In May 1562, Diego de Landa, the highest-ranking Catholic authority in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, received word that a large number of idols, along with human bones and deer meat, had been discovered in a cave near the town of Maní. Landa had spent the previous 13 years as a Franciscan missionary fervently converting the region’s Indigenous Maya people to Christianity and attempting to stamp out pagan worship. Yet here was clear evidence that idolatrous practices persisted—possibly including human sacrifice. Landa commissioned the friars in Maní to investigate this outbreak of heretical behavior among Maya who had already been baptized. People living near the cave confessed that they had appealed to the idols in an attempt to increase rainfall and to obtain assistance in hunting deer. Landa’s fellow Franciscans and a network of Maya informants fanned out across the peninsula, confiscating a massive collection of idols. By July, according to Spanish legal records, they had investigated 6,300 Maya, subjecting many to harsh questioning under torture. They had also meted out punishments including ritual humiliation, public flogging, and forced servitude to more than 4,500 people. At least 157 individuals had died as a result, 32 had been permanently maimed, and dozens had been driven to suicide.

This reign of terror reached its height on Sunday, July 12, 1562. On that day in Maní, Landa presided over an auto-da-fé, meaning “act of faith,” a ritualized display of public penance used during the Spanish Inquisition. At the head of a long procession walked Landa and the province’s governor, Don Diego Quijada, guarded by armed Spaniards. After them came friars who served as ecclesiastical judges in the trials of Maya accused of heresy. Next marched Maya assistants to the friars carrying 64 scarecrow-like effigies representing deceased Maya leaders deemed guilty of idolatry and 114 sets of bones belonging to these leaders that had been dug up for the occasion. After the procession, these deceased leaders would be sentenced to a sort of spiritual death, and their effigies and bones would be set on fire.

Next came 69 living Maya leaders, wearing sanbenitos. These yellow garments, which were decorated with the St. Andrew’s cross, the wearer’s name, and a description of their alleged crimes, were markers of shame associated with the Inquisition. Nine of these leaders, considered the most culpable, also wore pointed caps called corozas. When the procession finished, all 69 Maya leaders would be sentenced to severe punishment, which could include having their hair shorn, wearing the sanbenito for several years, receiving hundreds of lashes, and performing years of forced labor in the cathedral of the provincial capital, Mérida. Once their penance was completed, the offenders would be allowed to rejoin the Church. At the rear of the procession were at least 95 prominent Maya whose offenses were considered comparatively minor. They were naked from the waist up, had ropes around their necks, and carried green candles of repentance. After being lashed, their penance, too, would be complete.

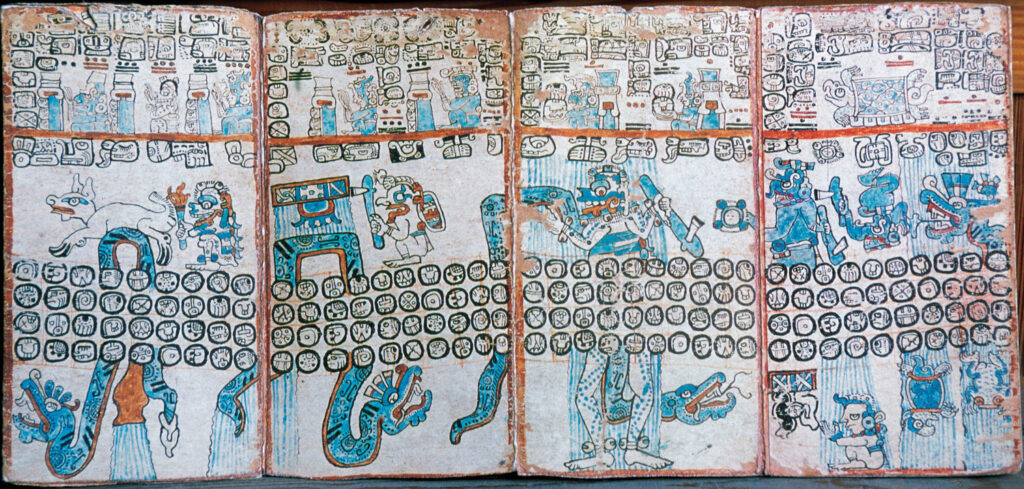

Many of the Maya charged during the auto-da-fé were required to carry idols that they had been caught hiding or worshipping. After being sentenced, these penitents were led to a bonfire where they were forced to destroy the objects as a demonstration of their Christian faith. “These were often heirloom pieces that had been used by Maya families as religious objects passed down from their ancestors and protected for generations,” says historian John Chuchiak of Missouri State University. “They had to physically smash them on the ground, step on them, spit on them, and throw them in the fire.” According to Spanish government records, many thousands of idols and other cultural artifacts were demolished during the auto-da-fé in Maní. Also burned were 27 codices, folded books featuring hieroglyphs written on bark paper that recorded details of Maya ritual practice. More than 100 such codices were destroyed during the Spanish colonial period (1542–1821), leaving—at most—four known to exist today. “The auto-da-fé of Maní represents a destruction of cultural patrimony at a massive scale,” says Chuchiak.

