The Lendbreen ice patch is located high in the mountains of southern Norway, in a range that runs like a spine through Scandinavia. In the 1800s, the area was dubbed the Jotunheim Mountains, or the home of the jötnar, the rock and frost giants of Norse mythology. Its peaks are the highest in northern Europe and are snowbound year-round.

The summer of 2006 was unusually warm in the Jotunheim Mountains, with temperatures high enough to melt not just the previous winter’s snow, but also layers of ice beneath, representing thousands of past winters. One day, a woodworker and hobby archaeologist from the nearby town of Lom, in Oppland County, came across a well-preserved leather shoe while hiking near Lendbreen. He carried it back to town and turned it over to curators at the Norwegian Mountain Museum. When archaeologists examined it, they were stunned. It wasn’t a modern shoe, but one that was last worn in the Bronze Age, some 3,400 years ago.

It turned out that the conditions at Lendbreen had long been perfect for preserving such ancient artifacts. Objects left on the surface ages ago were covered with snow that eventually compacted to ice, shielding them from decay and disturbance for thousands of years. But the summer of 2006 was warm enough to melt this protective shell, exposing the shoe. The archaeologists wondered, could there be more ancient artifacts hidden in various ice patches? Perhaps more importantly, were some of these artifacts now at risk from the elements?

The fortuitous discovery of the Bronze Age shoe helped the local heritage management office push for an organized rescue program to locate, assess, and search dozens of sites in the mountains of Oppland. It’s an effort that combines archaeology with high-tech mapping, glaciology, climate science, and history. When conditions are right, it’s as simple as picking the past up off the ground. “The ice is a time machine,” says Lars Pilö, an archaeologist who works for the Oppland County council. “When you’re really lucky, the artifacts are exposed for the first time since they were lost.”

In Scandinavia and beyond, the booming field of glacier and ice patch archaeology represents both an opportunity and a crisis. On one hand, it exposes artifacts and sites that have been preserved in ice for millennia, offering archaeologists a chance to study them. On the other hand, from the moment the ice at such sites melts, the pressure to find, document, and conserve the exposed artifacts is tremendous. “The next 50 years will be decisive,” says Albert Hafner, an archaeologist at the University of Bern who has excavated melting sites in the Alps. “If you don’t do it now they will be lost.”

It’s physically demanding, highly unpredictable work that sometimes involves sitting in tents for days through rain, snow, and high winds, until it is safe to work on the steeply pitched slopes. In summer 2012, I followed Pilö and two archaeologists to the Lendbreen ice patch to get a sense of the challenges involved.

There’s no way to get to Lendbreen except on foot (or by helicopter, though that is prohibitively expensive). When we talked on the phone weeks before, Pilö asked for reassurance that I was “fit” before he agreed to take me along. At the trailhead, I began to understand his concern. From an unpaved road in the valley below, we’d gain 3,600 feet in a hike of under four miles, scrambling along gravel-strewn switchbacks at grades of more than 20 percent.

A local farmer had gone ahead, leading a pair of horses carrying the heaviest gear—survey equipment, stoves, and camping fuel. But each of us still carried a backpack loaded with food, tents, more survey gear, and extra clothes. Elling Utvik Wammer, a sturdy-looking young Norwegian archaeologist with a beard and a big smile, seemed as heavily loaded as one of the horses, yet I struggled to keep pace with him. The last stretch crossed a few hundred yards of snow; it was like going the wrong way up a ski slope. Underneath, I could hear the rush of a hidden stream, a reminder of the melting ice above.

Finally, we made it up and over the last stretch, and I got my first glimpse of Lendbreen. The whole climb up I’d been picturing something massive and glacier-like, but the reality was different. The site looked more like a dirty patch of snow a few hundred yards across, sitting on a steep, rocky incline. Meltwater fed a tiny, dark blue lake at the base of the slope. Moss was the only green to be seen.

Not long after we pitched our “Everest-rated” tents next to the lake, the wind picked up. It moaned loudly around the walls of the tent all night. Dawn revealed a miserable scene: Heavy fog obscured the side of the mountain completely, and a mix of sleet and wet snow blew nearly horizontally. It was too dangerous to ascend farther that day.

