Not too long ago, archaeologist Rengert Elburg found something that convinced him that “Stone Age sophistication” is not a contradiction in terms. It was a wood-lined well, discovered during construction work in Altscherbitz, near the eastern German city of Leipzig. Buried more than 20 feet underground, preserved for millennia by cold, wet, oxygen–free conditions, the timber box at the bottom of the well was 7,000 years old—the world’s oldest known intact wooden architecture.

Elburg’s team at the Saxony State Archaeological Office removed the ancient well in a single 70-ton block, and brought it back to their lab in Dresden for careful excavation, documentation, and preservation. There, they recovered 151 timbers from the well, which, during the Neolithic period, was part of a large settlement that included nearly 100 timber longhouses. Even after so many millennia, the well’s extraordinary state of preservation began to give the researchers clues to the tools and techniques the ancient woodworkers used. They learned, for example, that to reinforce the bottom of the well, prehistoric carpenters had fashioned boards and beams from old-growth oaks three feet thick, then fit them together using tusked mortise-and-tenon joints, a technique not seen again until the Roman Empire, five millennia later.

When Elburg examined the wood, he could see not only tree rings but also tool marks. But with nothing to compare these ancient tool marks to, this evidence was hard to understand. Thus, he and a motley collection of archaeologists, amateur woodworkers, historical reenactors, and flintknapping hobbyists have been gathering each spring since 2011 for a most unusual workshop. Held in a forest just outside the town of Ergersheim in the southern German region of Franconia, it’s experimental archaeology with a serious purpose.

Soon, the rhythmic pounding of stone against oak picks up again. The workshop’s goal is to reconstruct a few layers of the ancient well from scratch, beginning with chopping down an oak and ending with finishing the joints. Comparing ancient evidence with the byproducts of the participants’ tree clearing and woodworking, such as the chips that litter the ground after a few hours of chopping and chiseling, will help refine what researchers know about Stone Age carpentry. Every once in a while, the noise stops to allow a researcher with a portable 3-D scanner, which looks a bit like a hand mixer with no beaters, to take progress-report scans of the gouges in the trunks. “It’s the first time we’re using the 3-D scanner in the field,” Elburg says. “We can take the records of tool marks from here and compare them to what we have from the well at Altscherbitz.”

Experiments such as the Ergersheim workshop have a long history. Over the years, such research, combined with ethnographic studies of people still using stone tools in the modern era, have helped shape how archaeologists understand the cultures that used them in the past. This type of research has been especially illuminating for the European Neolithic.

The Neolithic period, also known as the Late Stone Age, began 10,000 years ago in what is today Turkey. It was a time of technological and social change, marking a momentous shift from a mobile, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled farming communities. In Europe, this era began about 7,500 years ago, right around the time the Altscherbitz well was dug. Bringing the Neolithic culture to Europe, Elburg explains, was possible in large part because of advanced technology. “Ground-stone tools enabled these first farmers to clear the woods and build the first permanent houses in Central Europe,” he says.

Around the time farming started in Germany and Denmark, pollen records show there was a dramatic shift in the European landscape. Tree cover declined, and pollen from grasses and shrubs increased. Archaeologists trying to explain this assumed that shifting climate had reduced the forest cover, making it possible for Neolithic farms to flourish. Given the primitive tools available in the Stone Age, their reasoning went, it was unrealistic to think people could have made much of a dent in the primeval forests.

