Crocodiles loomed large in the world of the ancient Egyptians. The Nile teemed with the lurking reptiles, and farmers, who made up most of the population, encountered them on a daily basis. While Egyptians were rightly wary of the ferocious predators, they saw a healthy crocodile population as an auspicious sign that the annual flooding of the Nile would be successful, producing fertile soil from which they could raise bounteous crops. They considered crocodiles avatars of the god Sobek, who was known as Lord of the Nile. In cult centers across Egypt, specially selected crocodiles were treated as incarnations of the god. At the aptly named Crocodilopolis in the Fayum Oasis southwest of Cairo, writes the first-century b.c. Greek geographer Strabo, priests fed one such crocodile, named Suchus, a rich diet of bread, meat, and wine, and adorned the beast with precious jewels. To curry favor with Sobek, Egyptians gave mummified crocodiles as votive offerings. “The idea was that the mummy could transmit a message from the earthly world to the god and open up an avenue of communication,” says Lidija Mcknight, an archaeologist at the University of Manchester. “Just as we might light a candle in a church or say a prayer in memory of someone, a similar kind of belief system drove animal mummification in Egypt.”

Archaeologists have discovered thousands of mummified crocodiles throughout Egypt, evidence of how widespread this practice was. But just how such a large number of crocs were sourced has been an open question. At temple sites such as Medinet Madi in the Fayum Oasis, enclosures with large water basins are believed to have served as habitats for raising crocodiles—until their time was up. Ancient writers report that crocodiles were also harvested in the wild. One technique, according to the fifth-century b.c. Greek historian Herodotus, involved placing hooks baited with pork in the Nile. Four centuries later, the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus writes that crocodiles were hunted with spears and nets. Until recently, however, when a team led by Mcknight made an unexpected discovery, archaeological evidence of crocodile hunting was all but nonexistent.