Evidence of this auto-da-fé lay hidden for more than 450 years after Landa orchestrated the savage event in Maní. Archaeological work in the small city was largely focused on its cenote, a sinkhole that provided water to the ancient population, in which Yucatán’s earliest ceramics, dating to around 1000 b.c., have been unearthed. Then, in January 2015, as part of a campaign to have Maní declared a Pueblo Mágico, or Magical Town, a designation intended to encourage tourism in out-of-the-way Mexican locales, workers began to dig drainage holes in a plaza in front of the palacio municipal, or city hall. They soon came upon a large concentration of ceramic fragments and contacted authorities at Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History. Archaeologist Tomás Gallareta Negrón was called in to carry out a limited rescue excavation in cooperation with Fomento Cultural Banamex and the Yucatán government.

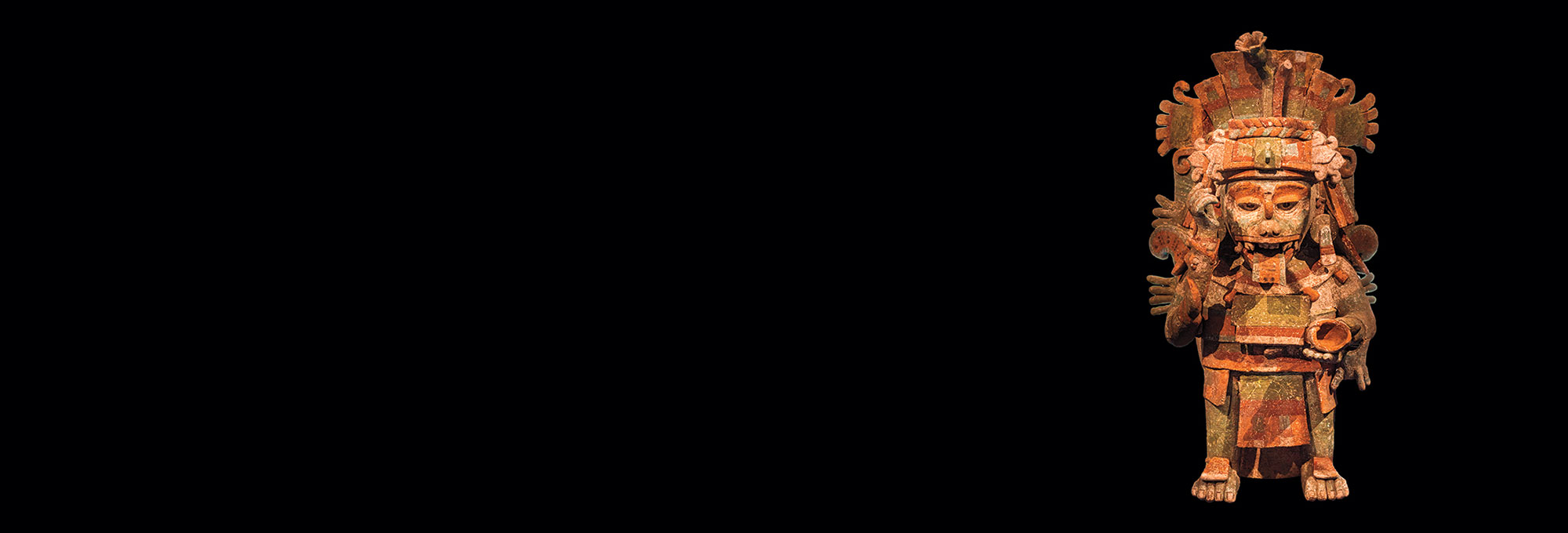

In all, several thousand sherds were uncovered in front of Maní’s city hall. Some of the fragments were found intermingled with pieces of charcoal and show traces of burning. Archaeologists have determined that almost all are parts of a specific type of incensario, or incense burner, dating to the Late Postclassic period (1300–1450). These vessels typically measure between four and 20 inches tall and were used to burn fragrant resins and gums such as copal or rubber as offerings. They generally include a representation of a deity, such as the creator god Itzamná or the rain god Chahk, and their purpose was to link the living Maya to their gods and ancestors.

