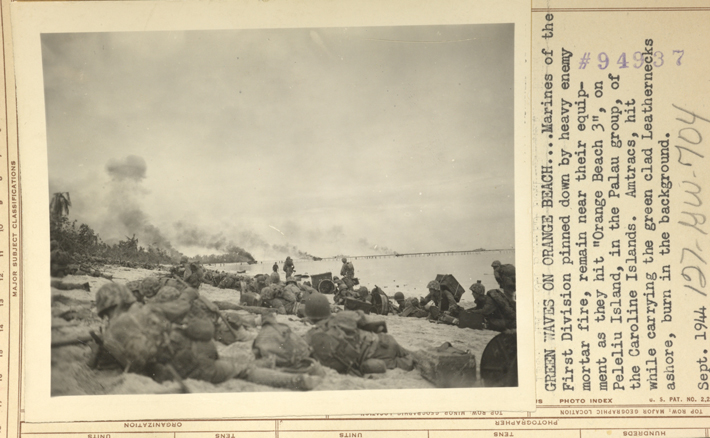

On the morning of September 15, 1944, some 18,000 U.S. marines from the First Division invaded the tiny Western Pacific island of Peleliu, at the south end of the Palau archipelago. Nearly three years after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Americans and their allies were on the offensive, pushing their way across the Pacific. This campaign involved millions of U.S. military personnel, and unfolded over thousands of miles of ocean. Many of the key battles were fought over Pacific islands such as Guadalcanal and Guam, both of which the Americans captured after fierce fighting. They then established bases on these islands as they advanced closer and closer to Japan. By fall 1944, the Americans were eager to begin a long-planned invasion of the Japanese-occupied Philippines. They saw Peleliu, which lies 500 miles east of the Philippines and had excellent harbors and a Japanese-constructed airfield, as a valuable launching pad.

Shaped like a lobster claw, Peleliu measures at most five miles long by two miles wide. Because the island is so small, Marine Corps Major General William Rupertus predicted it would be subdued in a few days, despite the 11,000 Japanese troops and at least 3,000 Korean and Okinawan forced laborers ready to defend it. In fact, the battle, code-named Operation Stalemate II, ended up dragging on for more than two months. The marines were reinforced, and later relieved, by 11,000 soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 81st Infantry Division. Over the course of the battle, the Americans unleashed an astounding barrage of munitions. Navy ships anchored offshore fired almost 6,000 tons of shells. Navy and marine aircraft dropped at least 800 tons of bombs. In their month on the island, the marines expended almost 16 million rounds of ammunition, including 116,000 hand grenades. The toll on the Americans was great—at least 1,600 died on Peleliu. For the Japanese, the toll was catastrophic. Fewer than 100 soldiers survived. And, in the end, it was all for nothing. The invasion of the Philippines started on October 20, even as the battle for Peleliu raged on.

“Peleliu was the first real slugfest where the Japanese consciously hung back to try to cause the maximum number of casualties for the Americans so they would think twice about invading an island like that again,” says Rick Knecht, an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen who previously served as an ethnographer with Palau’s Bureau of Arts and Culture. “But the Americans had enough resources to keep throwing in more people and materiel. It was just plain ugly, and it dehumanized everyone involved.”

Peleliu is now barely remembered by comparison with more strategically consequential World War II engagements such as Guadalcanal and Iwo Jima, but its battlefield is the best preserved of the entire Pacific Theater. Since the war’s end, the island’s residents have generally avoided the areas where combat was most intense, which were left littered with human remains and unexploded munitions, and which are hilly and obscured by thick foliage. (See “Peleliu’s Battle.”) For Knecht and a team of fellow archaeologists who have carried out two surveys of the battlefield—accompanied by demining experts who disabled and removed dangerous explosives—Peleliu has offered a rare opportunity to document the experience of soldiers on the front lines of the battle for the Pacific. “There are skulls and helmets and all the soldiers’ stuff lying there just as it was left after the battle,” says Knecht. “It’s gruesome and horrible, but war is gruesome and horrible. Short of going into combat, Peleliu is probably the closest experience to being on a World War II battlefield.”

