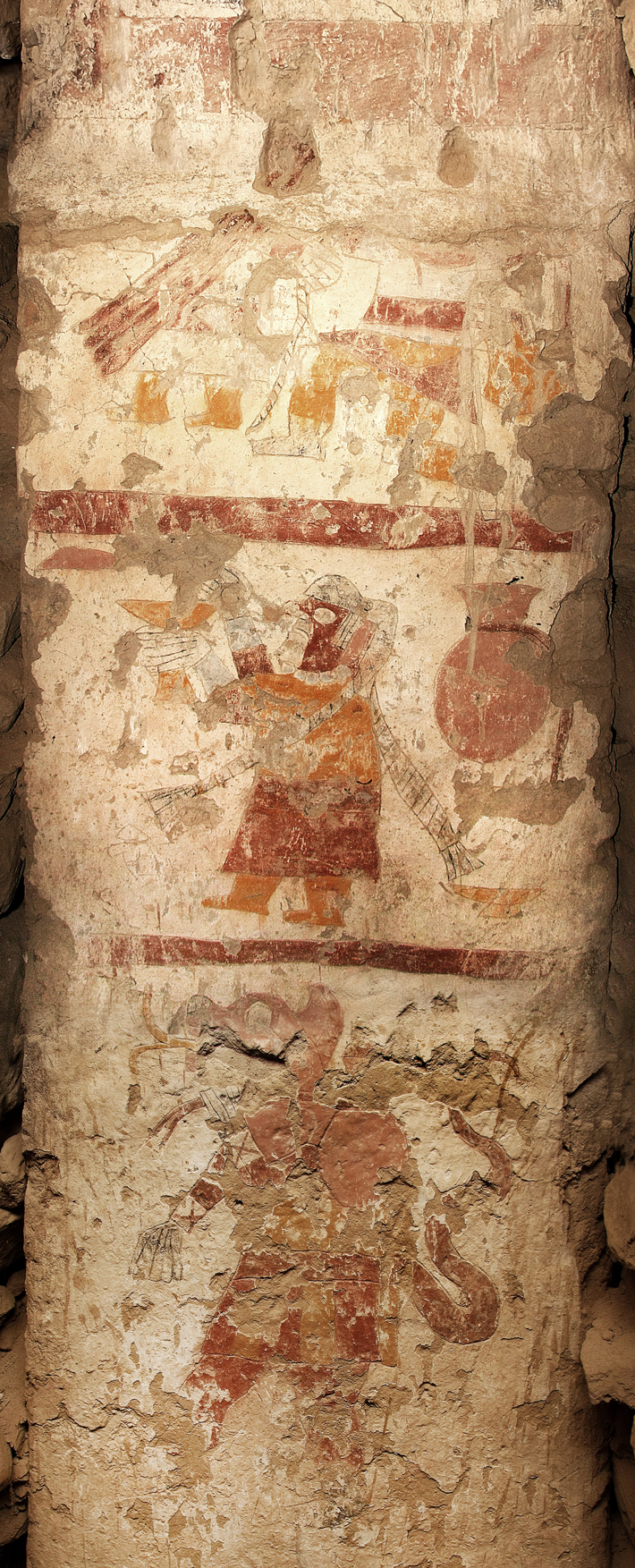

The cover of the Autumn 1951 issue of ARCHAEOLOGY features a dramatic scene of close combat between two men, teeth bared, faces bright red with exertion, garments flying, pulling each other’s hair so violently that each grips the ripped-out forelock of his foe. Created by the artist Pedro Azabache, this cover is a replica of a wall painting at the site of Pañamarca on the northwest coast of Peru, done very shortly after the work’s rediscovery. Mural A depicts a contest between Ai-Apaec, the mythological hero worshipped by the Moche culture, which flourished in this region between about A.D. 200 and 900, and his twin or double. Although Pañamarca’s impressive ruins on a granite outcropping in the lower Nepeña River Valley were well known in the first half of the twentieth century, and had been described by travelers in the late nineteenth century, only a few articles about the site had been published and very little had been said about its wall paintings. Thus, when American archaeologist Richard Schaedel arrived there in 1950, he believed that any paintings he might find would be fragmentary at best. Once there, however, he soon found that Pañamarca’s adobe structures had been completely covered in polychrome murals. In a single week—originally planned for five days, the trip was extended when more murals and a group of burials were discovered—Schaedel and his five-person team not only recorded the combat scene, but also discovered new murals of what he identified as a large cat-demon and an anthropomorphic bird. On the walls of a large plaza, they documented a 30-foot-long composition showing a procession of warriors and priests wearing a costume with knife-shaped backflaps known to have been part of Moche sacrificial rituals.

