In the shade of a ground-floor parking deck inside a campus garage, Santa Clara University archaeologist Lee Panich points out a dark rectangle etched into the gray concrete surface. It marks the foundation of an adobe structure, one of the few physical reminders of a part of California history usually left out of the books. Between 1777 and 1833, what is today the city of Santa Clara was the site of a Spanish missionary outpost. Home to a few Franciscan friars, a handful of Spanish soldiers, and hundreds of Indigenous Californians, it was one of a string of missions that extended the reach of the Spanish Empire nearly 2,000 miles north of Mexico City in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

In 2012, construction work prompted the university to dig up an area the size of a city block a few hundred yards from the campus’ mission-style church, built in 1926 after a fire destroyed the original. Historical records showed that many of the mission’s Native inhabitants were crowded into long adobe barracks near the mission church like the barracks whose foundation is marked in the parking garage. During the excavation, archaeologists found evidence—postholes, artifacts, and plant remains—that other Native residents had made their homes nearby in dwellings constructed of lightweight tule reed, creating a bustling town around the church. Members of Native American tribes from across the San Francisco Bay Area lived alongside each other, for perhaps the first time. “This was the core of the Native neighborhood,” Panich says, walking out into the bright California sun. “The only way you could have found it was with ground-penetrating radar or a big construction project like this.”

The soil stains left by postholes and firepits weren’t all that researchers uncovered. Hundreds of obsidian tools, glass and shell beads, and other finds now rest in dozens of cardboard storage boxes at the university. These artifacts and others are helping to illuminate how Indigenous Californians reacted to Spanish missionaries—and how their cultures outlived the missions, persisting long after Spanish rule ended. At Santa Clara and other sites across California, archaeologists are working to better understand the mission period, which began in 1769 with the establishment of Mission San Diego and ended in 1833 when the missions were dissolved by Mexican authorities.

This 64-year period is typically thought of as the end of the state’s Indigenous communities. “The predominant story is that Native people had their time and that it ended in the mission period,” says Tsim Schneider, an archaeologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a member of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, a group made up of Southern Pomo and Coast Miwok people. For more than a century, that dark narrative has dominated how California’s colonial era is remembered. But new excavations in the Bay Area and new studies of collections in museum and university storerooms are allowing researchers to reconsider that old interpretation.

Over the past decade, Panich and others have uncovered evidence that Indigenous Californians maintained their traditions throughout the mission period, both within and outside the missions’ adobe walls. “People thought Natives came to the missions and lost their culture,” Panich says. “You can look at the archaeology and see that wasn’t the case.” The story archaeologists are telling now is a hopeful one in which Native communities in and around San Francisco responded to the missions by retreating to remote areas or by adapting their traditions to cope with the new European ones. In fact, these Californian Native Americans are still here. “Histories leave out the survivors,” says Schneider. “We’re putting people back in the picture.”

California was once home to hundreds of Native groups with several dozen mutually unintelligible languages. Their first fleeting contact with Europeans was in 1542, when Spanish explorer Juan Cabrillo sailed up the California coast. A few decades later, the English explorer Sir Francis Drake made landfall near San Francisco. Past excavations have uncovered fragments of sixteenth-century Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) pottery from China fashioned into scraping tools and beads. According to Schneider, this is evidence that Coast Miwok people were interacting and exchanging material with Drake’s crew and others who stopped briefly in the region.

It wasn’t until the late 1700s that Spanish colonists began streaming into California in earnest. The 21 missions they founded, stretching from San Diego to Sonoma, 20 miles north of San Francisco, left an indelible imprint. Even today, the geography of California is shaped by the missions. The Camino Real, the “Royal Road” that linked then-remote outposts with Spanish colonies farther south, still forms the main streets of many California towns along the colonial highway. And some of California’s best-known towns and cities, from San Diego and Santa Barbara in the south to Santa Cruz and San Francisco farther north, began as lonely mission churches.

The outposts were a way for the Spanish Empire to lay claim to California with relatively few colonists and little expense. Each mission was situated about a day’s journey from the next and was supervised by one or two priests. Archives kept by the Franciscan friars who ran the missions recording births, baptisms, and deaths show that thousands of Indigenous Californians were rounded up and brought to the missions to be converted to Christianity, sometimes by force. The new converts lived at the missions—often unwillingly, able to leave only with permission from the friars in charge—and labored for the Spanish. They grew European crops such as barley, wheat, apples, and pears, and herded cattle, whose hides and tallow were sources of income for the church. Many lived in adobe barracks like the one whose foundations were uncovered in Santa Clara, a dramatic change from their traditional homes, which would have been round houses made of wood and tule reeds. Others, meanwhile, refused to move to the missions, continuing to live in their traditional villages during this period and beyond.

