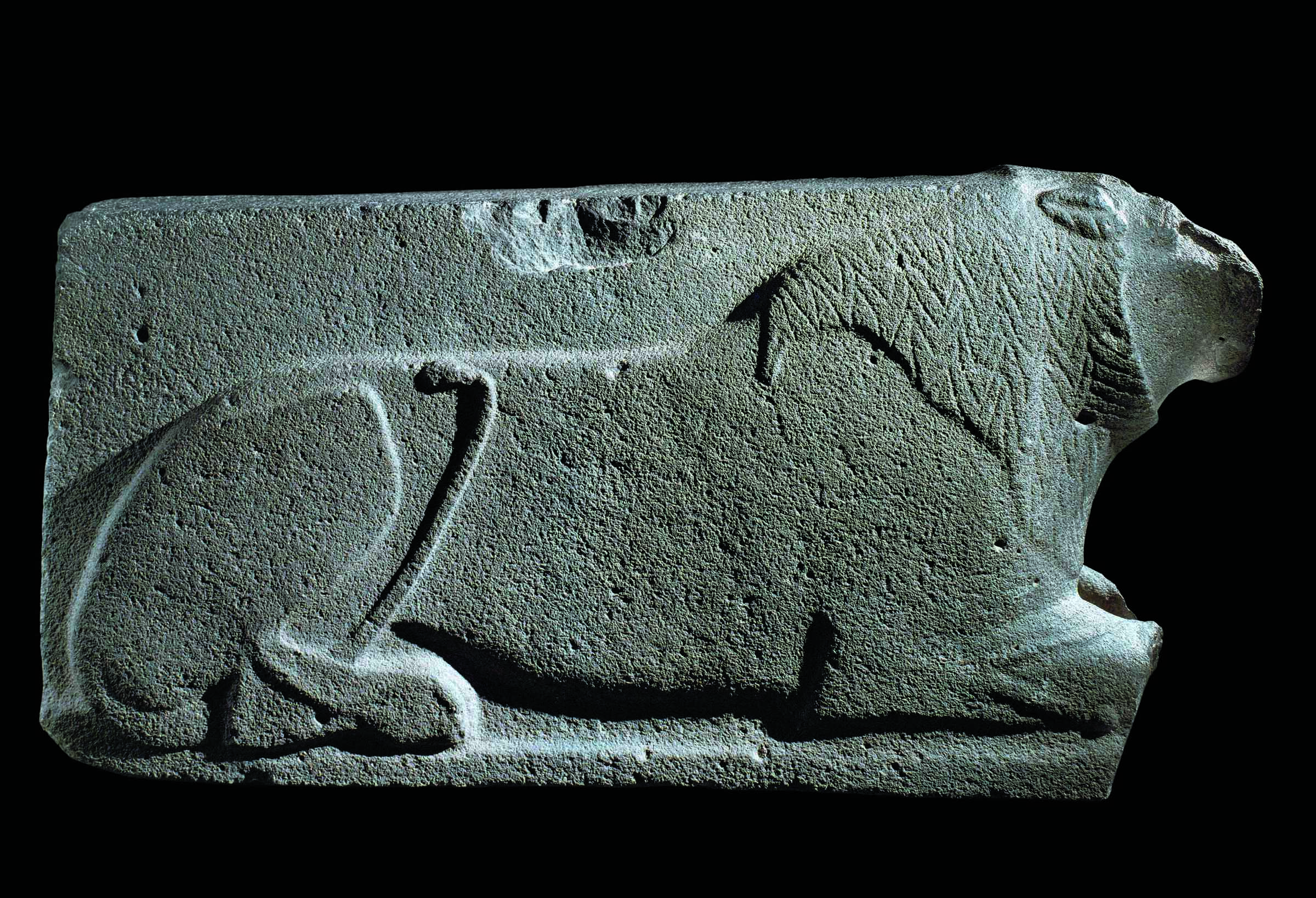

Although people had been living on the Acropolis since the Neolithic period (ca. 4000–3200 B.C.), it was not until the Bronze Age (ca. 3200–1100 B.C.) that the rock became a fortified citadel with a palace. The first defensive wall atop the Acropolis was built in the thirteenth century B.C. by the Mycenaeans, a civilization that thrived in Greece between about 1600 and 1100 B.C. Long after the Mycenaeans were gone, their wall survived—and some sections still do—until it was severely damaged by the Persians in 480 B.C., after which a new 2,500-foot circuit wall was built as part of the fifth-century B.C. building program. In some places, pieces of monuments destroyed earlier in the century were used.

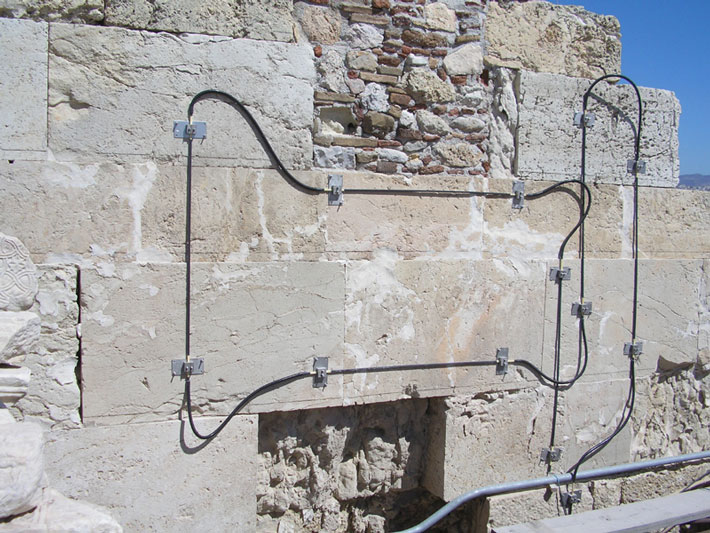

For more than three decades the circuit walls have been exhaustively documented, constantly maintained, and actively monitored using traditional methods, such as inspecting cracks and removing roots and plants, in combination with the latest and most accurate technology available. A complete photogrammetric survey and 3-D scan of the walls has been completed, optical fibers have been installed to measure strain, and a highly precise nickel-iron alloy underground wire has been placed between the Parthenon and the south wall to measure micromovements.

As part of the conservation of the walls, the limestone and schist of the Acropolis itself was also consolidated. Between 1979 and 1993, unstable rocks were anchored to the main mass of the Acropolis in 22 places with stainless steel rods, and gaps and fissures in the rock were sealed with injections of cement.