The project, which was initiated by Palau’s Bureau of Arts and Culture and carried out in cooperation with government representatives as well as traditional chiefs on Peleliu, has explored hundreds of sites on the island. Several stand out as illustrative of the battle’s three phases: the American invasion and struggle to gain a foothold in the island’s low-lying western plain, the drawn-out period in which the Americans slowly ground away at the Japanese defenses in the island’s mountainous north, and the point when the Japanese leaders recognized their cause was lost. Archaeologists have also found personal items that, in some cases, they have been able to link to individual soldiers by name. And, they uncovered an inscription that offers insight into the mindset of young men willing to fight to the last.

The Japanese had responded to previous Pacific island invasions with large-scale, suicidal charges that, although ultimately doomed, led to high casualty rates for the Americans. On Peleliu, Imperial Japanese Army Colonel Kunio Nakagawa pioneered a new strategy that involved setting his defenses in the Omleblochel Mountains, a series of ridges that line the island’s northeastern peninsula. Although these mountains are at most several hundred feet high, they feature steep cliffs and deep ravines that make them extremely hard to penetrate. In the months before the invasion, the Japanese had transformed this difficult terrain into a fortress, using hundreds of natural and artificial caves, along with connecting tunnels, as hideouts. This strategy made the battle very different from those that had preceded it, and went on to serve as a model for the Japanese defense of Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

When the marines made landfall on a pair of beaches on Peleliu’s west coast code-named White and Orange, they were met with a fusillade of artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire from Japanese emplacements flanking the assault beaches. Additional fire rained down from positions the Japanese had established in the island’s southernmost hills above the beaches and the airfield, which was the Americans’ primary objective. The day after the invasion, a full regiment of marines charged across the exposed airfield. Although they managed to capture it with relatively few casualties, for the infantrymen involved, the ordeal was harrowing. Marine Corporal Eugene Sledge describes it in his memoir, With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa, as his worst combat experience of the entire war. “Chunks of blasted coral stung my face and hands while steel fragments spattered down on the hard rock like hail on a city street. Everywhere shells flashed like giant firecrackers,” he writes. “...To be shelled by massed artillery and mortars is absolutely terrifying, but to be shelled in the open is terror compounded beyond the belief of anyone who hasn’t experienced it.”

EXPAND

Peleliu’s Battle

In the years since the Battle of Peleliu, Palauans have largely avoided the ridges and caves where the worst fighting took place, wary of chancing upon the ubiquitous unexploded ordnance and disturbing the human remains that were left at the end of the war. But these areas were once very much a part of Palauan life. In their surveys of the battlefield, archaeologists led by Rick Knecht of the University of Aberdeen and Neil Price of Uppsala University have found Palauan pottery likely dating back many centuries near every natural cave used by the Japanese during the battle, as well as large prehistoric shell middens in sections of remote jungle. “The battle was fought on a Palauan cultural landscape,” says Knecht.

Peleliu, along with the rest of the Palauan archipelago, was settled at least 3,000 years ago by migrants from islands in Southeast Asia. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, Palau was colonized by Spain, then Germany, and, in 1914, by Japan. In preparation for war, two of Peleliu’s five traditional villages were razed to make way for an airfield constructed by the Japanese in the late 1930s. The Japanese used forced Palauan labor to dig many of the caves in which they would hide during the battle, but evacuated the island’s natives before the Americans invaded. Peleliu’s remaining three villages were destroyed in the battle, along with the island’s previously abundant vegetation. “When people returned [in 1946], they found their island devoid of anything green,” says Sunny Ngirmang, director of Palau’s Bureau of Cultural and Historical Preservation. “It was all white limestone, and you could see from one side of the island to the other—that’s how bare it was.”

Arguably even more damaging for the returning islanders than the destruction of their villages and environment was the loss of almost all of the island’s olangch—natural or constructed markers such as stones, trees, and burial sites that served as prompts to the recollection of important memories and stories. The battle had effectively erased thousands of years of the island’s history. Nonetheless, the Palauans have come to see themselves as custodians of the more recent historical record left behind by the battle. “The war was destructive to people who had no say about it whatsoever,” says Ngirmang, “but its legacy remains in the hearts of those who were affected. Their stories have been passed on from generation to generation and now it has become a part of our own history.”

