Twenty miles southwest of Rome, obscured by agricultural fields, woodlands, and the modern infrastructure of one of Europe’s busiest airports, lies what may be ancient Rome’s greatest engineering achievement, and arguably its most important: Portus. Although almost entirely silted in today, at its height, Portus was Rome’s principal maritime harbor, catering to thousands of ships annually. It served as the primary hub for the import, warehousing, and distribution of resources, most importantly grain, that ensured the stability of both Rome and the empire. “For Rome to have worked at capacity, Portus needed to work at capacity,” says archaeologist Simon Keay. “The fortunes of the city are inextricably tied to it. It’s quite hard to overestimate.” Portus was the answer to Rome’s centuries-long search for an efficient deepwater harbor. In the end, as only the Romans could do, they simply dug one.

Although it had previously received little attention archaeologically, over the last decade and half Portus has been the focus of an ambitious project that is rediscovering the grandeur of the port, its relationship to Rome, and the unparalleled role it played as the centerpiece of Rome’s Mediterranean port system. Keay, of the University of Southampton, is currently director of the Portus Project, now in its fifth year, but has been leading fieldwork in and around the site since the late 1990s. He is part of a multinational team investigating Portus’ beginnings in the first century A.D., its evolution into the main port of Rome, and, ultimately, the complex dynamics of the port’s relationship with the city and the broader Roman Mediterranean. The multifaceted project involves a number of institutions, including the United Kingdom’s Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British School at Rome, the University of Cambridge, and the Archaeological Superintendency of Rome.

One of the difficulties the team has faced in addition to the site’s enormous size is its complexity. Portus encompasses not only two man-made harbor basins, but all of the infrastructure associated with a small city, including temples, administrative buildings, warehouses, canals, and roads. Archaeologists have taken many approaches to investigating Portus. “Methodologically, the strategy has been to combine large-scale, extensive work using every kind of geophysical and topographic technique, with excavation reserved for relatively focused areas,” says Keay. “The aim is to try and understand a key area at the center of the port, which could provide a point from which to understand how the port worked as a whole.” The current archaeological research is offering a new understanding of just how Portus’ construction enabled Rome to become Rome.

By the dawn of the first century A.D., just before Portus was conceived, Roman territory stretched from Iberia to the Near East, enveloping all the coastal land bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Romans considered the Mediterranean such an innate part of Roman life that they often referred to it simply as Mare Nostrum, or “our sea.” However, paradoxically, as it was located nearly 20 miles inland, Rome was without a suitable nearby maritime port. This obstacle had periodically inconvenienced the city over the course of the previous millennium. In a sense, Rome’s growth had always relied on its capacity to connect with ever-broadening Italian and Mediterranean trade networks. The more Rome expanded, the more it turned to outside resources to feed its population.

Throughout its history, Rome’s size and potential always seemed to be commensurate with—and limited by—its port capabilities. During the first half of the first millennium B.C., the early Roman settlement relied on a small river harbor at the foot of the Capitoline, Palatine, and Aventine Hills, where a near-90-degree bend in the Tiber River created a small plain and natural landing for boats. Known as the Forum Boarium and the Portus Tiberinus, the site was also where two important ancient Italic trade routes crossed. This river port was, at this early juncture in Rome’s history, the heart of its supply, communication, and redistribution activities. Archaeological evidence found there, among the earliest ever discovered in Rome, indicates that even during the city’s early days, Romans were interacting with foreign travelers and importing goods from across the Mediterranean. By the fourth century B.C., as Rome was expanding beyond the site of the original seven hills and into central Italy, it began to outgrow its limited river port. Although Rome was connected to the sea via the Tiber River, seagoing ships and boats of substantial size could not safely maneuver up the river’s course to the city.