Archaeologists concluded that these fragments were remnants of the thousands of idols destroyed during Landa’s 1562 auto-da-fé. “It’s exclusively incensario fragments of one type, and that’s what has led us to make the case that what you’re looking at is the moment in time when Diego de Landa stood there in Maní, smashed the idols he had collected, and then burned and buried them,” says archaeologist George Bey of Millsaps College. “This is the first artifactual evidence of that moment in history.” The archaeologists found that the incensarios had been pulverized into extremely small pieces and then mixed together, as if to make it impossible to ever reassemble them. “They were treating these things like they were something created by the devil, so they wanted to destroy them totally,” says Gallareta Negrón. “It was as if they were saying, ‘Look at what we are doing with your gods.’”

According to Chuchiak, the results of even this limited excavation provide a rich complement to the documentary record. “The quantity of pieces along with the burned material is just amazing,” he says. “We have eyewitness testimony of what happened, but when you combine that with the archaeological evidence, it really brings to light a historical event.” One detail of the auto-da-fé missing from the historical record, however, is exactly where it took place. Some claim it was carried out in the atrium of Maní’s church, but the discovery of the incensario fragments in front of the city hall contradicts this assertion. In 1562, that building was the palace of Francisco de Montejo Xiu, the most powerful Maya chief in Maní. Xiu was one of the leaders who was forced to wear a sanbenito and coroza during the auto-da-fé and received particularly severe punishment. Chuchiak says it makes sense that the auto-da-fé, in which justice was served by secular authorities on behalf of the Church, would have been carried out in a public place. “The Spaniards were displaying demonic images, and they wouldn’t do that in the holy atrium of a church,” he says. “Idols were stored in the atrium, but they were all transported to the plaza for destruction.”

Landa was born in 1524 into a well-connected family in the small Spanish town of Cifuentes. By the age of 10, he had become a page in the household of the town’s count. This afforded him the opportunity to befriend prominent members of the Spanish court, including the future king, Philip II (reigned 1556–1598). Landa joined the Franciscan order when he was 16, entering the monastery of San Juan de los Reyes in the city of Toledo. There, he met visiting friars from the New World who shared thrilling tales of converting the natives, combating idolatry, and risking martyrdom. “These missionaries were seen as the shock troops of Christianity,” says Chuchiak. “They called themselves spiritual conquistadors, going out against the forces of the demons.” After continuing his studies at a religious institution called a convento outside Madrid, Landa was granted permission to join the missionary ranks on an expedition to Yucatán in 1549.

At this point, the Spanish controlled only a small portion of the peninsula, having established a colony six years earlier after several failed attempts. They had founded a single city, Mérida, along with several smaller towns, and completed four conventos, including one in Maní. Landa was one of just 19 friars in a territory inhabited by hundreds of thousands of Maya. There were significant tensions between the friars and Spanish settlers, or encomenderos, who were granted the right to draw labor and to exact tribute from groups of Maya villages. The encomenderos were supposed to assist in converting the Maya, but were typically more interested in exploiting them economically, often turning a blind eye to their traditional ways of worship.

Shortly after his arrival in Yucatán, Landa was sent east from Mérida to establish a new mission in an area untouched by Christianity. At first working with a more experienced friar, and then on his own, Landa established a major monastic complex in the Maya city of Itzmal, which the Spanish renamed Izamal. Landa was generally acknowledged to be the most energetic and driven of the Franciscans on the peninsula and spent a great deal of time spreading the gospel in Maya villages several days’ walk from Izamal. “He goes by himself into inhospitable territory, risking his life in this very brutal climate, preaching about the evils of the old gods, and trying to convert the natives,” says Chuchiak.