During the battle, much of the island was completely denuded of vegetation by intensive bombardment from air, sea, and ground. What was left was a moonscape of jagged white limestone that tore up the soldiers’ boots and uniforms, abraded their skin, and mercilessly reflected the tropical sun, sending temperatures soaring as high as 115°F. In the decades since, the island has been reclaimed by dense jungle. Nonetheless, explains archaeologist Neil Price of Uppsala University, codirector of the project along with Knecht, “The airfield is easily recognizable. It’s mostly under jungle cover now, but you can still orient yourself, and the buildings that the Americans were attacking are still there, shot to pieces.”

One such building, between the airfield and White Beach, was a Japanese fuel-storage bunker that became the focus of an intense firefight in the battle’s early days, according to marine battalion reports and firsthand accounts of participants. After 35 marines were killed or wounded, their comrades, finding their ammunition useless against the bunker’s thick walls, called for supporting fire from the Navy fleet anchored offshore. A 14-inch shell slammed into the bunker, killing approximately 20 Japanese troops and leaving behind a giant hole that is still visible. “There are several reinforced structures that were shelled by the offshore fleet during the battle, with circular holes from direct hits that went through the walls,” says Price. “They’re enormous, and they penetrated multiple layers of concrete and all the rebar inside. You sort of stare at this and think, ‘What on earth was it like when that happened?’”

After a week or so of hard fighting, the marines had secured the airfield and other low-lying areas of Peleliu. They had also made inroads into the southern hills, and were no longer prey to Japanese bombardment from above. Then the real battle began. The Japanese had holed up in the hundreds of heavily armed, difficult-to-access caves they had prepared in the mountains. For the next two months, the Americans attacked with increasingly vicious means. First they dropped high explosives from aircraft and launched shells from battleships. Next they fired flamethrowers into cave openings, followed by grenades. Then they attacked the soldiers with machine guns and pistols. After that they called in napalm drops, waited for the jellied gasoline to seep into the porous rocky ground and the caves below, and then ignited it with phosphorous mortar bombs. When all else failed, they sealed the caves shut with bulldozers and dynamite, trapping Japanese soldiers inside.

During their surveys, Knecht and Price’s team visited nearly 200 caves that were used during the battle. Many contained charred bones and bits of uniforms, along with personal items such as chopsticks, sake bottles, eyeglasses, belt buckles, and buttons embossed with Imperial Japanese Navy insignia. To preserve Peleliu as a record of how the battle was experienced by soldiers on the ground, the researchers left everything on the island just as they had found it. “We had to take care not to let our minds dwell too long on what life was actually like inside the caves for the Japanese,” says Price. “It’s really quite indescribably awful and hopeless.” Even today, the caves are extremely hot, humid, airless places, pervaded with a lingering smell of burned hair. “These caves are horrible to be in even for a few minutes,” says Knecht. The stench must have been much, much worse during the battle, when groups of soldiers spent weeks on end cooped up alongside rotting food, human waste, and decomposing bodies. Knecht was initially surprised to find numerous used gas masks in the caves, given that gas was not employed in the battle. He came to realize Japanese soldiers had donned the masks in an attempt to block out the noxious odors.

Traces of engagements between the Americans and Japanese are ubiquitous in the caves, says Price. “There are sprays of bullet chips across the walls, the characteristic splinter patterns from grenades, and, most obviously, the flamethrower scorch marks across the walls and entrances.” In one cave in the southern ridges above the airfield, the team uncovered a particularly vivid tableau of a flamethrower attack. A gas mask was melted to the wall with bone fragments inside, suggesting it was being worn at the time of the attack. A burst canteen lay on the floor. “The water inside their canteens had turned to steam and exploded, popped like balloons from the inside,” says Knecht. “And there were human long bones driven into the ceiling and sides of the cave like big white spikes from the force of the explosions.” In the same cave, the archaeologists found a poignant reminder of the soldiers who died in the attack: a stack of melted 78-rpm phonograph records.

In addition to attacking the Japanese in their caves, the American troops on Peleliu skirmished with them for control of the high plateaus that dotted the mountains where the fighting was most intense. At one of these locations, at the northern end of the Omleblochel Mountains, amid the thick foliage that now covers it, researchers came upon a network of 20 defensive fighting positions set up by a U.S. Army platoon. The infantrymen would normally have dug foxholes, but the stony ground made this impossible. Instead, they piled up coral rocks to form curving parapets. According to historical reports, the Americans first seized this particular plateau just over a week after the invasion. In the days that followed, they repeatedly fought over the spot with the Japanese, and it changed hands several times.