Mission records paint a grim picture of the toll the system took. Of an estimated 300,000 Native people living in California before the Spanish arrived, only about 20,000 were left in 1834. Church records show that more than 8,200 Native people died from European diseases such as measles or from the maltreatment and malnourishment they were subject to in the space of a few decades at the Bay Area missions: Santa Clara, in the heart of what is now known as Silicon Valley; San Jose, located a few miles from what is now Fremont; the San Francisco outpost at the entrance to the San Francisco Bay; and those to the north in San Rafael and Sonoma.

After a little more than 60 years, the missions came to an end. Mexico, which controlled much of modern-day California at the time, gained independence from Spain in 1821. The missions became Mexican government property and their land was sold off. Over the next century, the surviving Indigenous people were collected on rancherias, the California equivalent of reservations, which were often small pieces of rugged, remote land where it was difficult to make a living.

In the 1920s, a University of California, Berkeley, anthropologist, Alfred Kroeber, sought out elders from various Bay Area tribes as part of a larger effort among anthropologists of the time to document “vanishing” Indigenous cultures. Kroeber and his students compiled place names, vocabularies, and details about religious practices, traditional dances, diet, and more. Because the people they interviewed spoke English and Spanish and did not act the way Kroeber imagined Native people should, he concluded that the Ohlone, Coast Miwok, Yokuts, Mutsun, and other tribes that had once lived around the San Francisco Bay were “extinct as far as all practical purposes are concerned.” That assumption has shaped archaeological research in the century since. Native people and their culture had been wiped out by the missions, the thinking went, so looking for evidence of Indigenous culture after 1769 did not serve any purpose.

Beginning when he was a graduate student, Schneider was determined to change that narrative. The federal government stopped recognizing Schneider’s Coast Miwok tribe in 1958, forcing its members to spend the next four decades fighting to prove it still existed. This effort culminated in the tribe winning back federal recognition in 2000 and served as a reminder of the practical consequences of Kroeber’s claim that California’s Indigenous people had vanished. Schneider became interested in how his ancestors and other Native people managed to survive and maintain their culture despite enforced conversion and the difficult living conditions of the missions. “The idea is to think about colonial sites differently—not as an end point, but as a waypoint,” he says. “People did the mission thing for a few decades, then went on to find other ways to live.”

Between 2007 and 2009, Schneider conducted excavations at a trio of shell mounds at China Camp State Park north of San Francisco. The mounds, made up mostly of centuries’ worth of discarded mussel, oyster, and other shells, are massive—the largest is 15 feet tall and 145 feet across. Such shell mounds are now a rare sight, but archaeological surveys from the early 1900s—before freeways, factories, and office parks transformed the landscape of the Bay Area—documented more than 400 similar examples. More than just trash dumps, they often served as village sites and locations for burials.

Yet until recently, archaeologists considered these once-ubiquitous features of the landscape part of California’s prehistory. Life on and around the Bay Area’s shell mounds, they thought, ended as soon as Europeans arrived in the area. When excavations in the early part of the twentieth century unearthed evidence to the contrary—pottery and glass from the 1800s, for example—the artifacts were dismissed as anomalies, evidence of a precontact site with early American settlers living on top. “But why couldn’t that be Native people living on that site?” Panich wondered.