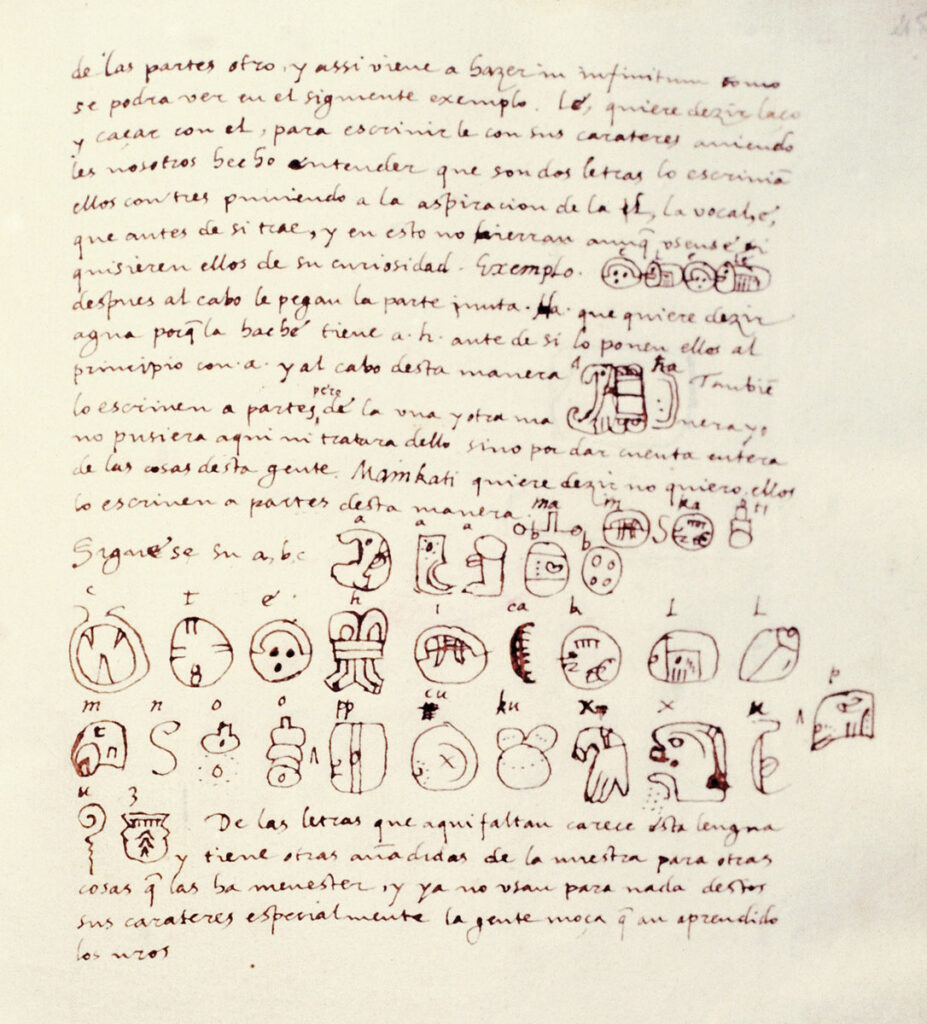

Although Landa would go on to destroy irreplaceable sources of knowledge about the Maya in his auto-da-fé, during his missionary work he recorded a great deal about their culture and religion, some of which was included in a volume known as Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán, or Account of the Things of Yucatán. This text features copious details about the Maya writing system as well as the Maya calendar and religious practices, including idol worship and human sacrifice. “Landa sat down with Maya speakers and asked them to write out glyphs for various alphabetic sounds. He provided a sort of Rosetta Stone for deciphering Maya glyphs,” says Bey. “He also spent a lot of effort trying to convert communities and working with younger elites, teaching them Spanish and bringing them into his religion.” Upon learning that people he thought had converted to Christianity were still worshipping idols and had forbidden codices in their possession, Landa felt an acute sting of betrayal.

When Landa arrived in Yucatán, it was part of the colonial province of Guatemala and thus subordinate to provincial religious authorities. In 1561, however, Yucatán became its own province, and Landa was made head of the Franciscan order there. When he learned of the idolatrous behavior near Maní in May 1562, Landa believed that he had free rein to pursue the heretics. By all accounts, the inquisition he oversaw was extremely zealous, implicating Maya from all walks of life, including many who served in Catholic churches as choirmasters or sacristans. Landa was equally dedicated to gathering codices and idols that could be destroyed during the auto-da-fé. “There are descriptions of mountains of idols piling up,” says Chuchiak.

Some scholars have suggested that Landa was so fixated on assembling an impressive quantity of idols for the auto-da- fé that he ordered his friars to roam far from Maní in search of incensarios. The friars’ Maya assistants are thought to have found rich sources of incensarios at abandoned Maya sites such as Mayapán, not far from Maní, and Cobá, 100 miles east of the town, near Yucatán’s east coast. At the time, these sites were still considered sacred by the Maya, who visited them to make offerings. “The idea was that Landa was asking his assistants to bring to Maní as many incensarios as possible to show how big a problem idolatry was among the Maya,” says Gallareta Negrón. “He wanted to be able to put on an exemplary show, to give them a lesson they would never forget.”