As they explored the site, the archaeologists discovered striking evidence of one of these clashes. “In one rifle pit, you’ve got this perfectly preserved American grenade placed on the parapet ready for the infantryman to pull the pin and throw it over the side of the hill,” says project member Ben Raffield of Uppsala University. “A single rifle round had been carefully placed between the pieces of stone, as if to have it on hand for reloading.” On the slope beneath another rifle pit, the team found an undetonated Japanese grenade where it may have rolled after failing to reach its target. Next to it lay a full U.S. M1 rifle magazine. “You can imagine the infantryman at the top of the escarpment trying to reload his carbine during the firefight and dropping the magazine over the side,” says Raffield. Around 30 feet away, near yet another defensive position, a pile of rifle clips sat next to an American canteen, positioned as if they had been attached to a rifleman’s belt. The canteen bears a sharp, diagonal indentation, almost certainly produced by a cut from a saber blade during hand-to-hand combat. On the lower slopes of a hill in the island’s far north, the archaeologists found another American canteen, with the word “CORBI” crudely inscribed on its bottom. They determined it had belonged to a marine from the Bronx named Eliadoro T. Corbi, who had been wounded on Guadalcanal but survived Peleliu and, ultimately, the war, and died in 2011. “We were able to reach out to his family, which was quite emotional for them,” says Raffield. “There is a whole dimension to this archaeology that you just do not get anywhere else.”

As the battle proceeded, the Americans steadily ate away at Japanese territory, twice forcing them to move their command center deeper into the ridge system in the northern part of the island. Outnumbered and surrounded, the Japanese were also at an extreme disadvantage in terms of the quantity and quality of their equipment. Knecht says that the shoddiness of much of the Japanese materiel left behind on Peleliu made a deep impression on him. “Their helmets were cast iron with really cheap liners underneath and they would just shatter when they got hit by a bullet,” he says. “The American helmets had a big steel pot and a fiberglass liner.” Japanese rifles frequently jammed and were discarded on the battlefield, while American ones were collected for reuse.

On November 24, exactly 10 weeks into the battle, the Japanese army leaders recognized that all hope was gone. In their final command center, in an area termed Death Valley by the Americans, Colonel Nakagawa and Major General Kenjiro Murai died by ritual suicide after burning their regimental colors. The archaeologists visited the site during both of their surveys. “You have to climb down into the cave, and there’s no natural light penetrating there,” says Price. “Every time we went, there were fresh flowers. That takes quite a bit of effort, but somebody remembers.”

Before committing suicide, Nakagawa commanded the 56 surviving able-bodied Japanese soldiers to disperse into small groups and continue to attack the Americans. The Americans declared an official end to the battle on November 27, but sporadic guerilla raids went on for some time. Even after the war was over, some Japanese soldiers held out in a cave near the shore north of the airfield, occasionally harassing the Americans who staffed a garrison on the island.

The 34 men still living in the cave were finally convinced to lay down their arms after being shown letters from Japan confirming that the war was over, and on April 21, 1947, they surrendered. The cave’s entrance was a mere slit, measuring just over three feet high and one foot wide. “Inside, it was just high enough to crouch,” says Knecht. “You’d have to squat at best.” During a ceremony commemorating the 60th anniversary of the battle, Knecht noticed a man in a Japanese marine forage cap sitting on his own. He approached the man, through a translator, and learned that he was Kiyokazu Tsuchida, a veteran of the Imperial Japanese Navy who was part of the group that had held out in the cave. “He told me that they stayed there all day, and at night they’d go to the dumps where the Americans threw their food away,” Knecht recalls. “He said they actually ate better from these dumps than they had during the war.”

