When Christopher Donnan began studying the art created by Peru’s Moche culture more than 50 years ago, he wasn’t sure how much it reflected ancient reality. From about A.D. 200 to 850, the Moche lived in the arid valleys of Peru’s northern coast, where they practiced intensive irrigation agriculture and built vast ceremonial complexes. Moche artists created murals and decorated pottery with vivid images of fantastic rituals featuring participants who were part animal and part human. They also painted scenes of figures, some wearing elaborate clothing that indicated their elite status, engaged in a mysterious spear-throwing activity scholars dubbed “ceremonial badminton” due to the use of a feathered object that looks somewhat like a shuttlecock.

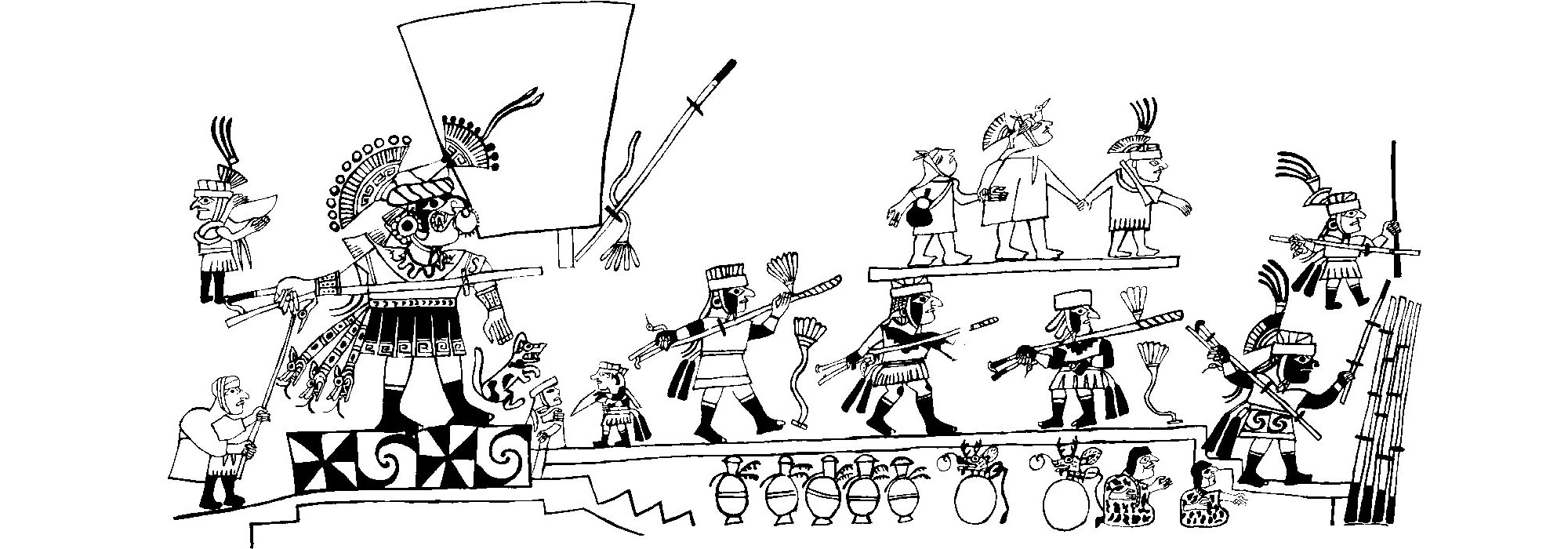

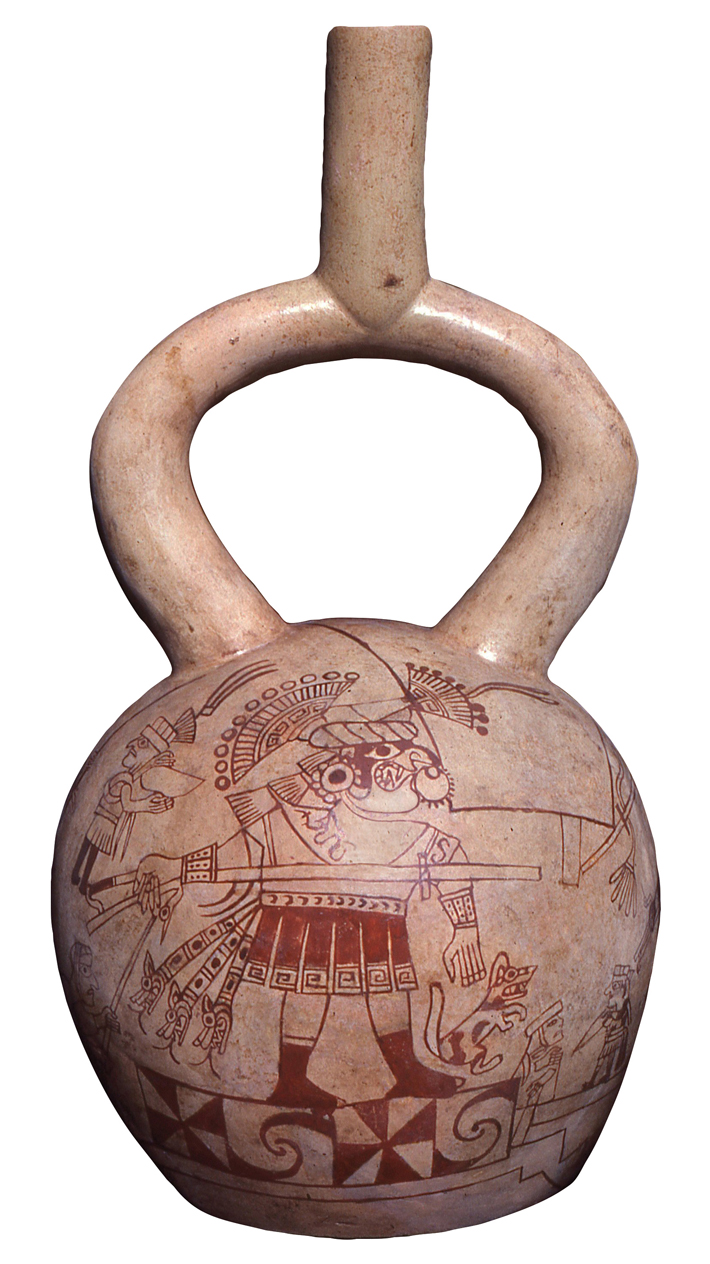

