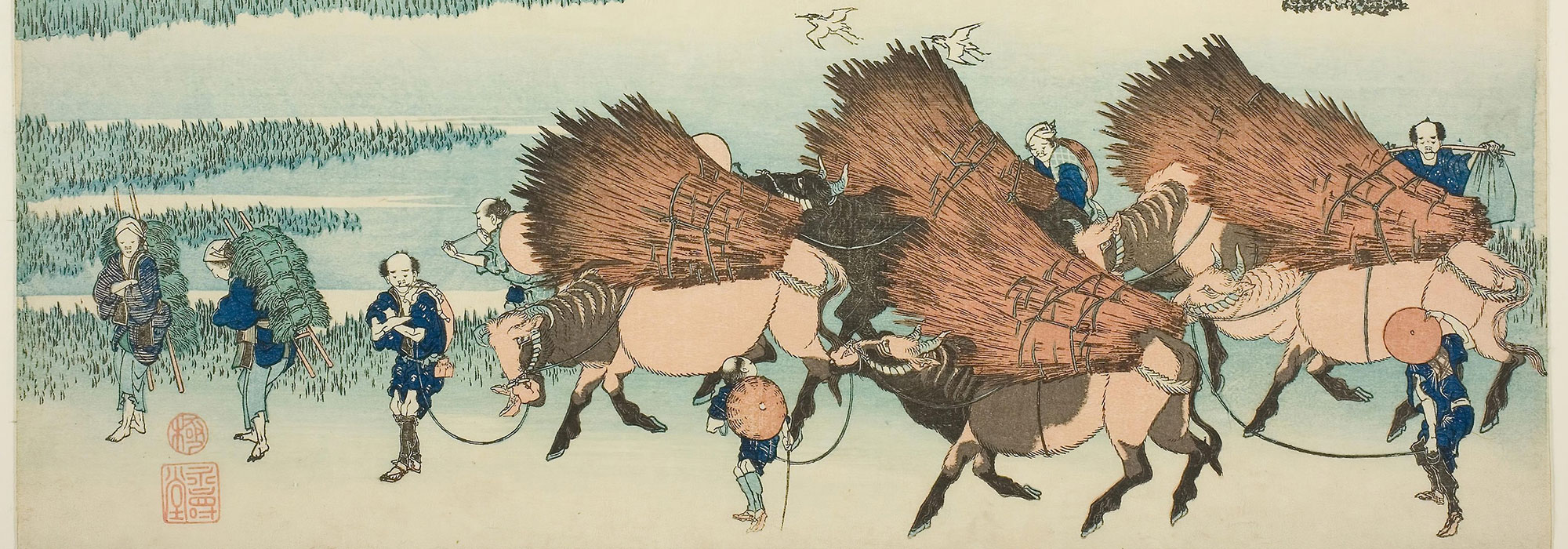

During the Tokugawa era (A.D. 1603–1868), much of Japan was ruled by the country’s military governor, called the shogun, or his retainers. The rest was divided up into several hundred semiautonomous domains overseen by powerful samurai known as daimyo. In these domains, the daimyo were free to set tax rates on local peasants as they saw fit. This included the most important tax, nengu, which claimed a portion of each domain’s rice yield. According to records from 1868, nengu rates varied wildly across these domains, from 15 percent to as much as 70 percent. Curious to see whether peasants had any impact on the rates they were subjected to, a team of researchers including Abbey Steele, a University of Amsterdam political scientist, analyzed the relationship between nengu rates and peasant tax rebellions recorded throughout the Tokugawa era. These revolts included hanran, large rebellions typically including thousands of peasants, and chosen, mass desertions in which peasants abandoned their fields and threatened not to return until their demands were met.

Steele and her colleagues found that, after controlling for various factors, the domains that experienced the most intense types of peasant tax resistance had, on average, nengu rates 5 percent lower than domains that did not. “Our work shows that peasants appear to have been able to influence the political development where they lived,” says Steele. While the team found that insurrections and desertions were associated with lower nengu rates, they can’t be certain that peasant resistance by itself caused the tax rate to drop. It is also unclear how recorded nengu rates were implemented in practice. Nevertheless, the researchers’ findings illustrate that even people who may seem to be at the mercy of all-powerful rulers will go to great lengths in search of a tax break.