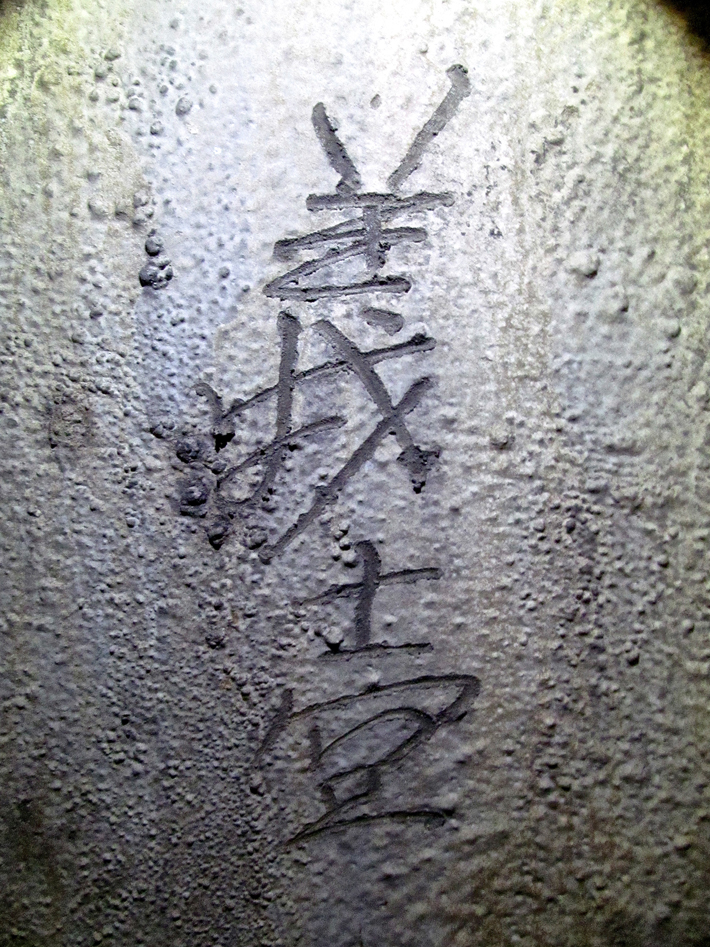

Several hundred of the Korean and Okinawan forced laborers surrendered, but only 19 of the 11,000 Japanese troops who had been on Peleliu at the outset did so, or were captured. The rest fought on despite the dreadful odds they faced, embodying an ethos of extreme nationalist sacrifice inculcated during their training and reinforced even as the battle unfolded. The troops were encouraged to see themselves as gyokusai, or “shattered jewels.” The metaphor had been adopted by nineteenth-century samurai from the seventh-century Chinese Book of Northern Qi, which suggests that “a great man should die as a shattered jewel rather than live as an unbroken tile.”

During the battle, radio broadcasts from Japan regularly reminded the soldiers that the entire nation was counting on them. In addition, Japan’s emperor, Hirohito, personally sent 11 telegrams—more communiqués than he sent during any other World War II conflict—encouraging them to keep up the fight. Colonel Nakagawa explained in his final radio message to the Japanese regional headquarters his decision to commit suicide: “Our sword is broken and we have run out of spears. Sakura. Sakura.” The final words translate to “cherry blossom,” a flower whose short, brilliant existence represents the brief but heroic life of the samurai.