We tried to make the best of it, and sat in a tent as Pilö explained his work and what it means. In Norway, ancient artifacts have been emerging from glaciers and ice patches since the 1930s. Usually the finds amounted to little more than an arrow here or a spear there—isolated misfires lost in the snow in times past. But since that first prehistoric shoe turned up in 2006, archaeologists have found more than 1,600 artifacts in Oppland County alone, sometimes hundreds at a time. Pilö said Oppland’s finds represent more than half the total number found so far in ice patches worldwide. By comparison, the Alps, another hotbed of melting ice, have yielded about 850 objects in recent years.

Pilö told me about the previous year’s trip to Lendbreen, at the end of 2011’s unusually warm summer. He had brought a team of nearly a dozen up to the ice patch. On their last day at the site, as they picked their way across freshly exposed rock in heavy fog, they found a sodden tunic, or kyrtel, woven from heavy wool. A few yards farther on, more cloth objects and wet leather were lying on the rocks.

Then, Pilö recalled, the fog lifted a bit. The view was breathtaking. “We were in this hollow with hundreds of artifacts. The whole place was just littered with leather, textiles, wood, and animal dung. It was a fantastic experience, one of the best I’ve had in my career.”

As Pilö and others analyzed the artifacts, they realized that almost all were related to elaborately organized reindeer hunting. In the summer, reindeer crowd together on the glaciers and ice patches of the Norwegian highlands. The animals have a strong aversion to botflies, parasites that lay eggs under the skin of large mammals, so they spend summer days on the ice, safe from the flies. That predictable behavior made the reindeer tempting targets for ancient hunters.

Melting ice at Lendbreen has revealed evidence of one of their common hunting techniques. The archaeologists have found hundreds of “scare sticks,” wooden stakes with flat wooden shingles attached to them by string so the shingles blow around in the wind. The sticks were planted in the snow in long rows. According to an eighteenth-century report from a Danish missionary in Greenland, the unfamiliar moving objects unsettled the reindeer just enough—without spooking them—to guide them toward stone hunting blinds, where hunters waited with bows or spears. “They had to be quite still in the blinds—the scaring sticks only work if the reindeer aren’t stressed,” Pilö said. In 2009, while working on another ice patch, Pilö’s team spooked a herd of domesticated reindeer and watched them charge through a line of bamboo survey poles topped with strips of tape, an accidental confirmation of the historical accounts.

The hunts took place regularly for thousands of years, essentially unchanged until the advent of firearms. “Hunting on your own with a bow and arrow is extremely difficult,” Pilö said. “Reindeer are very shy, and it’s difficult to hit a running reindeer at 100 meters. It was easy to lose equipment, which was quite precious.”

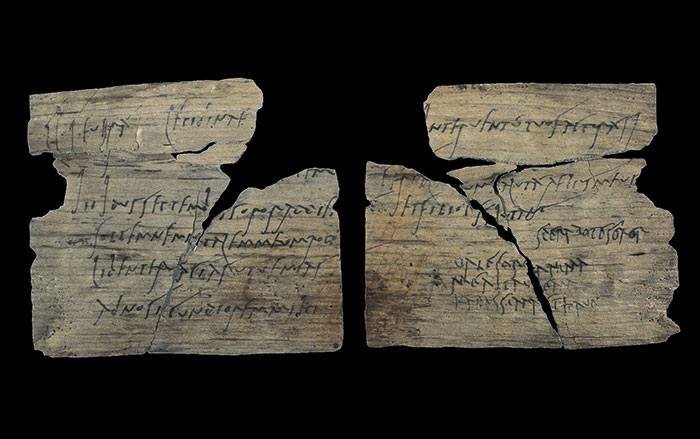

The hunting gear found atop the ice patch ranges from scare sticks and arrows to a spear and even a crossbow bolt. The ice patch at Lendbreen also straddles a ridge linking two valleys. Moss-covered rock cairns nearly as tall as a man, along with jagged stones placed upright, mark a trail across the pass that people and their livestock may have used for centuries. The team found plenty of evidence of high-mountain traffic, from that Bronze Age shoe to a Viking mitten, an elaborately carved walking stick, fragments of a ski, and copious horse and sheep dung.

All the artifacts along the pass were lost and frozen some time between A.D. 300 and 1200, but age can be impossible to tell by location alone. Unlike a typical archaeological site, where the oldest finds are on the bottom and the latest artifacts are on the top, Lendbreen is “flat”—when the ice melts, artifacts from separate layers wash down and end up in one layer together. “They were probably lost or dumped in the snow all during this period, but are now found together on the ground,” Pilö said. Though they were all released from the ice during a single summer, radiocarbon dating shows they were once trapped across centuries of accumulated ice.