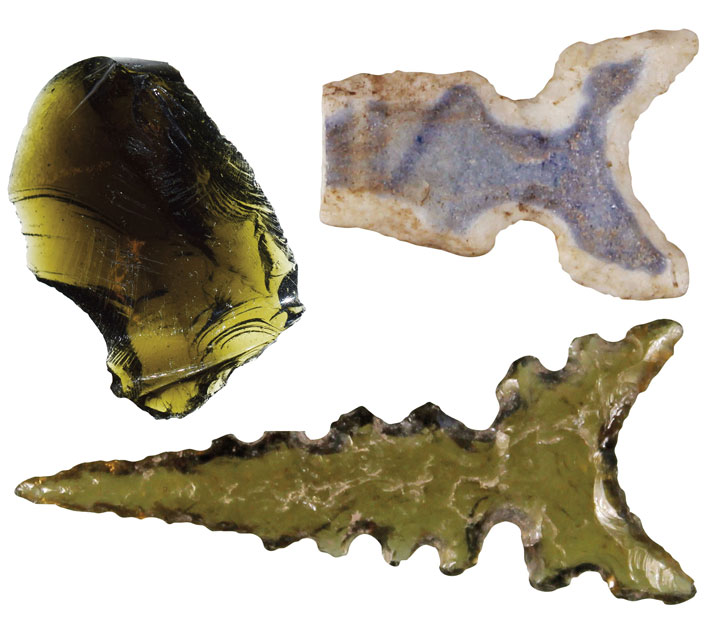

Over two summers, Schneider’s team conducted magnetometry and electrical resistivity surveys looking for evidence of houses or hearths on the shell mounds at China Camp. With permission from the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, whose ancestral land included the China Camp mounds, Schneider excavated hearths and collected sediment samples from the site, adding evidence to boxes full of finds gathered at the site in the late 1940s. And indeed, when shells, charcoal, basketry fragments, and other China Camp artifacts were radiocarbon dated, the results showed that people occupied the mounds from 1440 well into the 1800s. They also continued to use traditional flint, obsidian, and other stone tools despite the fact that metal became common at nearby missions. It is clear that people maintained their traditions even when European imports became available.

Analysis of the plant remains and animal bones showed that people living atop the China Camp mounds subsisted on an abundant array of seafood and birds, along with deer, pronghorn, sea otters, and harbor seals, even as nearby missions introduced European-style agriculture and cattle herding to the region. “It turns out we didn’t need the Franciscans to tell us where to live and what to eat,” Schneider says.

