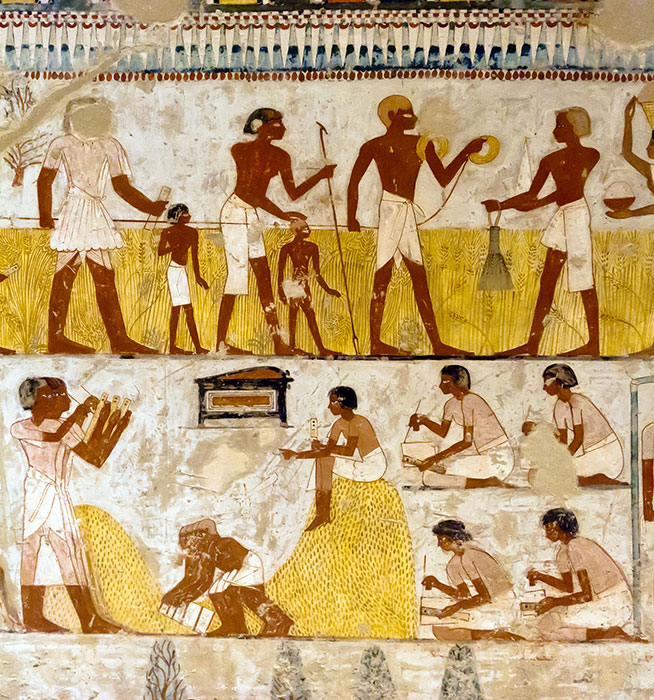

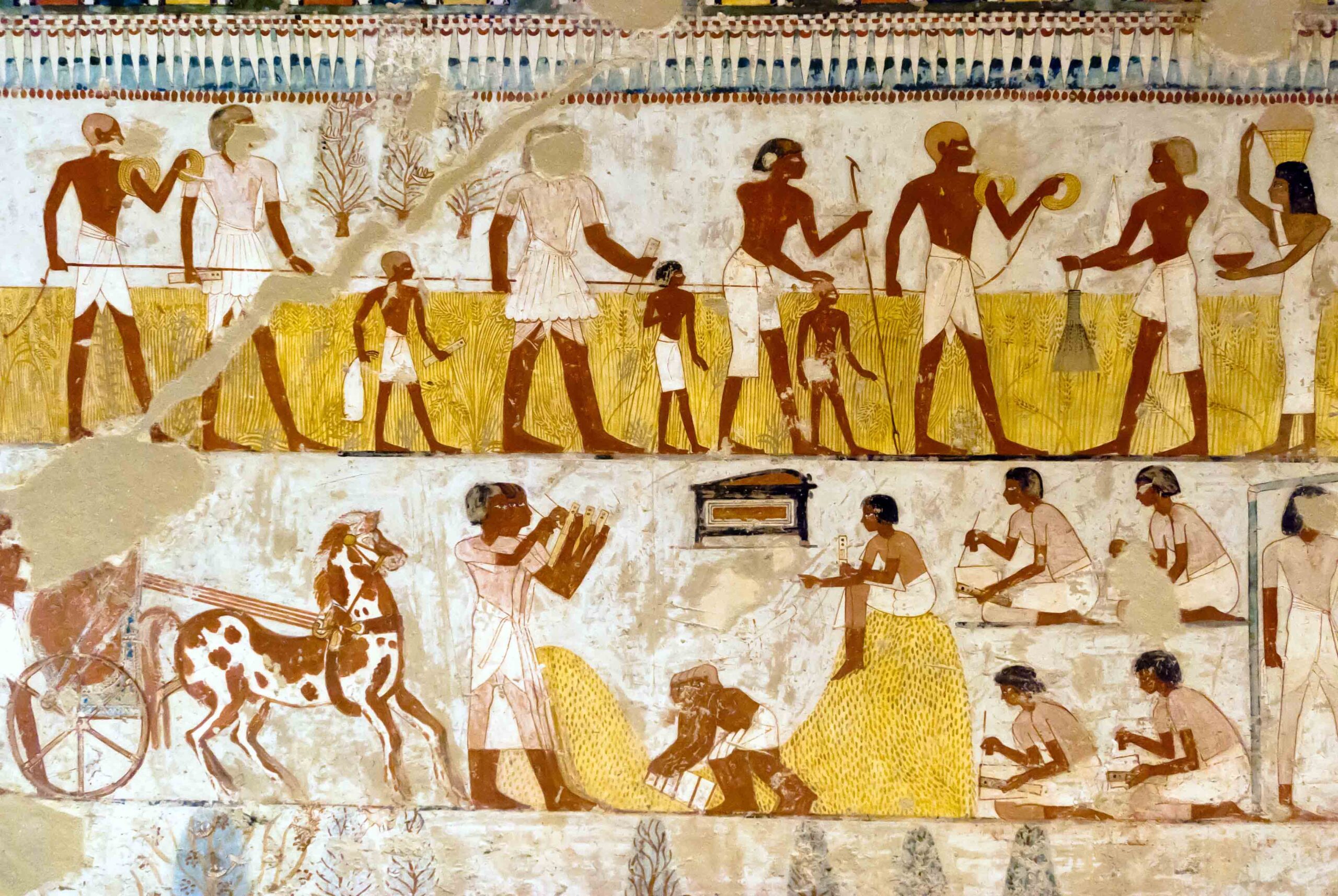

Throughout ancient Egyptian history, taxes were very much part of daily life. Most Egyptians were farmers who owed the state both a period of labor service and a portion of their annual harvest. The pharaohs of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.) levied these taxes on villages and towns collectively. When communities failed to fulfill their tax quotas, their administrators were held accountable. “The penalties could be quite severe,” says University of Chicago Egyptologist Brian Muhs. “We have depictions in mortuary chapels of town chiefs being beaten in front of scribes for failing to pay taxes.”