Though in less than pristine condition after more than 1,000 years, the abundance and unexpected state of preservation of Pañamarca’s murals surprised and delighted Schaedel. But it also concerned him. In his article about the site for Archaeology, he writes, “We hope that this description [of the paintings] will serve as a timely note and warning to lovers of art and archaeology in Peru and elsewhere that this rich source of vivid mural decoration, which today only awaits the patience of the archaeologist to reveal, may tomorrow be irrevocably destroyed. If these still unrevealed documents of the human spirit are not to be forever lost to us, we must constantly keep in mind two ideals: as archaeologists, to devote our attention first and foremost to the adequate documentation of fragile paintings; and to create among the public in general an awareness of their aesthetic as well as their documentary value, so that the present apathy towards their preservation may be replaced by a sense of obligation to their protection.”

Over the more than 65 years since Schaedel’s work at Pañamarca, it was widely assumed that his admonitions had been ignored or forgotten, and that the surviving murals had fallen into ruin. Very little fieldwork was conducted after Schaedel’s excavations and work by Duccio Bonavia later in the 1950s, and only a few new paintings were discovered. When archaeologist and art historian Lisa Trever of the University of California, Berkeley, chose to work in Pañamarca in 2010 along with her Peruvian colleagues Jorge Gamboa, Ricardo Toribio, and Ricardo Morales, she wasn’t very hopeful. “I was pessimistic when we began, figuring that most of the murals that had been discovered before had been destroyed, so we set out to map where the paintings had been and to contextualize what remained,” she says. “But when we began to dig, we were shocked that so much had survived from the earlier excavations.” What was even more surprising was that so much more remained in situ, intact, and unexcavated. “We were soon looking at things that no one had seen since A.D. 780, when parts of the site were deliberately buried,” says Trever. “We went in with a sense that Pañamarca was a site of lost monuments and lost masterpieces of the ancient Peruvian past, and were amazed to find out that not everything was lost at all.”

The name “Moche” or “Mochica” comes not from any ancient source, but was given to the culture in the 1930s because the region’s ancient center was located near the modern town of Moche. Rather than being a single political entity or state, the Moche culture was a loose system of chiefdoms situated in multiple irrigated valleys, linked by shared practices and common beliefs. Their territory encompassed more than 400 miles along the coast of northern Peru. While not exactly a political capital, the cultural and artistic homeland of the Moche world was located in the Chicama and Moche Valleys, near the city of Trujillo. At some point, Pañamarca, which was about 100 miles to the south, grew in religious and cultural importance.

The Moche were skilled builders and artists. At some sites they demonstrated this by undertaking large construction projects. Other locations were peopled with accomplished metalsmiths or expert ceramicists, and still others boasted gifted mural painters. “There is an interesting view developing among scholars about a world of different accomplishments in different places that breaks down the monolithic view of Moche culture,” says Trever. Moche potters created evocative ceramics depicting daily life, the natural world, religious sacrifices, and deformed and even skeletal figures, as well as an extraordinary panoply of hybrid monsters, mythological creatures, and gods in many forms. Gold and silver earspools, necklaces, and rings, some of which are inlaid with semiprecious stones, have been found at many Moche sites. Early Moche artists sculpted clay bas reliefs and covered them with mineral-based pigments at sacred locations such as Huacas de Moche, with its highly decorated Huaca de la Luna, and at Huaca Cao Viejo with its parade of naked captives and intricate geometric patterns. Later, they abandoned the relief style and replaced it with the flat narratives that cover the smooth adobe walls of their temples and public buildings. These paintings reveal much not only about the Moche in general, but also about how Moche rulers chose particular ways of expressing their local identity in a world where heterogeneity reigned.

According to the German linguist Ernst Middendorf, who visited the ruins of Pañamarca in 1886, the Quechua name for the site, “Panamarquilla,” means “little fortress on the right bank of the river.” Trever, however, suggests a different, and more evocative, reading of the name: “little fortress of the paintings.” Pañamarca’s artists were deeply invested in painting, and the murals that cover their monumental temples, including the Temple of the Painted Pillars, reference a Moche ideology focused on either supernatural beings engaging in mythological acts or on human beings performing ritual acts, explains Trever. But adobe is ultimately not permanent—it is eroded and damaged by rain, wind, and time in a way that stone is not. “Because they are building fast, they are constantly remaking their built environment. This gives an immediate sense of their ongoing engagement with the living world,” says Trever. “And because Moche architecture, like Mesoamerican architecture, is renovated and not knocked down, what you end up with is like a set of architectural nesting dolls or onion skins.”