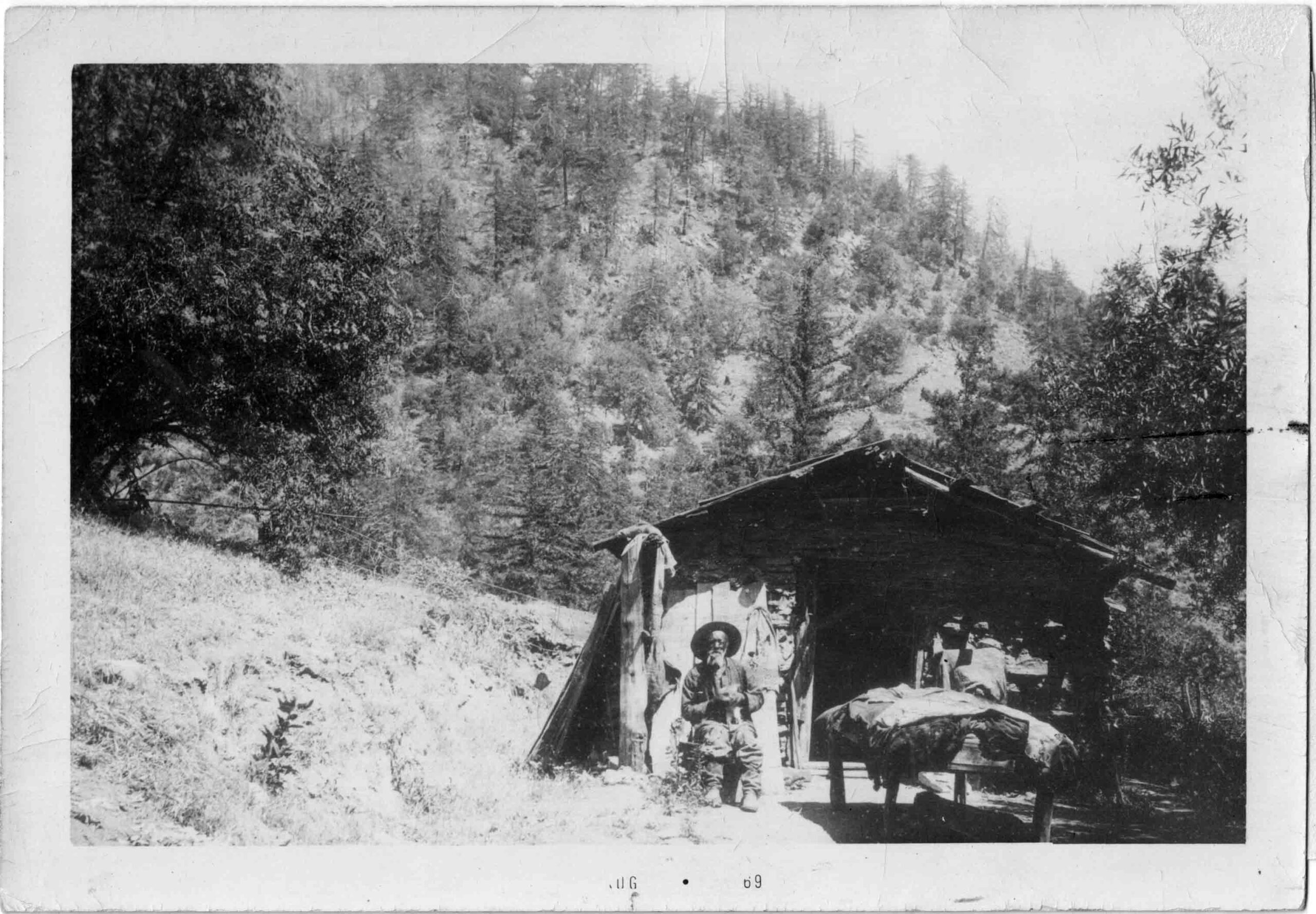

The finds at China Camp prompted Schneider and Panich to look for other evidence that Indigenous communities persisted beyond the mission period. In 2015 and 2016 they excavated at a trading post called Toms Point—founded by a white settler in the early 1840s—on the Pacific coast north of San Francisco. To keep their impact on the land as minimal as possible, the team used ground-penetrating radar to identify the heart of the settlement. They then collected material from the surface and from a handful of small test excavation pits.

Radiocarbon dating showed that the site was occupied beginning 5,000 years ago and continuing through the mission period and beyond, contradicting the idea that the missions had rounded up or killed everyone living in the region. And just as at China Camp, the nature of the artifacts at Toms Point provided evidence that Native culture was far from extinct. Well into the 1840s, nearly 60 years after Spanish missionaries first started pushing Coast Miwok people into missions, and just a few years before California became a state, people were crafting discarded glass bottles into cutting implements and metal spikes into fishhooks while continuing to make stone tools. “We can see that these technological traditions persisted,” Panich says. “The assumption always was that metal tools were better than stone and had replaced them as soon as they were introduced. But people clearly didn’t give stone tools up.”

More recently, Panich’s focus has turned back to the missions themselves. Because of construction work to expand Santa Clara’s campus, archaeologists were able to finally take a close look at the part of the mission where Indigenous people lived. Their findings showed that people there were applying traditional techniques to new materials in the shadow of the mission church. For example, there, too, they repurposed bottle glass and porcelain sherds to make arrow points. “People had access to new materials,” Panich says, “but were using them as ironic commentary: ‘Here’s your trash and we’re going to make something to shoot you with.’”

During the 2012 preconstruction excavations, archaeologists unearthed thousands of mission-era obsidian flakes, more stone tools than archaeologists had collected in nearly a century of Bay Area archaeology. Along with hundreds of other artifacts from the dig, these are now stored in a campus warehouse and at the university’s Community Heritage Lab, an archaeology facility housed in a 170-year-old building. Opening a box full of black flakes stored in plastic bags, Panich explains that by analyzing chemicals in the volcanic glass, archaeologists can trace the tools back to their source and show that, alongside the tool technology itself, precontact trade networks persisted into the mission period. “Trade networks didn’t just disappear,” Panich says. “Native people were still able to obtain these materials.” At Santa Clara, he found obsidian cutting tools from the height of the mission period that were sourced from the Napa Valley, nearly 100 miles to the north, and even from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains, nearly 300 miles away.

The excavations also revealed evidence that the Ohlone and other Indigenous people continued to practice traditional religious beliefs at the missions. Pits containing burned shell beads, boot spurs, and other personal possessions—“high-status stuff,” Panich says—showed that mourning ceremonies that included such offerings continued even after Catholic friars banned them. “People were practicing traditional burial rites,” Panich says. “It makes you wonder how successful the missions really were at converting people.”

