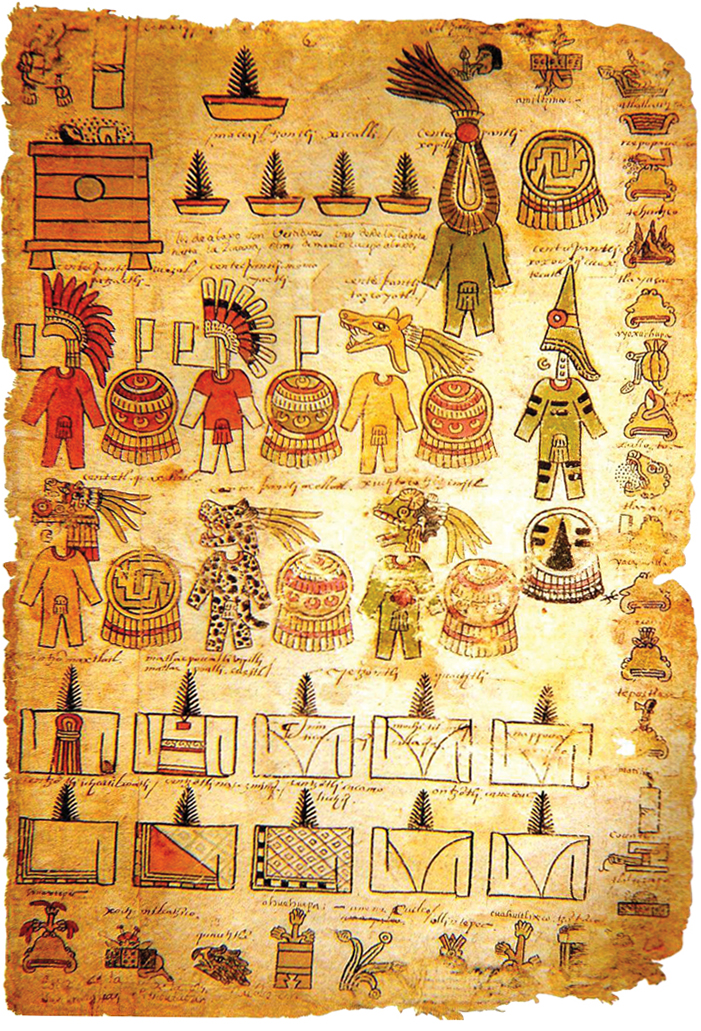

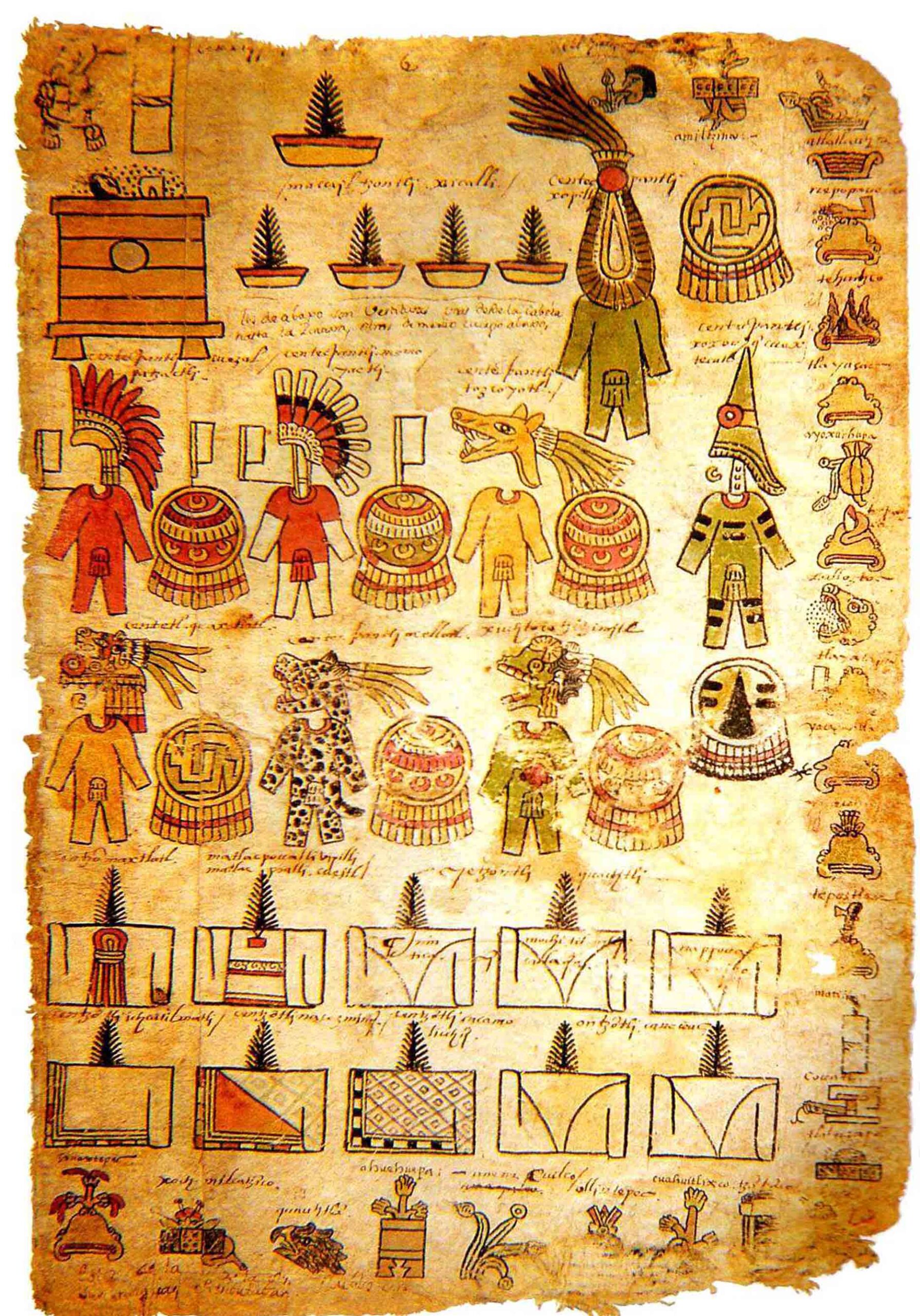

Before the Spanish arrived in 1519, the highest officials of the Aztec Empire could count on the provinces they ruled for an annual yield of 40 jaguar skins, 70 gold bars, 2,200 pots of bee honey, 4,000 loaves of salt, 16,000 rubber balls, and two live eagles, among many, many other items. One province alone was responsible for supplying 128,000 textiles. This expansive inventory is enumerated in a lavishly illustrated codex known as the Matrícula de Tributos, a pictographic narrative that details which goods each province owed to the empire. Scholars have traditionally regarded these as a kind of tribute paid by conquered states rather than as taxes, but Arizona State University archaeologist Michael E. Smith disagrees. “Tribute is booty,” he says. “That’s what a pirate takes. What the Aztecs were doing was definitely taxation.” Smith has identified a bewilderingly complex system of at least 11 different types of taxes levied at the Aztec imperial and city-state level.

Taxes paid at the city-state level were probably much more significant to the average Aztec citizen than those recorded in the colorful record seen in the codex. “The empire worked almost like a mafia protection racket between the various city-states,” says Smith, “and the average person would have seen almost no return on imperial taxes.” On the other hand, local land and market taxes, which were often paid in cacao beans or cotton, funded canals and dams, on which all Aztecs relied. The local system was so efficient and entrenched that in 1532, a Spanish official wrote of the Aztecs that “the activity of paying taxes is so well understood, that I expect they will be paying taxes in gold and silver in no time.”