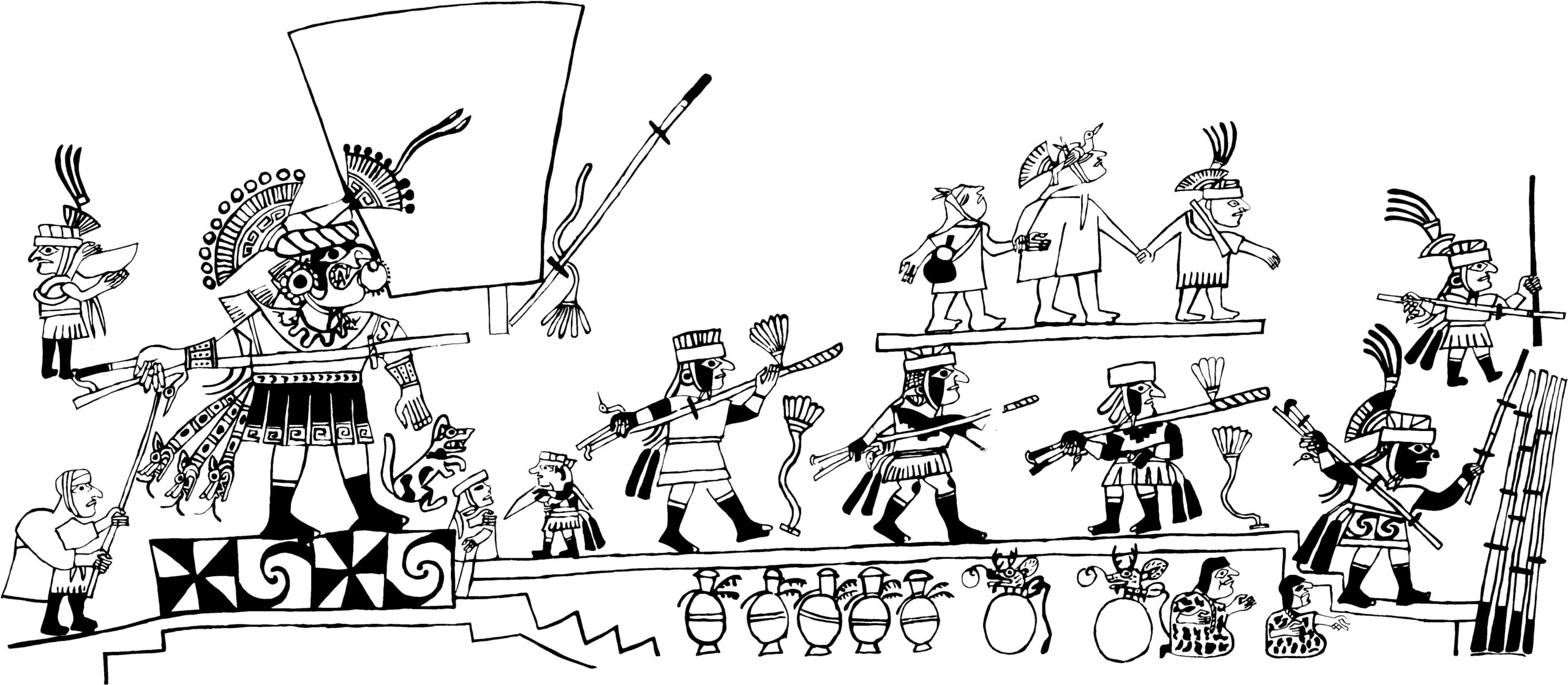

Early in his career, Donnan wondered whether the images might depict mythical figures operating on a supernatural plane rather than real people enacting ceremonies on Earth. The rituals certainly seemed to stretch the limits of reality. Chief among them was the sacrifice ceremony, in which attendants slit prisoners’ throats and collected their blood in goblets, which were then presented to the presiding priest. The beings participating in the sacrifice ceremony took human form, but had body parts such as fangs, jaguar heads, and bird beaks. There were also depictions of ceremonial badminton contests that showed groups of figures armed with a type of spear-thrower called an atlatl, which is essentially a stick with a handle on one end and a hook or socket that attaches to a spear on the other. Participants seemed to use their atlatls to hurl spears with feathered objects attached to them. Like the sacrifice ceremony, ceremonial badminton could have been an actual event or a supernatural contest that occurred largely in the Moche mythological realm. “When I looked at these rituals I often wondered if the activities were real. Did they really do that?” says Donnan.

Now, building on decades of archaeological discoveries and his own extensive experience analyzing depictions of Moche rituals, Donnan, an archaeologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, has re-created ceremonial badminton. In bringing to life a contest that for more than 1,000 years was confined to painted scenes on ancient pottery, he has been able to get a glimpse into the lived experience of the Moche that artifacts rarely afford.