Furthermore, at Pañamarca, Trever sees a localized expression of identity reflected in the murals that is very different from what can be seen at other Moche sites. She believes there was an anxiety about being in the hinterland, 100 miles from the Moche epicenter, that may have led to an increased sense of orthodoxy in the imagery. “What is striking here is that we don’t see a hybrid form of Moche at all, but an even more conservative, even more explicit, Moche ideology expressed,” she says. “It’s almost like they have doubled down on the canon because they are in a more remote location intermingling with peoples of other cultures who aren’t like them.”

What is also unusual at Pañamarca is that there is a density of these canonical images not only in the most public, visible spaces of the temples, but also in restricted, private spaces. While at Huaca de la Luna the inside of many of the temple’s rooms are simply white, at Pañamarca every surface that Trever and her team have excavated is covered in paintings. “It’s almost as if they needed to remind even themselves at every step what it means to be part of a culture, especially when you are far from the heartland,” explains Trever. Says Peruvian archaeologist Gabriel Prieto, “Whatever the reason was to paint all these murals here, it’s clear to me that one of the intentions was to show users of and visitors to these monuments the complexity, quality, and order of the Moche’s most important rituals, stories, and, perhaps, historic events. The paintings at Pañamarca are 100 percent Moche, but the style clearly shows some local taste, and this can tell us that the Moche were adaptable and flexible enough to forge relationships with local elites of other cultures.”

Though much about Moche art and architecture is well understood, key questions about significant changes in painting styles over time—and how these might be related to shifts in Moche fortunes—are at the forefront of current work. Roughly four centuries after the culture first appeared, some sort of disruption rippled throughout the entire Moche world. The cause, according to archaeologist Michele Koons of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, is the million-dollar question. One possible explanation is an El Niño event, but Koons says that researchers have not yet found definitive evidence of this. She says, “I think that it was probably a mixture of different things—possibly climate change or drought, an earthquake, or some other natural disaster, as well as pressure from highland powers such as the Wari.”

It is not only the cause of the episode, but also the precise date that Koons is interested in. “I realized during the course of my research [at the previously unexcavated Moche site of Licapa II in the Chicama Valley] that the traditional dating for the Moche wasn’t really based on any data, but was built on assumptions about pottery styles that had no relationship to actual dates of any kind,” she explains. “I felt the need to unpack this.” By radiocarbon dating organic remains such as seeds and twigs found in excavated contexts alongside Moche ceramics at multiple sites, Koons was able for the first time to pinpoint the date of the catastrophic event or series of events at around A.D. 600.

With this newly refined chronology in mind, archaeologists are now able to recognize a fundamental shift in the way Moche leaders presented themselves to their communities and the outside world. “There is some sense at this time that people aren’t really buying into the current way of doing things,” says Koons, “and that their claim to leadership needs to be bolstered. This could have happened for any number of reasons.” For example, climatic events may have caused people to lose faith in their leaders’ ability to protect them. At Moche sites such as Huaca de la Luna, this change in perception is reflected in the murals, which become less repetitive and more narrative. Koons believes that this type of art reveals an awareness of not just who they are, but who they have been. For example, the iconography of sacrifice, which was depicted in Moche art for centuries, can be seen in a nearly documentary manner. “There is a sense that they are saying, ‘This is what we used to do,’” explains Koons. “It’s as if they are becoming more self-reflective and more aware of themselves at some transitional moment.”

The tremendous challenge faced by Trever and her team is that, while the history of other Moche sites prior to A.D. 600 is relatively well understood, the story of Pañamarca earlier than that date is somewhat dark—nothing has been excavated and little is known. What does seem clear is that Pañamarca’s inhabitants ultimately recovered from whatever happened at the start of the seventh century, and that they experienced a kind of renaissance that would last for some 150 years. “The story of Pañamarca is not just about crisis, but also about recovery,” says Trever. It was during this latter phase, on the site of an earlier temple, that Pañamarca’s rulers supervised the construction and expansion of the large walled plaza and monumental adobe pyramids and platforms they covered with vibrant murals. And, as a result of radiocarbon dating of organic construction materials, it is now possible to say that these structures were built between A.D. 600 and 750, the first absolute dates for the Moche in this valley. Still, questions remain unanswered. “Pañamarca’s paintings seem to me to be a large open book, and when I saw them I felt like the Moche were trying to tell me something about their civilization and their glorious past,” says Prieto. What exactly they were saying is still something of a mystery.

Slideshow: Exploring Moche Murals

Located on Peru’s northwest coast, Pañamarca was one of many ceremonial centers sacred to the Moche people. Below are detailed explanations of the iconography of some of the best preserved murals that adorn the adobe structures at the site.