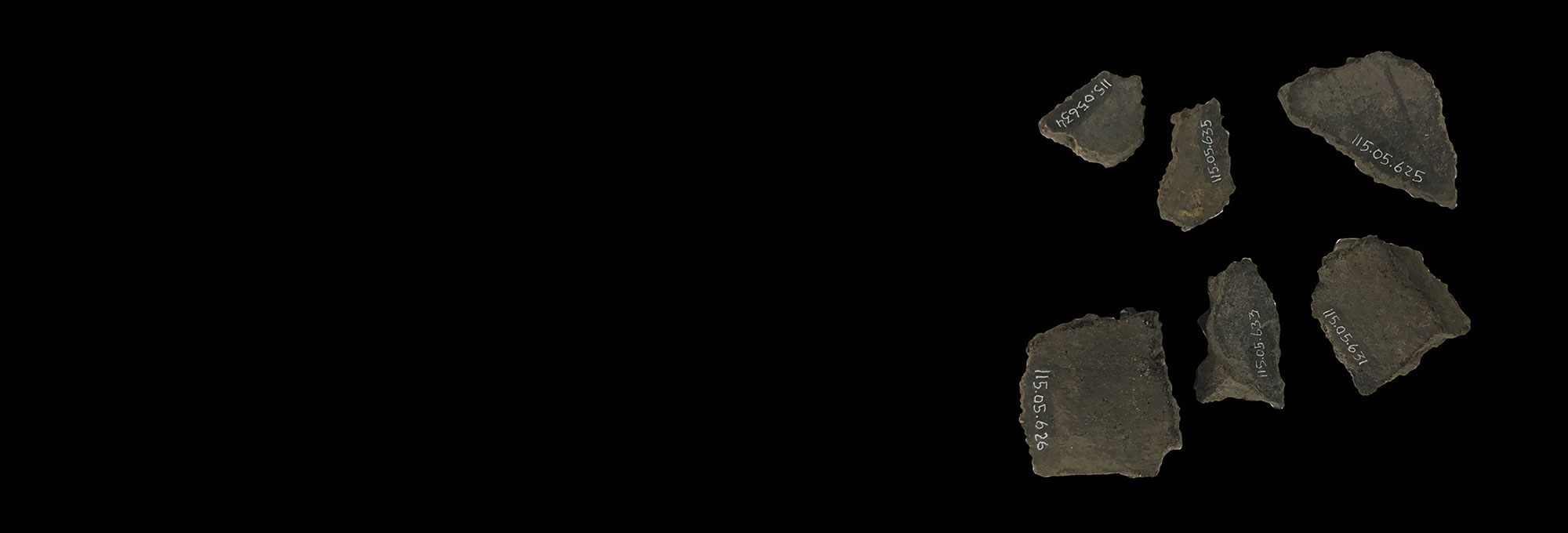

Indigenous people began building earthen mounds more than 4,000 years ago in the Patos Lagoon estuary on the coast of southern Brazil. Researchers have now found evidence that these mounds served as gathering places for feasts connected to the seasonal abundance of fish. Working as part of the TRADITION project, a team including archaeological scientist Marjolein Admiraal, then of the University of York, employed molecular and isotope analysis to examine food residues on potsherds recovered from two mounds at the site of Pontal da Barra, on the lagoon’s southern end. These mounds were constructed between about 2,300 and 1,200 years ago. Researchers were surprised to discover that the sherds showed that people had used the vessels for two very different purposes.

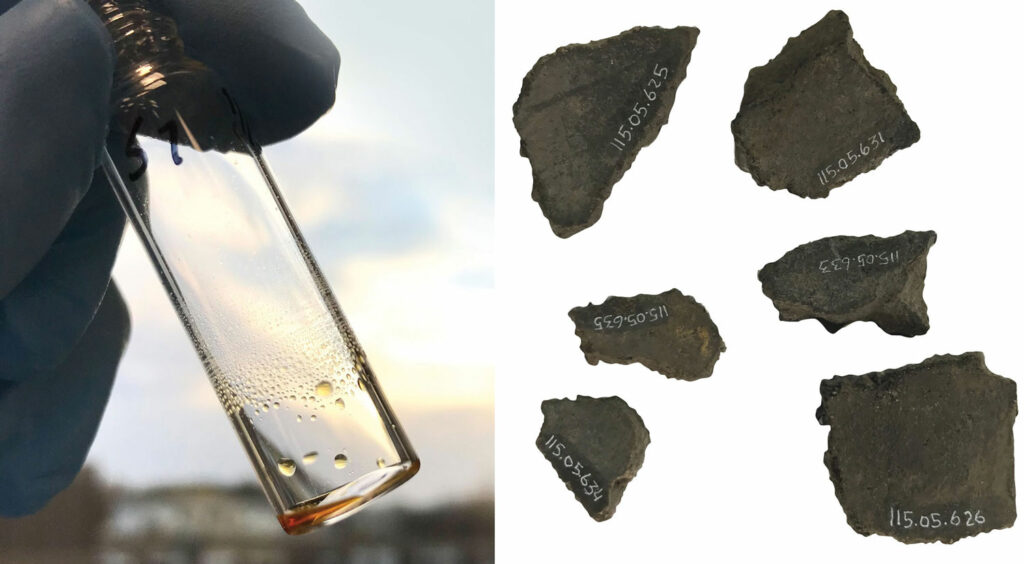

On certain sherds, the team detected high concentrations of fatty acids associated with marine species. This indicates that Indigenous people used the vessels to cook fish such as whitemouth croaker and catfish, remains of which have been found at the site. Other sherds had very low amounts of lipids, but included biomarkers for plants such as maize and palm. On these pots, the team also identified signs of heating and lipids called bacteriohopanes—markers of bacterial action likely produced by fermentation. Admiraal explains that other Brazilian Indigenous groups sometimes heated plants to produce fermented drinks. “We suggest that the mound builders may also have fermented plants to make alcoholic beverages,” Admiraal says, “and that this was connected to seasonal celebrations that attracted people from the wider region.”