The reason for their emergence together is as clear as melted snow. The world is getting warmer, a phenomenon an overwhelming majority of scientists blame on a sharp increase in the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. The consequences of global warming are vividly displayed in the world’s icier regions. An Oppland ice patch called Juvfonne, which sits near the bottom of a glacier that Norwegians ski on year-round, was 65 feet thick when Pilö and his colleagues started working there in 2009. In the last four years, it has lost 13 feet of ice.

“It’s very impressive when you can say this melting ice is 5,000 years old, and this is the only moment in the last 7,000 years that the ice has been retreating,” says Hafner. “Ice is the most emotional way to show climate change.” Lendbreen hasn’t melted quite so much, but satellite photos reveal that the 2011 warm spell caused the ice to retreat up to 20 yards in some places.

On our last day at the site, I was awakened before dawn by shouting outside the tent. The wind hadn’t slackened all night, and two of the tents had finally given way, aluminum poles crumpling under the assault. Wammer and Julian Martinsen, the third member of the survey team, crowded into the two still-standing shelters for a few more hours of sleep. When the sun finally rose, the storm seemed to have passed. There was still a stiff breeze, but the clouds had parted to reveal patches of blue sky. Pilö decided it was safe enough to hike up to the ice patch itself.

Lendbreen, as I saw from below, is no glacier. It is tempting to think of all these melting sites as glaciers, and the field as “glacier archaeology,” but that is a bit of a misnomer. Ice patches like Lendbreen are more conducive to the preservation of ancient artifacts. Glaciers are like rivers of ice. Pushed by accumulating snow and ice at higher altitudes, they flow downhill a few dozen feet a year. Glaciers move, glaciers grind, glaciers pick up boulders the size of SUVs and deposit them miles away. Imagine a slow-motion washing machine filled with rocks. Archaeological material rarely survives inside a glacier for more than a century, and it invariably ends up far from where it was first lost. “Glaciers aren’t suitable for preserving prehistoric items—they’re always moving,” says Hafner.

Ice patches, however, are stationary accumulations of snow and ice, often in isolated basins or on shady mountainsides. Centuries of snowfall accumulate and freeze, creating blocks of ice that can be 65 feet thick or more. Artifacts lost or left in the snow atop an ice patch don’t get churned as they would in a glacier. They are not only perfectly preserved by the ice, but they may also lie close to where they were left or dropped thousands of years ago. “The remains from hunts are preserved on-site,” Pilö said. “[Projectiles] are sometimes still lying in the direction they were originally shot, so you can see the direction the hunter was facing.” Even iron corrodes very slowly in ice patch conditions. Arrowheads have been discovered sitting on bare rock, easily spotted thanks to trickles of rusty meltwater.

Among the items preserved by the ice, fabric and leather are the most remarkable—and the most fragile. Wood artifacts may last a few years once they melt out of the ice, but for these items, the clock runs out much faster. “You really have to be there when the leather comes out, because it goes away very quickly,” Pilö said. “You have a week or less to recover leather—it dries out, becomes light and brittle, and blows away.”

The discovery of the kyrtel in 2011 was just such a stroke of luck. Made of lamb’s wool and big enough to fit someone about five foot nine, the garment is 1,700 years old. While it is easy to explain how arrows, a walking stick, and even a shoe were lost in this ice patch, why the garment was left behind is a mystery. As I looked up to where the kyrtel was discovered, I wore a lined parka and three pairs of pants. It was hard to imagine why someone would have taken his or her warm wool top off up here. Then Pilö reminded me about the latter stages of hypothermia, which, grimly and counterintuitively, include a feeling of intense warmth. “Maybe they started to feel the last stages of hypothermia and removed their clothing,” Pilö said. I shivered.

As the team began to work its way uphill to the ice patch, I quickly fell behind. Pilö, Wammer, and Martinsen picked nimbly along, but the rocks— sharp enough to cut through thick leather hiking boots—shift unpredictably underfoot and slow me down.

The team spread out in a loose line, each one a few yards apart, and began walking, heads down. To narrow their search area in vast mountainsides covered with jagged rock, Pilö and his team look for spots not covered in gray-green scales of lichen. Lichen grows slowly, so rocks without it are likely to have been exposed relatively recently—from a few days to a few decades before.