To test the hypothesis that the incensarios came from far and wide, the archaeologists selected 20 fragments unearthed in Maní and analyzed their chemical and mineral compositions. Leslie Cecil, an archaeologist at Stephen F. Austin State University, compared the results of this analysis with samples from various locations in the region. She found that most of the sherds do appear to have come from ceramics originating in Mayapán. In addition, two or three fragments incorporated crushed pieces of pottery from the Late Classic period (a.d. 600–900). The practice of including pieces of earlier pottery in Late Postclassic incensarios was limited to certain areas of the Maya world. Using chemical analysis, Cecil determined that these hybrid fragments likely came from northern Belize, far from Maní on the east coast of the peninsula. “There was some exchange and trade of incensarios, so they may have been in the area already,” says Bey. “But the results provide some indication that Landa was scrounging around for incensarios. It raises the possibility that he was trying to plant evidence to convince the civil authorities that these people were rabid pagan idol worshippers who killed children and were reading prohibited manuscripts.”

Francisco de Toral, the first bishop of Yucatán, arrived in the province in October 1562. Inundated with complaints about Landa’s brutal practices from the Maya and the encomenderos alike, Toral put an immediate end to the anti-idolatry campaign, reported Landa to King Philip II, and overturned the punishments that had been handed down at the auto-da-fé. “Landa realizes he is going to have trouble,” says Chuchiak. “He escapes to Spain literally in the middle of the night before the royal order comes to bring him back.” In Madrid, Landa was brought before the Council of the Indies, the administrative body that oversaw Spain’s colonies in the Americas, to face charges that he had improperly usurped the power and function of an inquisitor. Despite Landa’s claim that this power was rightfully his as the highest religious authority in the province, the council was inclined to decide against him. However, the king, who knew Landa from childhood, intervened and turned the case over to the Franciscan order, which declined to discipline him.

Rather than facing censure for his actions in Yucatán, Landa was seen as an expert on converting the Maya. Philip summoned him to confer on whether an official inquisition tribunal should be given authority over Native people in the Americas. Landa advised against this, instead suggesting that bishops should oversee such inquisitions, the approach that was ultimately adopted. Landa was soon able to take advantage of this policy. When Toral died in 1572, Landa was sent back to Yucatán as the new bishop. With no question of his authority, he resumed his unforgiving approach, punishing more Maya than he had before and launching additional autos-da-fé. This time, Landa had an added layer of protection. Pope Gregory XIII, who had installed him as bishop, issued a special papal bull exonerating Landa for any wrongdoing he might have committed and prescribing excommunication for anyone who alleged he had committed violations while acting as an inquisitor. “Landa destroys two Spanish governors who accuse him of having done illegal things,” says Chuchiak. “He brings out the papal bull and says, ‘Well, you are excommunicated.’ And he got revenge on all the encomenderos who had testified against him.”

With the perspective of almost five centuries, it’s clear that the auto-da-fé in Maní was a key juncture in Spanish colonial history, a moment when the fledgling colony’s religious authorities violently exerted control over their subjects and forced them to accept their creed. “The auto-da-fé of Maní is really, as they say in Spanish, parteaguas, a watershed,” says Chuchiak. “There’s a before and then there’s an after. It is one of the most important events in the religious and cultural history of the Maya under Spanish colonialism. When you start controlling people’s minds and beliefs, you have true control. So, the auto-da-fé of Maní is really Spanish colonialism writ large.” To Bey, the discovery of destroyed incensarios is all the more important given how consequential the event was. “The archaeology provides actual evidence of the auto-da-fé,” he says. “To hold the history in your hands, to dig it out of the ground, really makes the moment come to life.”

Video: Searching for Heretics

On Sunday, July 12, 1562, Diego de Landa, the highest-ranking Catholic authority in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula presided over an auto-da-fé, meaning “act of faith,” in the town of Maní. On that day, more than 150 prominent Maya people were punished for acts of heresy including worshipping idols and possessing books called codices that recorded details of Maya ritual practice. As part of the auto-da-fé, many thousands of idols and other cultural artifacts were demolished, and 27 codices were burned. To see a reenactment of the auto-da-fé, click on the video below. To provide English translation, click on the box labeled CC.

The reenactment was produced by Antonio Rodríguez Alcalá of Anáhuac Mayab University, John Chuchiak of Missouri State University, Zoraida Raimúndez Ares of the Complutense University of Madrid, Maria Felicia Rega of the Institute of Heritage Science of the Italian National Research Council, Luis Díaz de León of the Autonomous University of Yucatán, and Hans B. Erickson of Missouri State University.