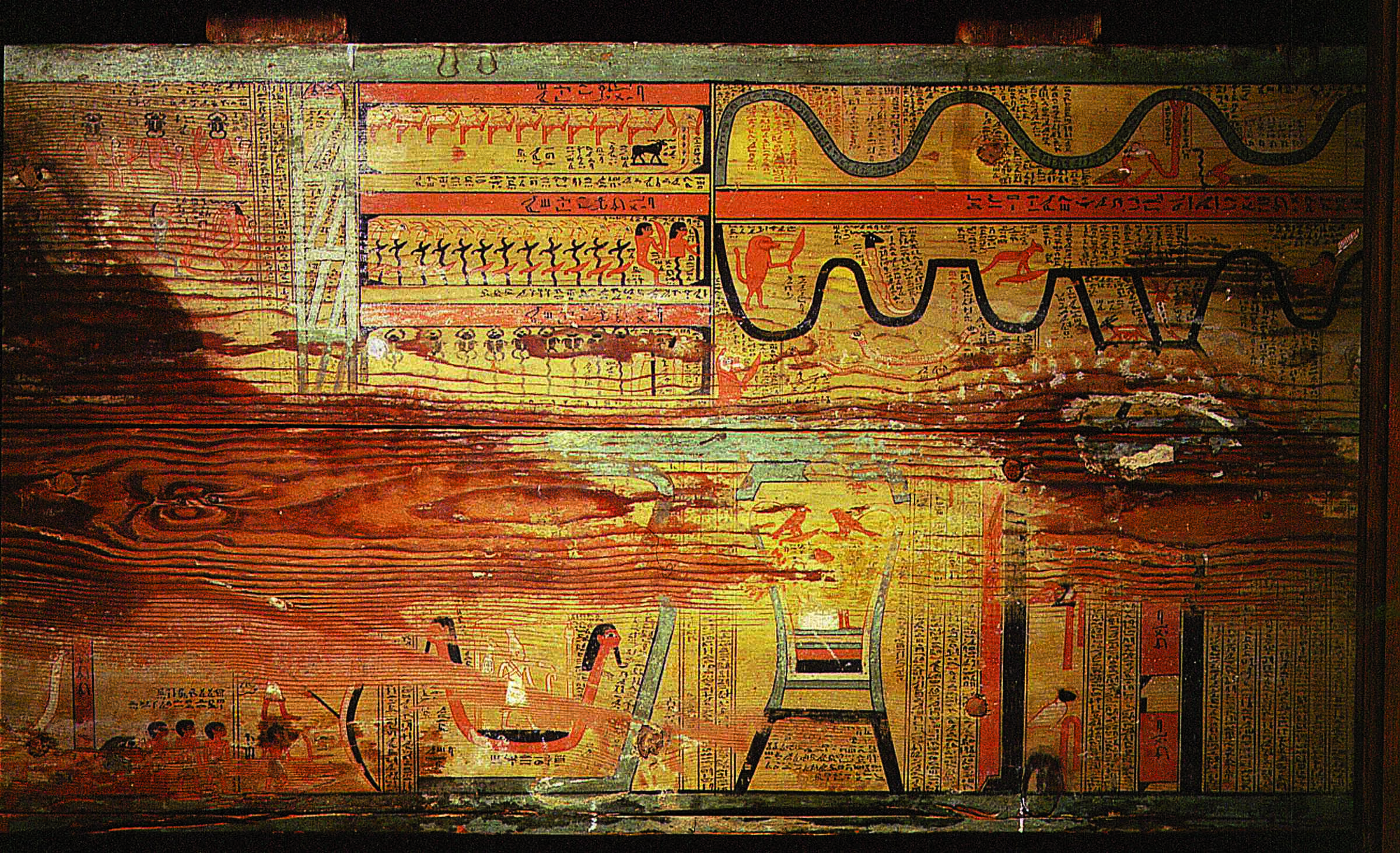

Muhs points out that it was probably a great relief to these local administrators that during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), the Egyptian state began to tax individual people and fields, rather than communities. This was only possible due to the exponential growth in the number and abilities of Middle Kingdom scribes, who developed land registers and censuses to keep track of individuals’ tax obligations. “It was a new technological as well as social environment,” says Muhs. “There were thousands of scribes who could use documentation as a powerful tool to make sure everyone paid their taxes.”