“It’s such a vast landscape, if you’re not right on top of [artifacts] you don’t see them,” Pilö said, eyes on the ground. At least it’s not hard to figure out what’s an artifact: Nothing grows here besides lichen and hardy moss, so the smallest fragment of wood or bone is certain evidence of human activity. Using a GPS device mounted on a long carbon-fiber pole, the archaeologists documented locations of artifacts and where they searched, so they could pick up where they left off if there is another warm summer soon. “We wanted to get control of the situation so in years of heavy melting we can go monitor the sites,” Pilö said. “We have to revisit sites and collect artifacts as the ice disappears. That work is ongoing, and easier to deal with.”

Bamboo poles topped with black tape marked areas they had searched. More poles, with blue tape, marked finds. At the end of the day, they would work their way back and gather what they had found. It was slow going, and for an hour or so there was nothing to find but scraps of reindeer antler and fragments of wood.

Suddenly there was a shout and a wave. Martinsen had spotted what looked like a sun-bleached wood rod nestled between two boulders. Pilö picked his way down the slope. After photographing it and recording its location, he bent to examine what was once a crossbow bolt, six inches long. “If this is lying where it fell, they would have been shooting from over there,” he said, gesturing downhill. Though lots of arrows and scare sticks had been found, this was the first crossbow bolt they’d discovered, a sign that hunting was still going on in the late Middle Ages, when the technology was first used for hunting there.

By lunchtime, the team had also found a few scare sticks and two pieces of squared-off wood that later analysis would identify as an early ski. Wammer and Martinsen carefully wrapped the pieces of wood in plastic and cardboard to protect them on the descent. Later they would be taken to a lab for study and preservation. Within weeks, weather would make Lendbreen inhospitable for fieldwork. An unusually cold winter meant the region got very little snow, making the ice patch even more vulnerable to a future warm spell. As the summer of 2013 approached, Pilö watched the weather to see if more melting—and another trip to the ice patch—would happen. “We are preparing for a major melting incident,” he said in June 2013. “It would be foolish not to.”

Glacier and ice patch archaeology has boomed in recent decades, with places from Norway to the Northern Territories of Canada yielding artifacts and more. The famous Ötzi, a 5,300-year-old cadaver found by hikers in 1991, was preserved in an ice patch connected to the Ötztal glacier on the Italian-Austrian border. Hundreds of objects have been found in the Swiss Alps in the last decade, and Canadian archaeologists have begun identifying melting ice patches using helicopters, usually by the sight of centuries’ worth of preserved caribou dung. Last year, the journal Arctic devoted an entire issue to “The Archaeology and Paleoecology of Alpine Ice Patches: A Global Perspective.”

Ancient people in Scandinavia and Canada, though widely separated by distance, appear to have used glaciers and ice patches in the same way—as summer hunting grounds for large mammals—and therefore left remarkably similar collections of artifacts behind. In the Northern Territories, archaeologist Greg Hare has, by helicopter, found 24 ice patches with cultural material—objects used to hunt the once-abundant caribou. “If we saw caribou dung [near an ice patch], we would land and walk the edge looking for artifacts,” Hare says. “It’s the same motives getting people up in the mountains. There they’re hunting for reindeer, and here they’re hunting for caribou.” Among the items his team has discovered are arrows, spear-throwers, and barbed arrowheads made of caribou antler.

But the two regions also have differences—vital reminders of the complex future archaeologists in these parts of the world will face. When Hare first started surveying melting ice patches in the 1990s, they were disappearing so fast he assumed they’d all be gone within a decade. However, parts of northern Canada are actually seeing more snow and ice accumulate each winter, highlighting the unpredictability of global warming’s local effects.

As the world warms, more moisture will likely evaporate into the atmosphere, resulting in heavier snowfalls at northern latitudes. Instead of shrinking, many Canadian ice patches are actually growing. “The Yukon is becoming warmer, but that means we’re getting more snow and ice, at least in the short term,” Hare says. “Depending on where you are in the world, there’s a big difference in the amount of melting and potential for glaciers [and ice patches] to disappear.”

But in the end, few places will be immune to the slow rise in global temperatures. There’s a depressing sense of the inevitability of this, even when trudging across fields of snow and ice in late August. Climate scientists estimate that if the world continues warming at the same rate, 90 percent of its glaciers will be gone by 2100. Ice patches face a similar fate. “They’ve been here for 6,000 years, so it’s incredible to think they’ll be gone in 100,” said Pilö.