Although archaeologists have excavated 500,000 cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamian sites over the last two centuries, about half of these texts now in museums around the world haven’t been thoroughly studied or published. It is only by applying new technology that scholars will be able to even make a dent in this huge number. This year’s success story is a newly deciphered, previously unknown hymn extolling Babylon as the first city in existence. The hymn also praises Babylon’s citizens and their patron deity, Marduk. “It’s a text that tries to indoctrinate you in the love of your city,” says Assyriologist Enrique Jiménez of Ludwig Maximilian University.

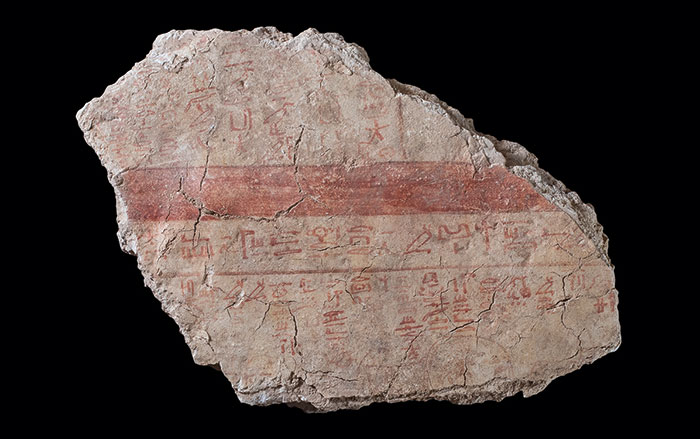

Jiménez and Assyriologist Anmar Fadhil of the University of Baghdad studied a large section of a tablet containing part of the hymn held by the Iraq Museum that was excavated in the 1980s from the library in the ancient city of Sippar. After transliterating the text, they used artificial intelligence models to search for overlaps with other tablets. The researchers identified 30 fragments from 20 different tablets containing sections of the hymn. Without the assistance of artificial intelligence, this process would have taken years, if not decades—or been impossible. “In the past 150 years of cuneiform studies, researchers found around 6,000 places where tablet fragments joined,” Jiménez says. “We’ve found 1,500 in the last five years.”

Jiménez and Fadhil have thus far recovered about two-thirds of the hymn, which they estimate originally totaled around 250 lines, and which was likely composed in the second half of the second millennium b.c. In addition to the panegyric to Babylon, the hymn contains many previously unknown pieces of information, such as an enumeration of the duties of Babylonian priestesses, who, according to the text, also served as midwives. In contrast to most Mesopotamian literature, the king is not a central figure in the hymn. “It’s interesting that the Babylonians present themselves as a group, and the perspective of the king isn’t there,” says Jiménez. “They say, ‘We are older than any king that may come. Kings come and go, but the Babylonians will always stay.’ That’s a very cool thing.”