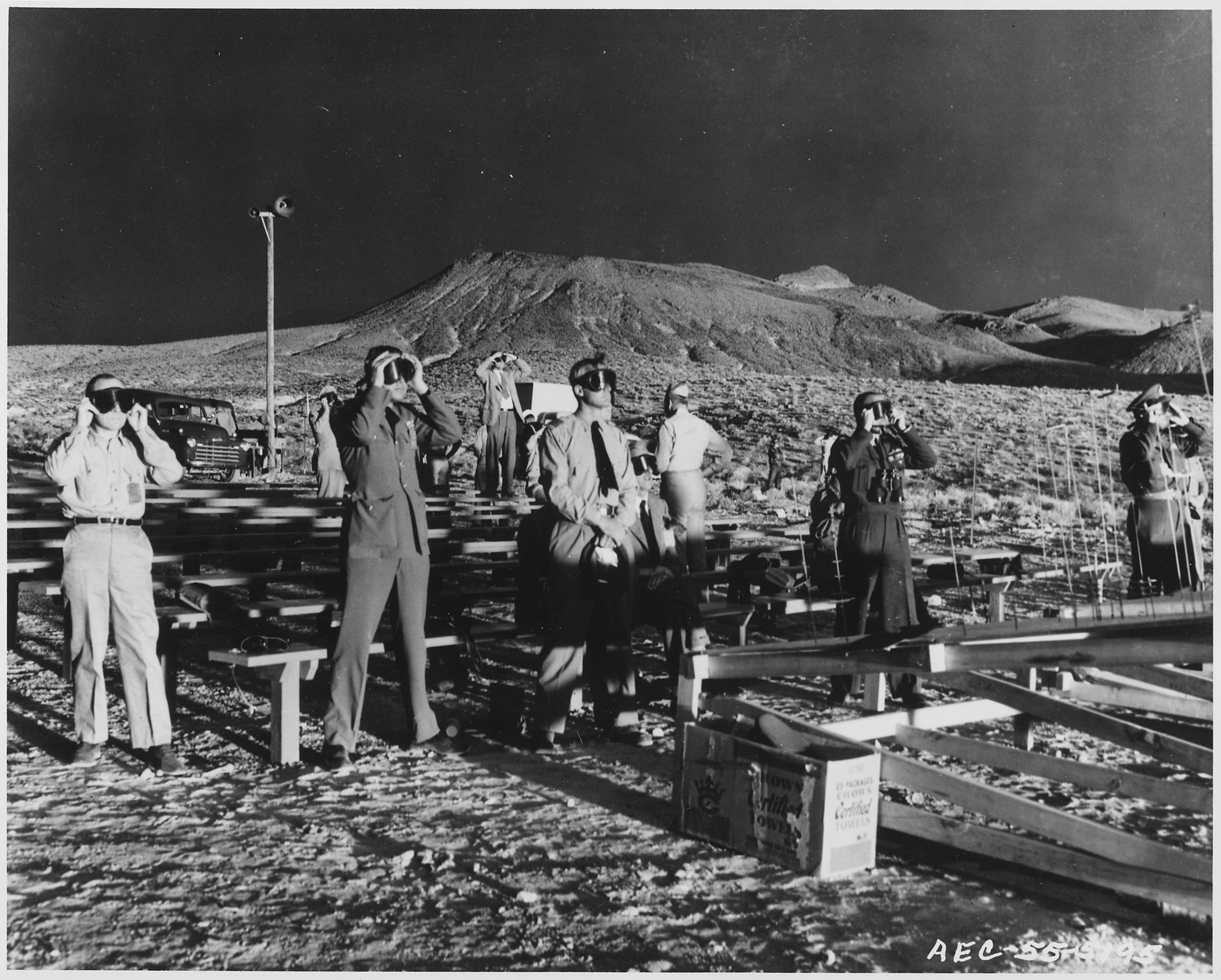

A pollen expert at the Geological Survey of Denmark named Johannes Iversen, however, had his doubts. In 1952, using actual Stone Age flint tools taken from a local museum, he and a few colleagues conducted an experiment in a patch of Danish forest. Photos from the time show them in shirtsleeves, smoking pipes as they swung stone axes. Their first attempts to fell trees were a self-described “fiasco,” according to their journals. “In the course of a few minutes all four of the axes we had brought with us were useless,” the researchers wrote.

As the day wears on, a pattern of labor begins to emerge. In one area, a trio of toppled trees is being split using wooden wedges and mallets. Nearby, long sections of timber are stripped of bark and fashioned into beams and boards. The final stop is a cluster of craftsmen wielding wooden mallets and sharpened bone chisels to make the joints. Overseeing the last station is Anja Probst, a graduate student at the University of Freiburg who specializes in prehistoric bone tools. It turns out that “Stone Age” is something of a misnomer.