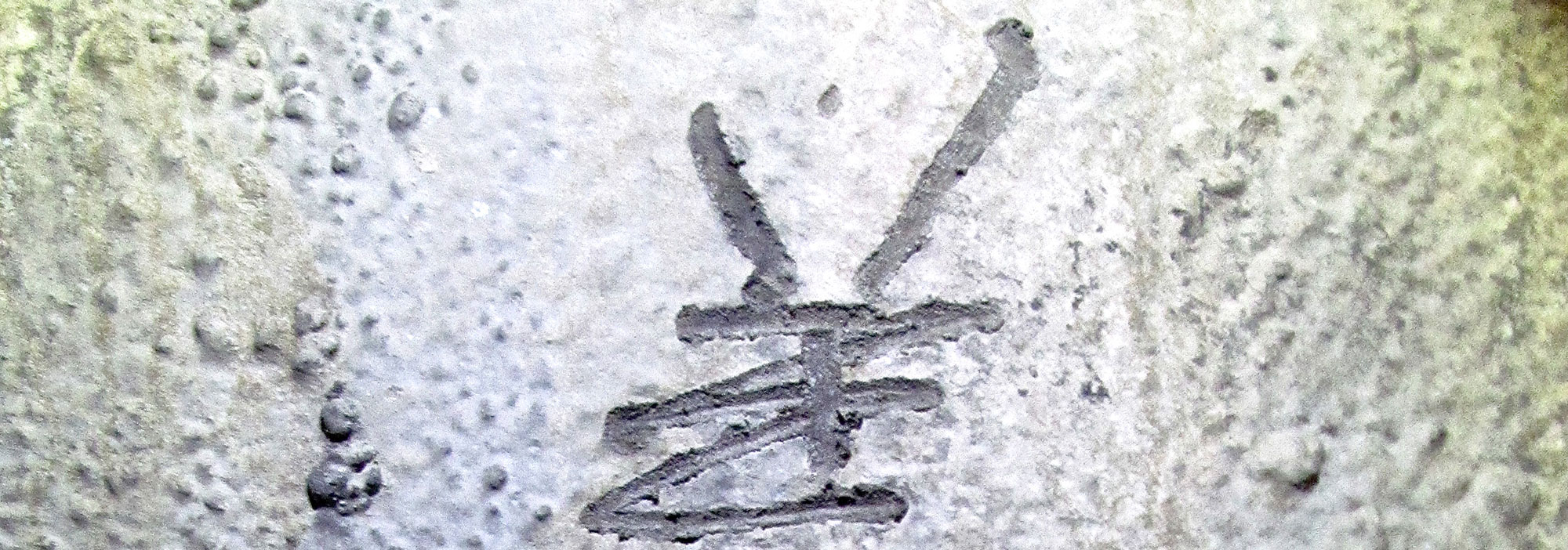

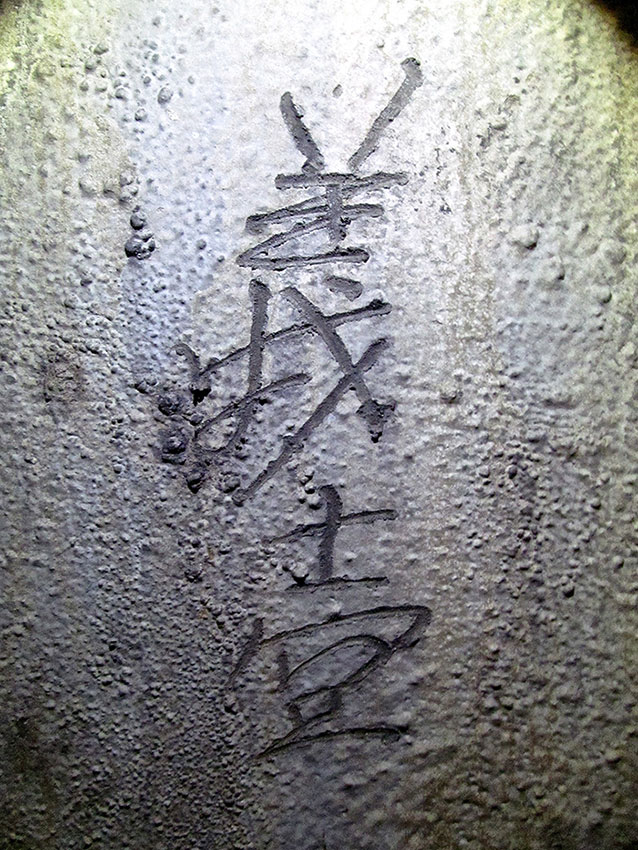

In a large, artificially constructed cave near Peleliu’s airfield, the team uncovered evidence of how deeply this ethos had penetrated into the ranks of the Japanese soldiers who fought on the island. The cave, which was used to store wagons laden with artillery, had been fortified shortly before the invasion, and its walls covered with concrete. The team explored the cave as part of their first survey, and returned during the second to thoroughly document it in photographs. This required setting up a lighting system, likely fully illuminating it for the first time since the battle.

At the back of the cave, they noticed something that had eluded them during their first visit: a Japanese inscription that had been traced with a finger when the concrete was wet. They later learned that it means “Place of the Loyal Samurai.” “The inscription implies that the people who built this cave and garrisoned it during the fight knew exactly what their fate was going to be,” says Raffield. “They were going to stay and defend this place to the death.”