A significant step was taken in 386 B.C. when Rome founded the colony of Ostia at the Tiber’s mouth, some 20 miles away, not only to help supply the growing city with grain and other foodstuffs, but to enhance its connections with the Mediterranean. While Ostia eventually became a significant Roman city and played a major role in imperial Rome’s multifaceted port system, it proved insufficient as the city’s sole port. Although adjacent to the Mediterranean Sea, the site had geographical drawbacks. “Ostia could never handle massive numbers of ships,” says Keay. “It’s a river port, and the river itself is no good. It floods, it’s treacherous at the river mouth, and it’s not really deep enough.”

Still limited by its lack of a deepwater maritime port, the Romans began to look southward. By the second century B.C., Rome controlled most of the Italian peninsula, as well as parts of Iberia, Greece, and North Africa. Roman ships were now bigger and were sailing farther abroad more frequently. The river port of Rome, Portus Tiberinus, even when combined with Ostia, couldn’t meet the increasing demands of an expanding Mediterranean-wide trade network. The establishment of Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) on the Bay of Naples formed part of the solution. At Puteoli, the Romans finally had a natural maritime harbor that could accommodate ships of all sizes as well as increased traffic. Puteoli evolved into the principal port of the Roman Republic, and remained so for two hundred years. But Puteoli itself was not without its limitations: Rome’s greatest commercial harbor was located more than a hundred miles south of the capital. Goods arriving on large ships had to be offloaded at the Bay of Naples and carted up to Rome overland, or transshipped onto smaller boats and ferried up the coast to Ostia, a three-day sail away. “It’s not ideal,” says Keay, adding, “The Romans realized this and toyed with the idea of building a port closer to Rome, an anchorage that would speed up the whole process and make it more efficient.”

By the beginning of the empire at the end of the first century B.C., the population of Rome and its environs had reached well over a million people. The lack of a nearby maritime port was beginning to make supplying the city a nearly impossible task. With its territory now spread from one end of the Mediterranean to the other, resources from every region sailed to Rome. Olive oil, wine, garum (a popular fish sauce), slaves, and building materials were shipped from places such as Spain, Gaul, North Africa, and the Near East. However, the most important responsibility of the Roman emperor was ensuring the steady and continuous flow of grain. Grains and cereals were the staple of the Roman diet, either consumed in bread form or served as a porridge. It has been estimated that a Roman adult consumed 400 to 600 pounds of wheat per year. With a population of more than a million, this required Rome to stock a staggering 650 million pounds annually. Throughout Rome’s history, shortages in the grain supply led to riots. The city’s food supply was frequently interrupted by storms and bad weather, and grain ships could be lost at sea. Any such delay or loss created civil unrest.

From the second century B.C. onward, the Roman government took an increasingly active approach to monitoring and controlling the grain supply. First, the government began to regulate and subsidize the price, ensuring that grain remained affordable to the masses at all times. By the Augustan period, the emperor was doling out as much as 500 pounds of grain per head to as many as 250,000 households. The emperors realized that the key to Rome’s stability was keeping its population well fed.

Yet, by the first century A.D., Rome could no longer be sustained by Italian harvests alone. It began to exploit its newly annexed fertile provinces, especially North Africa and Egypt, which soon became the largest supplier of Roman grain. It took as many as a thousand ships, constantly sailing, just to support the demand for grain in the city. With large grain ships typically capable of hauling more than 100 tons, and sea transport at least 40 times less expensive than land transport, Rome desperately needed a deepwater port close to home.

At about this same time, Roman engineering was beginning to manifest its unparalleled capabilities. The emperor Claudius concluded that the time was right to build an artificial port within Rome’s environs, one large enough to accommodate the demands of an ever-growing city. Portus was built from scratch, a couple of miles north of Ostia, along a coastal strip on the Mediterranean near the mouth of the Tiber River. It would become the linchpin in a new imperial port system that enabled Rome to be continuously and efficiently supplied for the next 400 years.

The enormous engineering project was begun by Claudius around A.D. 46 and took nearly 20 years to complete. It was the largest public works project of its era. At its center was an artificial basin of nearly 500 acres, dug out of coastal dunes. A short distance from the mouth of this harbor were two extensive moles, or breakwaters, constructed to protect it from the open sea. A small island with a lighthouse stood between the two moles and guided ships as they approached. With a depth of 20 feet, the Claudian basin was large enough, deep enough, and sheltered enough to provide ample anchorage for large seafaring ships heavily laden with as much as 500 tons of cargo.