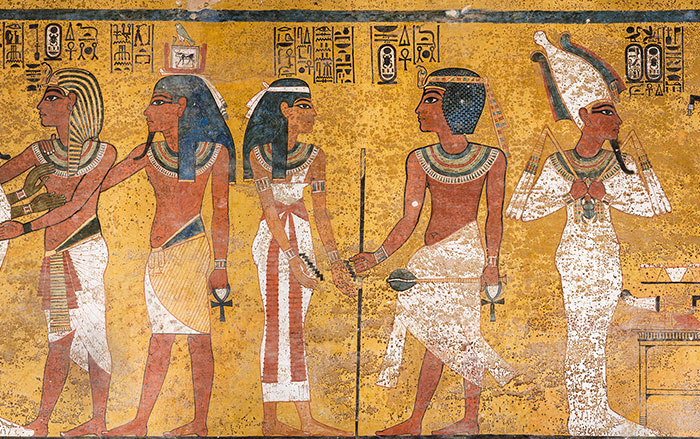

The question of whether or not Moche art depicts real events was settled in 1987, when Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva excavated the tomb of a Moche nobleman now known as the Lord of Sipan. This nobleman had been buried in northern Peru’s Lambayeque Valley along with the bodies of six attendants. The lord wore an elaborate costume that closely resembled the artistic representations of the sacrifice ceremony’s participants. In a nearby tomb, archaeologists discovered the burial of a man who wore a large owl headdress that mimicked how a figure known as the Bird Priest appears in Moche art. Alva and his team even found goblets that had once held the victims’ blood. “That really changed everything,” recalls Donnan, who analyzed Alva’s discoveries and confirmed their parallels to the art he knew so well. “This made clear that what you see in Moche art is real.”

As archaeologists uncovered more and more evidence for these sacrifices, including the dismembered bodies of victims at a site called Huacas de Moche, or “Pyramids at Moche”—as well as the ceremonial use of hallucinogenic drugs, as evidenced by images of a local cactus that contains mescaline—the reputation of this ancient culture that Donnan so loved began to harden in ways he found disturbing. “It isn’t as though this was everything the Moche did,” he says, “but when they are portrayed, it’s sex, drugs, and violence.” Still, since he knew that the art accurately depicted the Moche sacrifice ceremony, Donnan had to concede the event was probably a serious and brutal affair.

Donnan went on to excavate other Moche tombs, including one at the site of San Jose de Moro that held the body of a priestess whose garb matched that of a female participant sometimes depicted in the sacrifice ceremony. He unearthed another tomb at Dos Cabezas, or “Two Heads,” that was filled with prestige goods such as gold and silver nose ornaments, decorated ceramics, and a naturalistic burial mask made of copper and shell. Throughout his career Donnan remained fascinated by Moche art, and he found himself increasingly interested in the depictions of ceremonial badminton.

In these scenes, the activity’s basic form seemed clear. One person used an atlatl to toss a spear with the feathered “shuttlecock” tied to it into the air. The feathered object seemed to unwind from the spear in mid-flight and float toward the ground. Several other people stood nearby at the ready holding atlatls and spears outfitted with crosspieces—generally two pieces of wood in the form of an X attached to a spear shaft. The goal of the ritual appeared to be to toss the spears with crosspieces at the feathered object, trying to snare it before it reached the ground.

Donnan easily recognized the game in Moche art, but he found it difficult to picture anyone actually playing it. The mechanics seemed a bit questionable: Would the string attaching the feathered object to the first tossed spear really unspool perfectly in midair? Wouldn’t it be impossibly hard to catch the shuttlecock on its way down? But given everything he had learned about Moche art faithfully depicting the sacrifice ceremony, he reasoned that ceremonial badminton must have also once been a feature of Moche religious life. One day in 2014, after decades of studying drawings of the ritual, Donnan decided to finally give Moche badminton a try. He and a friend fashioned makeshift spears and atlatls out of PVC pipe. They attached a small, light piece of wood with feathers tied to it to one of the spears with a string. They then tossed the spear into the air. “This was really a lark,” Donnan says. Yet even with their makeshift equipment, standing in the street outside Donnan’s Los Angeles home, it worked perfectly. “The string unwound in the air exactly the way it’s depicted, and the feathered object floated down slowly,” he says. “It was uncanny.” Aware that he was just a beginner at spear-throwing, Donnan wondered how much more could be learned about the ritual if it were performed by people who actually knew how to use atlatls.

After doing some research, Donnan found that there were many groups of atlatl enthusiasts, mostly in the United States and Europe, who fashioned their own atlatls, practiced throwing spears with them, and even held competitions. He decided to contact Chris Henry, an artist and experimental archaeologist, to propose the idea of re-creating ceremonial badminton. “I thought, ‘He will read this email and just think I’m a quack,’” Donnan says. But within 10 minutes, Henry had written back and was eager to get started. Henry, who runs a company called Paleoarts that specializes in creating functional replicas of prehistoric tools, has had a lifelong fascination with ancient technology—and he particularly loves the atlatl. Henry notes that a simple flick of an atlatl can propel a spear with 200 times more force than the human arm can muster, and with much greater accuracy. “It’s the great unsung invention of humankind,” he says. Paleolithic stone points that seem to belong to spears hurled by atlatls have been found in Africa and suggest the spear-thrower may have first been developed as early as 150,000 years ago. Fragments of atlatls carved from mammoth ivory that date to around 17,000 to 15,000 years ago have been discovered in Europe. Atlatls eventually spread throughout most of the world, before being largely replaced by the bow and arrow. Some communities, including duck hunters living around Mexico’s Lake Patzcuaro and Inuit groups that hunt seals in the Artic, continue to use atlatls to this day.

