The Nile was the lifeblood of ancient Egypt, and its inundation was the pivotal annual event in Egyptian civilization. Every summer, between May and September, the river gradually swelled until it overflowed its banks and flooded the surrounding plains. When the waters receded, they left behind layers of fertile deposits that were essential for growing crops to feed the realm. However, the floodwaters fluctuated from year to year, and when they fell short of or surpassed the optimal level, dire consequences followed. An insufficient flood meant that the water did not reach all arable land, often resulting in famine and civil unrest. On the other hand, overflooding could destroy infrastructure, wipe out livestock, and breed pestilence and disease.

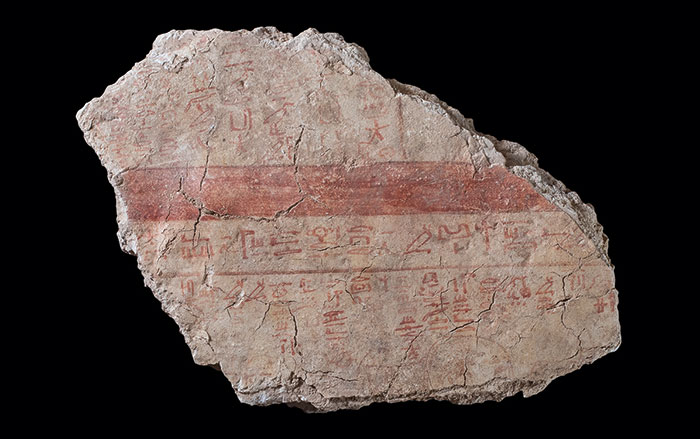

To gauge and help forecast each year’s flood, Egyptians developed a device known as a nilometer. “Nilometers evolved as a sacred means of monitoring, communicating, and experiencing variations in the behavior of the river,” says Nottingham Trent University archaeologist Jay Silverstein. Nilometers were once located up and down the Nile, and while archaeological evidence of the earliest devices is scarce, inscriptions mentioning nilometers date back 5,000 years. The most recently discovered example was found in the Nile Delta at the Greco-Roman city of Thmuis, modern-day Tell Timai, and was constructed in the third century B.C.

Nilometers were built in a variety of shapes and styles and were located next to the river or linked to it through channels or conduits. The main feature of most nilometers, including the one at Thmuis, was a holding tank or well that was fed by the Nile’s waters. As the river rose and fell, so did the water level within the nilometer. Some nilometer complexes housed a staircase that provided easy access for those charged with measuring the water. Others included a column with evenly spaced marks that acted like a giant ruler indicating the river’s height. During the flood season, priests monitored water levels daily to help predict how the flood was progressing. “As the Nile approached its optimal level,” Silverstein says, “the priests would watch carefully and, when it achieved that point, there would be great festivities and floodgates to fields would be opened.”