In addition to the large basin, this early stage in Portus’ construction involved other facilities such as a smaller inner harbor known as the darsena, and various buildings associated with the registration, storage, and distribution of goods. The harbor complex was connected to the Tiber River two miles to the south via a network of canals, the largest of which measured nearly 100 yards wide. This greatly expedited the whole process of bringing goods from cargo ships to Roman households. Enormous warehouses were built at Portus that were capable of storing many months’ worth of grain. Portus became not only the place through which foodstuffs entered Rome, but also where they were stored.

The construction of Portus brought great renown to Claudius and, later, to his successor Nero, who saw it to completion. Portus was commemorated on coins issued by the emperors and on a monumental arch erected by Claudius at the site. “There is an element to the port of Claudius that makes it clear that it is a vanity project,” says Keay, “and there is also an element that reflects the rhetoric of empire. The emperor is the great provider, who overrides nature in order to feed his people.”

The establishment of Portus by Claudius was just the first step in a process that led to the continual expansion and enhancement of the site over the next two centuries. In the early second century A.D., as Rome grew to its greatest territorial extent, the emperor Trajan was responsible for a massive enlargement and reorganization of Portus. Trajan, whose building projects were transforming the city of Rome, turned his architects toward the redevelopment of the existing harbor. As with many Trajanic projects, the goal was not only to provide new functional facilities, but ones that also symbolically celebrated the power and glory of his empire.

At the heart of Trajan’s new harbor was another artificially dug basin just east of the existing Claudian basin. Its hexagonal shape, which has become Portus’ most iconic feature, survives today as a private lake for fishing on the estate of Duke Sforza Cesarini. The unusual design, which had no precedents in Roman harbor construction, provided increased functionality, as well as a unique aesthetic signature. The hexagonal basin not only increased Portus’ overall protected harbor space by nearly 600 acres, but the six sides of the new basin expedited the docking and unloading processes. Each of its sides, at a length of almost 1,200 feet, provided ample quayside space for berthing ships and handling cargo.

The process could not have been more streamlined. The new Trajanic harbor could accommodate about 200 ships, in addition to the 300 anchored in the Claudian basin. Rome had at last created a port suitable to its far-reaching Mediterranean maritime empire. If Claudius’ Portus was a statement of Rome’s ability to alter natural topography, Trajan’s harbor was a celebration of Rome’s design and construction capabilities. Each side of the hexagonal basin was adorned with new monumental buildings designed so that any traveler sailing into the harbor would be immediately confronted with the grandeur and power of Rome. Sightlines from the harbor led straight to impressive porticoes, temples, warehouses, and even a statue of Trajan, all framing the waterfront. In addition to its functionality, Portus was designed to deliver the message that Rome reigned supreme. “Portus is a statement about imperial power—it controls not just the Mediterranean but nature itself. It’s really the only time that the Mediterranean has been controlled by a single political power, and this port played a key role in enabling its authority to be maintained; only the Ottomans come close,” explains Keay.

Over the last few years, the Portus Project has been working on what would have been a thin isthmus of land between the Claudian and Trajanic harbors. There the team has uncovered the foundations of what Keay refers to as a shipyard—a massive warehouse-type structure associated with the dry-docking and maintenance of ships. The 780-by-200-foot building is believed to have stood nearly 60 feet high. Its facade was divided into a series of arched bays, some 40 feet wide, that opened onto the hexagonal basin. Keay thinks that the structure could also have some association with Roman naval activity. “Portus is the place from which the emperor sails out, and it’s the place from which new governors go out to their provinces,” he says. “There was a security issue at Portus, and it makes sense that there was a naval detachment here. I think our big building is part of that in some way.”