Every person who ever used an atlatl for hunting or warfare probably also used it for target practice, and many likely took advantage of the opportunity to show off their skills or compete for status. For the Moche, ceremonial badminton may have served as both target practice and as a form of competition, perhaps not unlike the tournaments that bring together modern-day atlatl enthusiasts. When Henry saw Moche depictions of the shuttlecocks and crosspieces used in the ancient game, he says, “I immediately knew what was going on, and I thought, ‘Oh yeah. I can make those.’”

After a few months of work creating and experimenting with replicas, Donnan and Henry took their ceremonial badminton equipment to the World Atlatl Association’s annual gathering in the Nevada desert in the spring of 2015. Between Donnan’s knowledge of the game and Henry and his fellow atlatlists’ agility with spear-throwers, they quickly worked out the kinks. “It caught on instantly,” Henry says. Most of today’s atlatl sports are individual events, similar in spirit to archery or javelin throwing. This new version of ceremonial badminton, on the other hand, could be played in groups, and it wasn’t a competition per se. Rather, one or two people launched the spears equipped with shuttlecocks—which Henry had made out of wine bottle corks—and everyone else in the group tried to bring them down. No one kept score, and there were no teams.

That day in the desert, as Donnan watched the atlatl hobbyists scramble to snare the shuttlecocks, laughing when they missed and celebrating when they succeeded—which happened far more often than he expected—he realized something that had never occurred to him before. Ceremonial badminton, so long associated with the solemnity of Moche religion, could actually be fun. “To me it’s very human,” says David Anderson, an archaeologist at Radford University in Virginia who studies ancient sports such as the ritual ball game played throughout Mesoamerica. “This is target practice. This is something people have always wanted to do, all over the world, and we still do it today.” Anderson says that ceremonial badminton was likely taken very seriously by its participants and spectators and certainly had a religious significance. He points out that the Moche could perform important rituals and enjoy athletic contests at the same time. He emphasizes that athletes and fans still participate in rituals related to sports today, from baseball superstitions to tailgate parties. “We mystify that for other cultures, and we presume it’s normal for our own,” he says.

Before helping to re-create ceremonial badminton, Donnan had always thought of Moche ceremonies as somber affairs that were enacted as discrete events. “Now, I have an entirely different perception of activities we see depicted in Moche art,” he says. He believes there were Moche festivals, where ceremonial badminton was performed alongside other rituals such as human sacrifice, accompanied by music, drinking, and feasting—somewhat like the ancient Greek Olympics, a festival that also included a wide variety of religious as well as athletic events.

Donnan still doesn’t know what the precise rules of ceremonial badminton were, or how players won or lost. He doesn’t know what the activity meant or represented in the context of Moche festivals, and he’s not sure that he ever will. One way to learn more about ancient ceremonial badminton, Donnan says, would be to find the tomb of a player buried with the game’s equipment, just as the Lord of Sipan was entombed with the trappings of the sacrifice ceremony. But the ancient game’s rules are likely lost, so it’s up to modern players to create their own. Because Henry and his fellow spear-throwers are sure of one thing: Ceremonial badminton is too much fun to let it disappear again. Now dubbed the “Moche toss,” it’s played by atlatlists across the world.

Video: Playing Moche Badminton

This video was shot at the Valley of Fire State Park in Nevada and shows a group of ancient technology enthusiasts playing Moche toss, a game based on the reconstruction of an ancient Peruvian ritual activity known as Moche ceremonial badminton. The video was produced and edited by University of Colorado Boulder archaeologist Devin Pettigrew. To learn more about the equipment the players are using, visit Pettigrew's website Basketmakeratlatl.com.