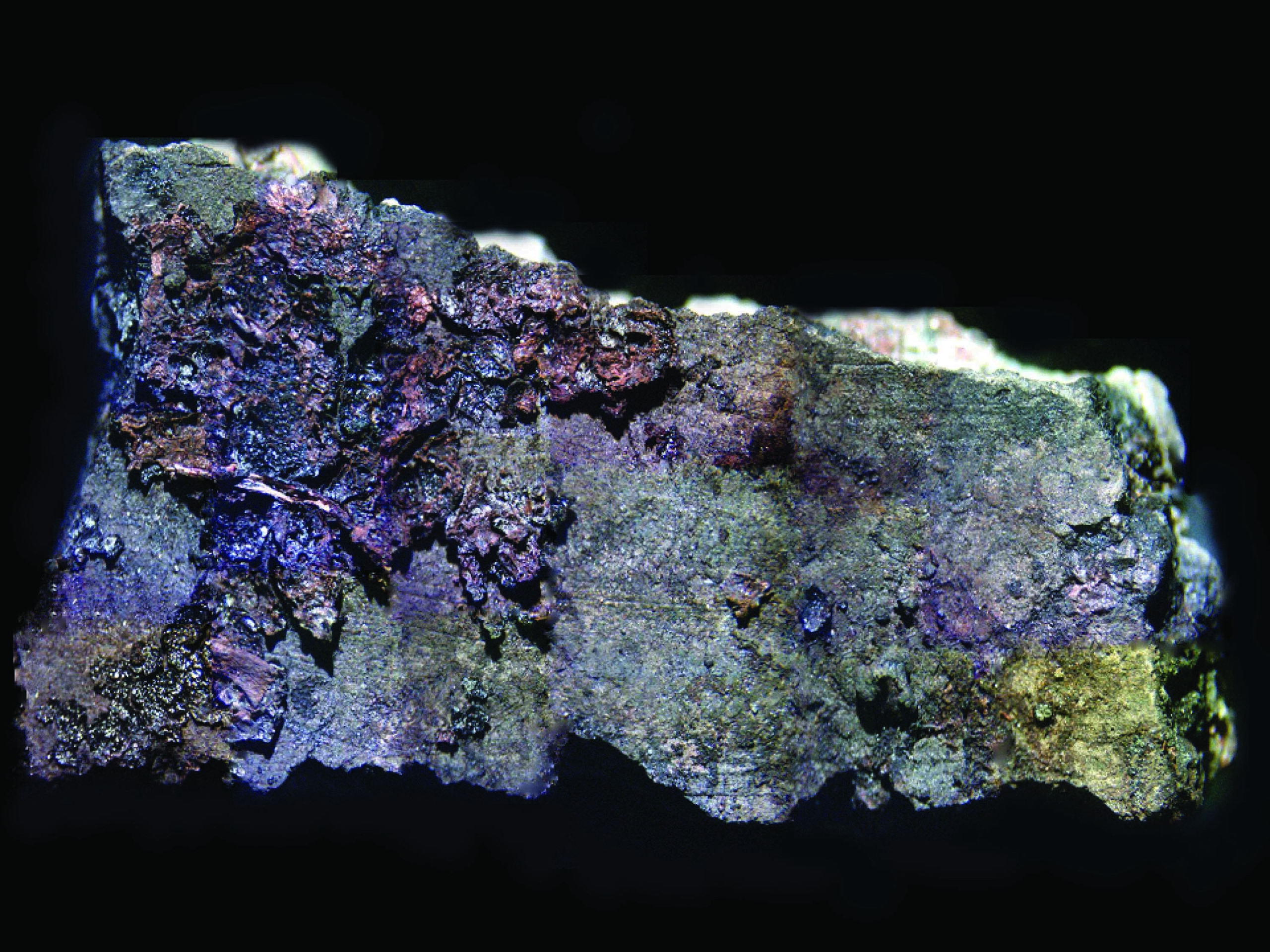

It might be more accurate to call the millennia before the development of metallurgy the “Bone Age,” says Probst. “Bone and antler were actually the most common tools in the Stone Age. You’re already hunting or eating meat, so there are always bones around. Stone was more difficult to get, and had to be transported over many miles.” Close examination of preserved wood from the Altscherbitz well and other prehistoric finds from the area show that chisels were used to make holes and grooves even in hardwood such as oak, and could create perfect square holes in the boards. This sort of fine finishing work needed a lighter touch than the heavy basalt adzes and wedges could provide, and chisels could only be made out of bone and antler.

To prove it, Probst gets cow bones from rare-breed cattle that spend the year outdoors, and resemble the types of animals ancient woodworkers would have encountered. Probst explains that the bones are harder and more durable than those from factory-farmed animals. She then cures, splits, and sharpens them into chisels, which she brings with her to Ergersheim to try out. When they get dull, she rubs the chisels on a bit of sandstone to bring back a sharp edge. Back in the lab, Probst will examine the tools to see what ancient craftsmen were likely using to build wells, longhouses, and other structures. “We look at the wear with a stereomicroscope, an electron microscope, and a white-light interferometer,” she says. “It’s a 3-D surface, and we measure every wear pattern we can see.”

By evening, a frame of wood is taking shape. It will be transported back to Dresden and studied in-depth, but for now Elburg kneels next to the familiar form, comparing the work in progress to a schematic taken from the scans of the Altscherbitz well and nodding in satisfaction. “You have to handle things. By using stone tools ourselves, we can see what works and what doesn’t work,” he says. “Because from your writing desk you can’t say anything.”

Video: Recreating The Neolithic Toolkit

Every spring since 2011, a group of archaeologists and craftsmen have gathered in a forest in southern Germany to bring back to life the tools and techniques of Stone Age carpenters. This video shows the team using the tools they made to fell trees and build a copy of a 7,000-year-old well.