There is also some evidence that the emperor himself maintained a presence at the site. Near the shipyard, the Portus Project has also investigated the so-called Palazzo Imperiale (Imperial Palace). This multifunctional complex covered nearly seven and a half acres, with prominent views across both basins. The three-story structure contained all of the appurtenances of a wealthy Roman villa—porticoes, mosaics, peristyles, and ornamental dining rooms, but also contained storerooms, offices, and production areas. Recently it was discovered that a small amphitheater was even added to the complex later in the third century. While the lack of epigraphic evidence makes it impossible to associate the building directly with the emperor, Keay believes it certainly would have been used by high-ranking government officials and representatives of the emperor who oversaw all aspects of port activity.

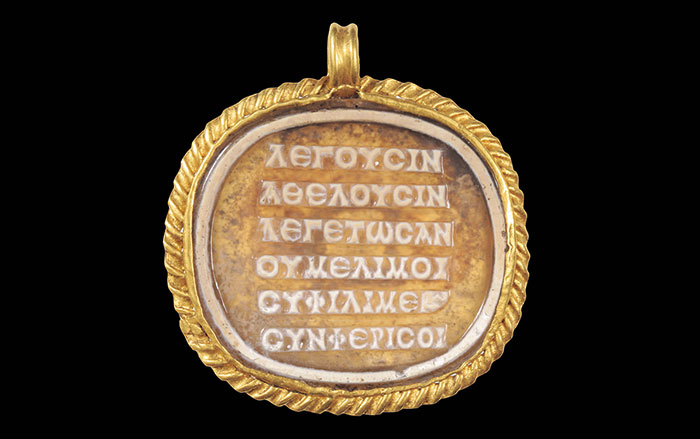

At its height, Portus may have catered to a seasonal population of 10,000 to 15,000 people, although it was not primarily a residential site. Its bustling crowds would have consisted of merchants, shippers, dockworkers, administrators, and government agents, many of whom commuted from larger cities such as Ostia or even Rome. The traffic to and from the harbor is estimated to have been several thousand seagoing ships annually, as well as hundreds of smaller boats and barges that maneuvered around the various basins and canals and up the Tiber River. Once a ship entered Portus, it might temporarily anchor in either the inner or outer harbor basin as it awaited a berth quayside or for smaller boats to transship its cargo. After freight was registered and recorded, it was loaded into warehouses or onto smaller barges to be brought along the various canals and towed up the Tiber to Rome. Insight into the organization of the importation process and the procedures Roman officials followed has been uncovered at Monte Testaccio in Rome, where transport amphoras were discarded. Some of the amphoras bear small tituli picti—painted notations that record information about the type of product, its weight, origin, destination, merchant, or shipper. The tituli picti demonstrate how thoroughly each product was examined and the painstaking measures employed for each shipment of goods. “I think there’s an unimaginable complexity to the registration of cargo. The person responsible for the port needs to know where to assign ships, where particular cargoes belonging to particular merchants go, how material gets from one storeroom to another and then onto the boats that go up the Tiber,” says Keay. “It’s highly complex.”

Ports all over the Mediterranean, including Carthage, Ephesus, Leptis Magna, and Massalia, as well as those in Italy such as Puteoli, Ostia, and Centumcellae, formed the extensive network that allowed the Romans to bring the resources of foreign lands to Rome. Many of the goods brought to Portus were destined for the capital, while others were immediately redistributed to other ports in the Mediterranean. Portus, as the primary port of Rome itself, was the cornerstone of that system.

Writing in the second century A.D., the famed Greek orator Aelius Aristides marveled at the scope and efficiency of Rome’s maritime capabilities. “Here is brought from every land and sea, all the crops of the seasons and the produce of each land. The arrivals and departures of the ships never stop, so that one would express admiration not only for the harbor, but even for the sea. Everything comes here, all that is produced and grown … whatever one does not see here, it is not a thing which has existed or exists.” As the centerpiece of Rome’s grand shipping network, Portus allowed the city to enjoy all the resources of the known world—and left foreigners such as Aristides in wonder and amazement.