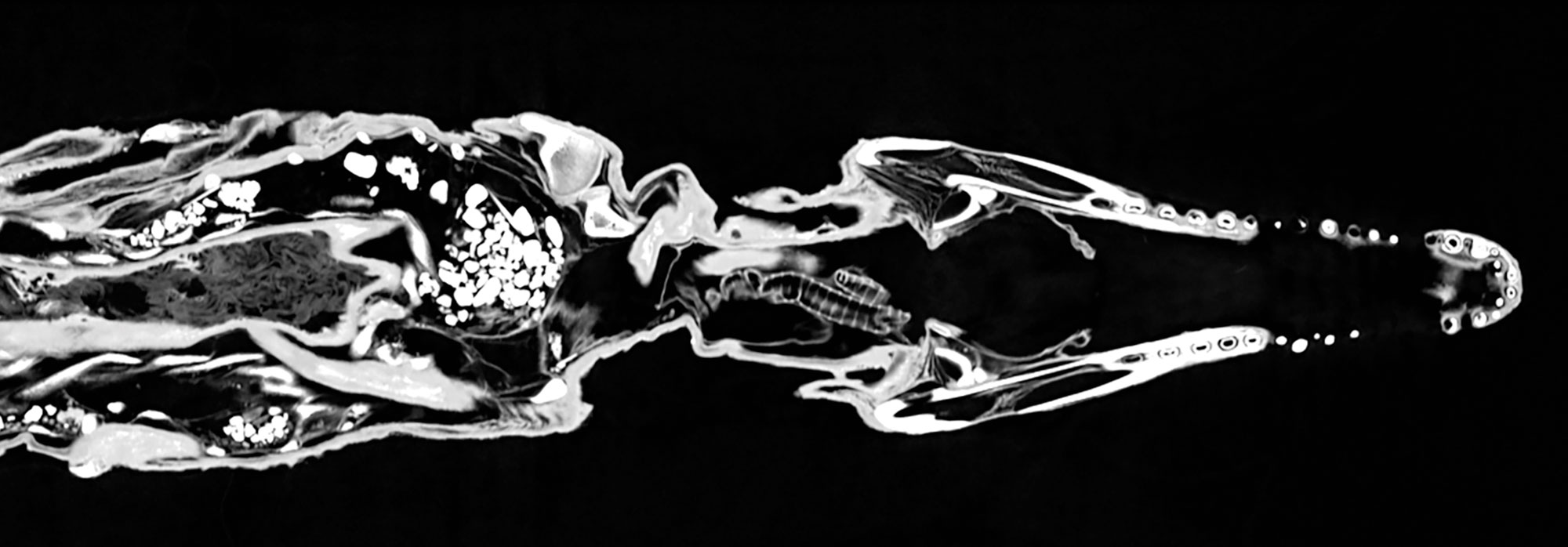

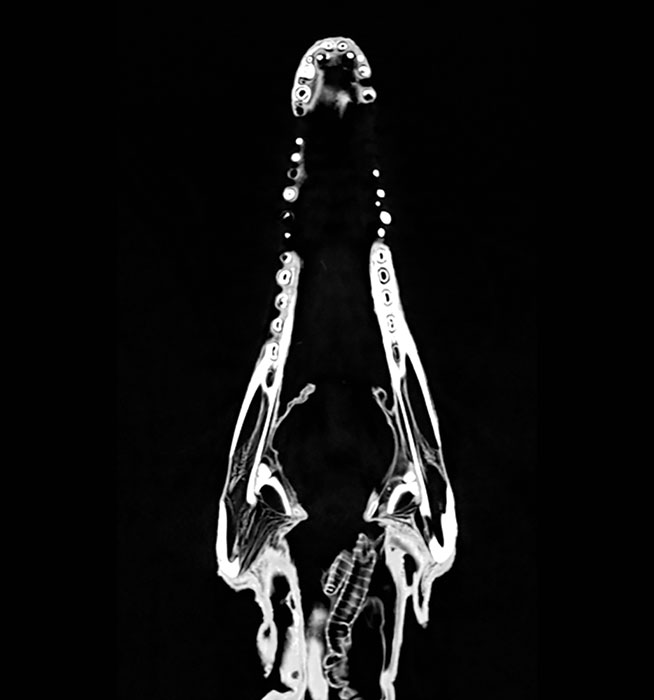

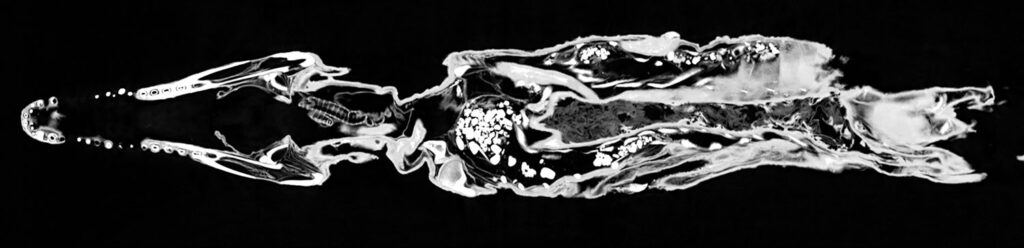

To learn more about crocodile mummification, Mcknight’s team used X-rays and CT scans to peer inside a 7.3-foot-long specimen held at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. In the crocodile’s stomach, they found the intact skeleton of a nine-inch-long fish next to a 1.3-inch-long metal hook. The integrity of the fish’s skeleton suggests it was swallowed whole and that the crocodile died shortly after gulping it down. By all appearances, then, the crocodile was snared with a hook—baited with a fish, not pork as Herodotus had it. The beast was then promptly dispatched for mummification and pressed into service as a votive offering to Sobek. “We have always thought that crocodiles were caught in the wild,” says Mcknight, “but this is one of the only examples we have to show how that might have actually happened.” Researchers believe the reptile met its demise in the first millennium b.c., when animal mummification in Egypt was at its height. (See “Messengers to the Gods”)

The team also found evidence of how animal and human mummification differed. Imaging of the crocodile’s stomach revealed a sizable number of gastroliths, stones consumed to help break down food and regulate the animal’s buoyancy. The presence of these gastroliths indicates that the crocodile’s internal organs were not removed, as was the usual practice when mummifying people. Mcknight points out that natron, a salt used to draw out moisture and preserve the body in human mummification, was not applied to this crocodile, nor to mummified animals in general. Instead, a resinous substance was slathered on its body, which was then wrapped in linen, evidenced by small remaining fragments and imprints of the fabric visible in the resin. “The Egyptians didn’t have the time to spend upwards of forty days preparing an animal mummy like they would with a human body,” says Mcknight. “They seem to have been doing things much more quickly when mummifying animals, probably because there was a massive demand for them.”