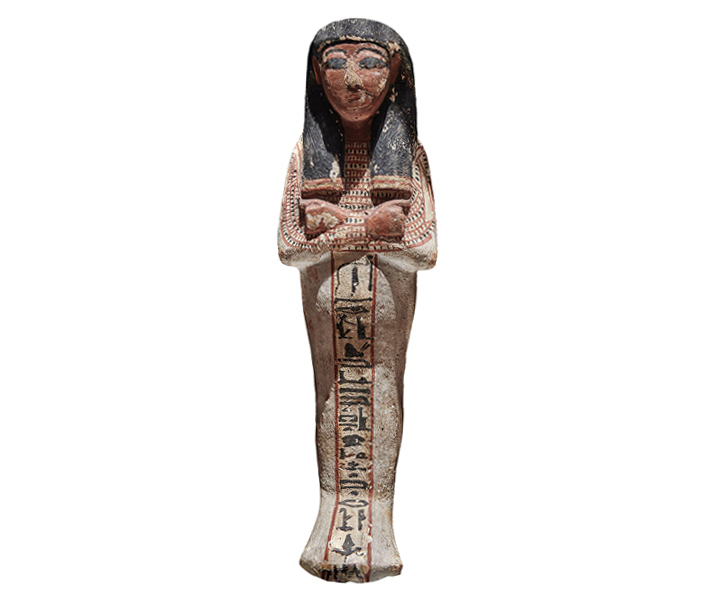

Ancient Egyptians assumed that they would have to pay taxes in the afterlife, too—and that the system could be gamed. “In life, privileged Egyptians could send a substitute to perform their labor taxes for them,” says Muhs, “so they came to believe that something similar could be done in the afterlife.” During the Middle Kingdom, Egyptians began including small figurines, known as ushabti, in their graves. Ushabti were inscribed with spells ensuring the figurines would perform their deceased owner’s labor taxes when called upon. For the next 2,000 years, ushabti helped Egyptians—high status and commoner alike—dodge their taxes for eternity.