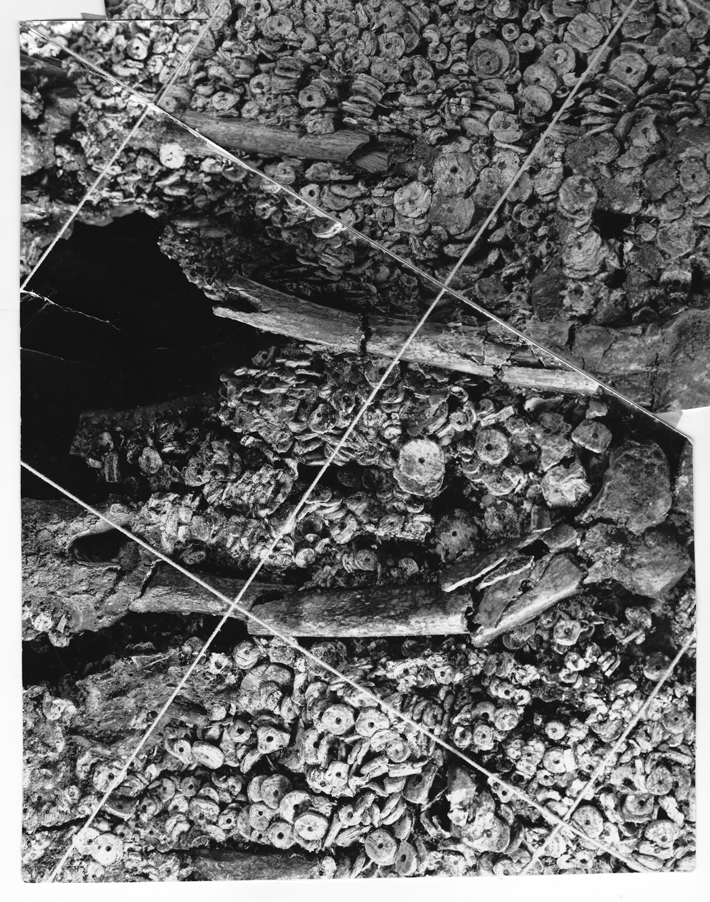

In 1967, archaeologists discovered a spectacular burial of two men accompanied by six male servants inside a mound in the city of Cahokia, which flourished near present-day St. Louis from around A.D. 1000 to 1250. The two bodies were found atop 22,000 shell beads that formed the shape of a bird, which in some Native American cultures is associated with military prowess. At the time it was thought that the burial was a kind of monument to male power, and it was assumed the men were warrior chiefs—part of a male-dominated hierarchy that controlled Cahokia.

When bioarchaeologists led by the Illinois State Archaeological Survey’s Thomas Emerson reexamined the remains, they were astonished to find that the skeletons in the bead burial actually belonged to a man and a woman, and that 12 bodies, including those of multiple women and a child, accompanied them. “We were flabbergasted,” says Emerson. “It’s long been gospel that these were all men.” He thinks the women were high-status members of the city’s nobility and that the discovery shows that class was more important than sex at Cahokia.