audience that included the prime minister, the archbishop of Canterbury, and many members of the press. “When Smith announced that one of these unappetizing-looking tablets from the barbaric, strange world of the Middle East contained a parallel text to Holy Writ, people were astonished,” says Irving Finkel, a cuneiform expert at the British Museum.

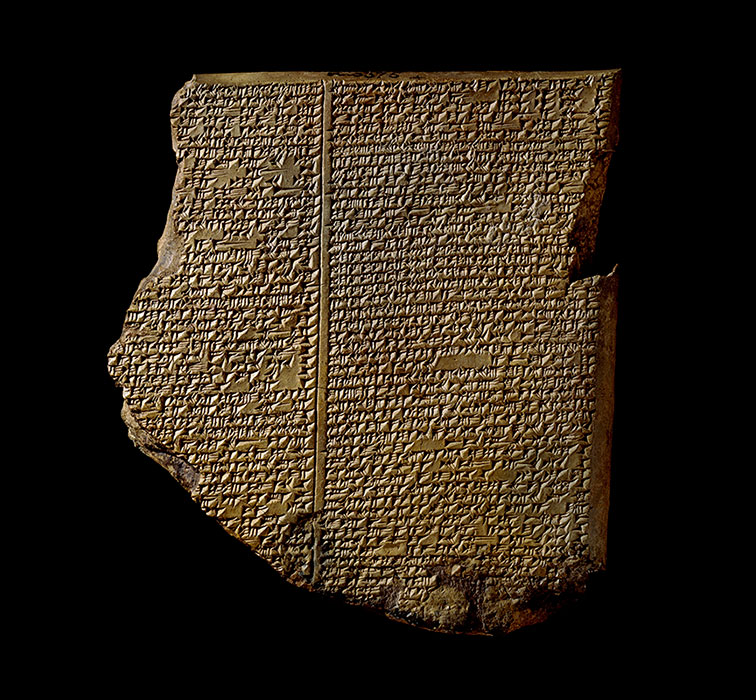

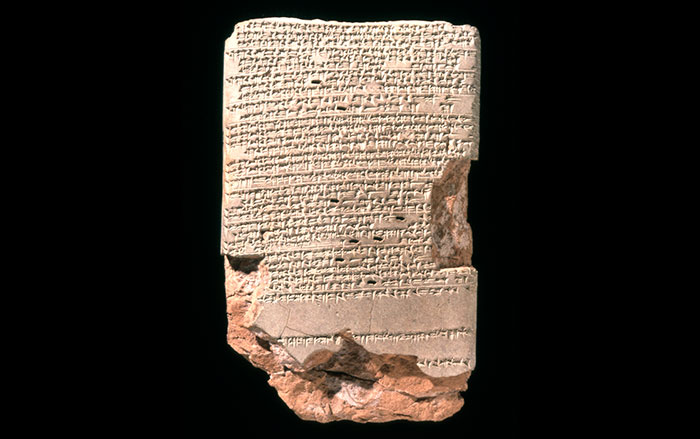

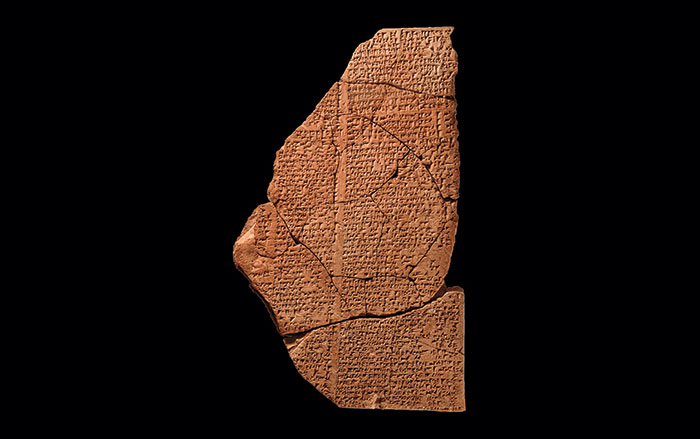

The tablet deciphered by Smith turned out to be the 11th part of the 12-tablet Epic of Gilgamesh and had belonged to the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.), who aspired to gather all known cuneiform writings. Since Smith’s discovery, more than a dozen cuneiform tablets containing some portion of the flood myth have been identified, the earliest of which predate the earliest known versions of the biblical flood text by a thousand years.