Schneider and Panich hope that archaeological work at the missions and at Native sites in the surrounding landscape will shift how people talk about California’s Indigenous community. So do many other California Native Americans. On a windy day in the summer of 2021, Kanyon Sayers-Roods stood outside the locked metal gate of Mission San Juan Bautista, about 50 miles south of Santa Clara. Sayers-Roods, who also goes by CoyoteWoman, is Ohlone and Chumash and a member of the Indian Canyon community. Her ancestors lived in the fertile San Juan Valley for millennia, even after the missions at San Juan Bautista and nearby Santa Cruz were founded in 1797. “It’s easy to say, ‘They were here, they used to do this,’” Sayers-Roods says. “But we need to talk about Native peoples as present, not past.”

San Juan Bautista is one of the state’s best preserved missions. It was a destination for generations of Bay Area fourth graders, who learned about the mission system as part of the state history curriculum. Until 2017, building replicas of San Juan Bautista and other missions out of Popsicle sticks or sugar cubes was an elementary school rite of passage, along with a field trip to one of the surviving mission churches. Those tours typically skimmed over the toll the missions took on California’s Indigenous population, such as the 19,000 Mutsun Ohlone and other California Native Americans whose deaths are recorded in San Juan Bautista’s mission archives. “The stories that have been told at San Juan Bautista are very one-sided,” says California State Parks archaeologist Zackary Moskowitz.

Today, San Juan Bautista is a patchwork. Parts of the former mission property are owned by the state of California and managed by California State Parks. The mission church itself belongs to the Catholic Church, and the land around it to private owners. In 2021, scans of an empty lot not far from the central mission complex detected the circular outlines of Native-style houses next to one of the mission’s adobe barracks blocks. “We found the indentation of the floor surface and postholes,” says GeorgeAnn DeAntoni, an archaeobotanist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. This type of evidence is uncommon, because the walls of the traditional tule round houses aren’t usually preserved in the archaeological record.

The tule houses, which were burned regularly to eliminate pests and then rebuilt with abundant local materials, offered healthier living spaces than the crowded Spanish-style adobe houses arrayed near the mission’s church. In 2015, another scan revealed an unexcavated adobe barracks with 50 small rooms. Schneider says it may have housed hundreds of people in crowded conditions that made it easy for disease to spread. “As much as the Franciscan padres tried to get people inside adobe barracks, the people chose not to live in them,” Schneider says. “They kept building tule homes at the missions.”

The houses and hearths offer an opportunity to explore plant remains to learn what Ohlone and others at the mission were growing and eating and whether they continued to use plants for food, medicine, and construction materials in traditional ways. With the permission of California State Parks and participation from the Amah Mutsun, DeAntoni plans to analyze samples from hearths at the center of several pit houses. She hopes the results will also show how the missions affected the environment. “The knowledge you gain from one of these small tule houses could tell you a lot about how people were interacting with the landscape,” she says. DeAntoni suspects that, over time, traditional lifestyles became harder to maintain as oak forests were cleared for cattle and dietary mainstays such as acorns became harder to find. That scarcity pressured Indigenous communities to move into missions or further adapt to stay alive.

DeAntoni’s planned project represents a first-of-its-kind effort at San Juan Bautista. Because many native California plants have seeds just a few hundredths of an inch across and are thus difficult to spot, previous excavators there didn’t collect small plant remains, leaving a gap in what is known about the site. From letters written by Spanish friars, researchers know that, despite efforts to introduce European crops, the Native population maintained aspects of their traditional diet, something priests recorded disdainfully in their letters. “They have in their little cabins an abundance of acorns and wild seeds, their ancient food,” a friar at San Juan Bautista wrote in 1814. “We Missionary Fathers care for their planting and harvesting. When this does not suffice, the neophytes return to the mountains in search of wild seeds.” “The fundamental assumption in academia was the missions come in, build walls, and Indigenous history ends,” Schneider says. “In reality, these were porous spaces, and traditional cultural and ecological knowledge outlasted the missions. Native people arrived, they often departed, they learned from these experiences, and their culture survived.”

Representatives of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band and Indian Canyon hope that archaeological excavations will foster deeper links to their past while helping efforts to reinvigorate their culture. Across the street from the gate of San Juan Bautista’s mission complex is a different kind of monument. In a corner lot shaded by live oak trees, the Mutsun Ohlone maintain a garden full of native plants. Each one is labeled in both Mutsun and English: hiisen, or California mugwort, and torow, or soap plant. “I’m vehemently against the destructive analysis of ancestral human remains, but I’m excited to learn from plant and animal remains,” says Sayers-Roods. “Archaeologists can learn from Indigenous community members, and Indigenous community members can learn from archaeologists.”