Starting from a base in Mesopotamia, the Neo-Assyrian Empire (883–609 B.C.) expanded to control territory that stretched from western Iran to the Mediterranean and from Anatolia to Egypt. In the course of establishing the largest empire in the history of the world up to that point, the Assyrians needed to find ways to bring a diverse range of peoples into their orbit. At times, this involved such heavy-handed tactics as forcibly moving large groups to the Assyrian heartland, where they would be indoctrinated into the Assyrian worldview. But the Assyrians also employed more subtle approaches, as illustrated by a recently discovered underground complex in the village of Başbük in southeastern Turkey.

The site came to the attention of authorities after it was targeted by looters, who had cut into it through the floor of a modern two-story house. “The looters must have hoped to find treasure,” says archaeologist Mehmet Önal of Harran University, who led a rescue excavation of the complex in 2018. “They were caught showing photos of carvings from the complex and looking for customers to buy them.” Önal and his team found that the complex, which was carved out of limestone bedrock, consists of an entrance chamber and an upper and lower gallery. In the upper gallery, they cleared away sediment to reveal a 13-foot-wide relief panel carved into the rock wall that appeared to depict a procession of eight gods and goddesses.

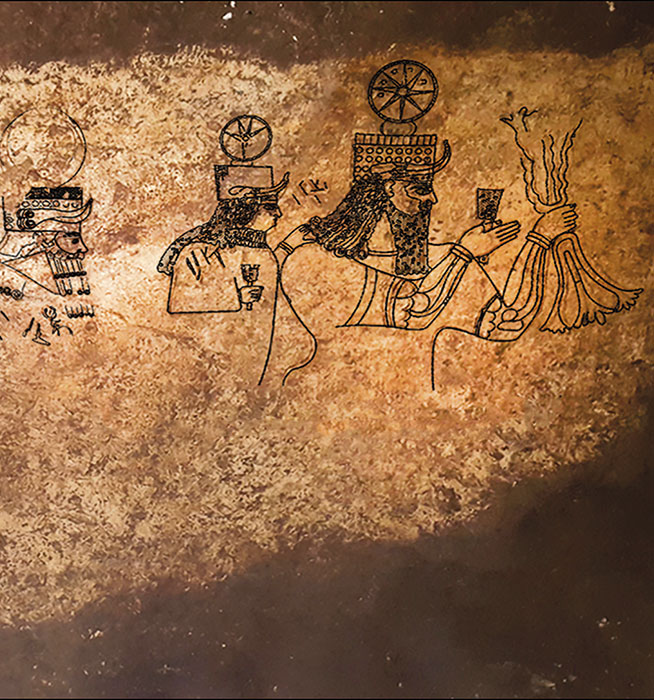

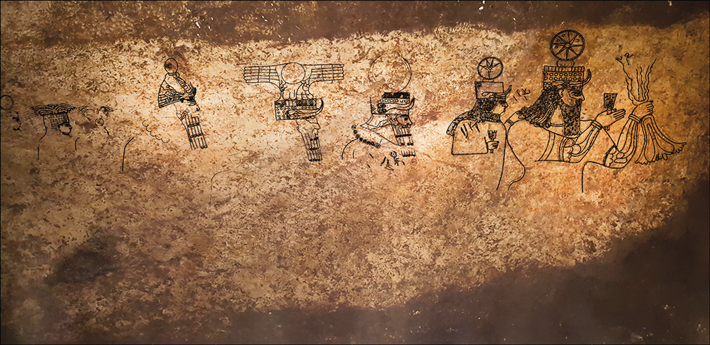

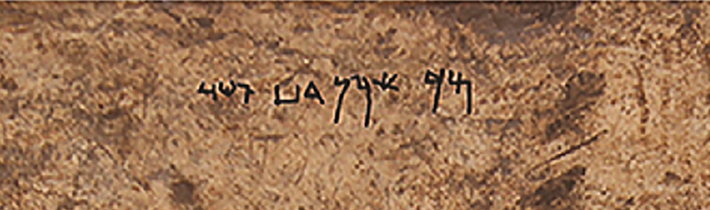

The excavation was cut short due to the site’s instability, but Önal was intrigued by the panel and sent photographs of it to Selim Ferruh Adalı, an ancient historian at the Social Sciences University of Ankara. Adalı was struck by the panel’s unusual blend of Assyrian and local Aramaean features. He was able to identify the first four deities in the procession—three of them based on their attire and accoutrements as well as short inscriptions in Aramaic, the language of the local people in Neo-Assyrian times. First and largest is the storm god Hadad, the dominant deity of northern Syria and southeastern Anatolia in the first millennium B.C., carrying his lightning bundle and wearing a large encircled star on his head. Following Hadad is his consort, Attar’atte, a mother-goddess of fertility and protection, who is depicted wearing a double-horned, cylindrical crown on which a star is set. Next is the moon god Sin, who sports headgear crowned with a crescent and full moon. The fourth deity is recognizable as the sun god Shamash based on the winged sun-disk crown he wears, but the remaining four deities cannot be clearly identified. A longer Aramaic inscription on the panel is largely illegible, but appears to include the name Mukın-abūa of Tušhan, the Assyrian official in charge of the region during the reign of the Neo-Assyrian king Adad-nirari III (r. 810–783 B.C.). While the panel features gods worshipped locally, they are depicted with traits typically found in Assyrian art such as the style of beards and of the muscles in Hadad’s arms.

According to Adalı, this is the first known Neo-Assyrian relief that includes Aramaic inscriptions and features Aramaean deities. It appears to reflect an early phase of the Assyrians’ presence in the area when the new arrivals accorded local belief systems respect in an attempt to win the favor of the populace. “The panel signals how the Neo-Assyrian Empire not only used military might but also tried to negotiate control by participating in various local rituals and adding their own tools to them,” says Adalı. By having his name included alongside portrayals of local deities, Mukın-abūa was likely trying to bolster his influence in the area. The outlines of the deities were incised to a depth of just a millimeter, and the most complete figure, of Hadad, includes only the upper portion of his body, suggesting that the panel was unfinished. “It’s possible that there was local unrest at the time,” says Adalı. “We do know that Mukın-abūa went to another part of the empire on behalf of the Assyrian king to suppress a rebellion. Perhaps something happened to him and he didn’t come back and this relief was left as it is.”