Peru's towering burial mounds, with their underground chambers and layers upon layers of history, had long been thought to be a distinctive feature of the country's arid coast.

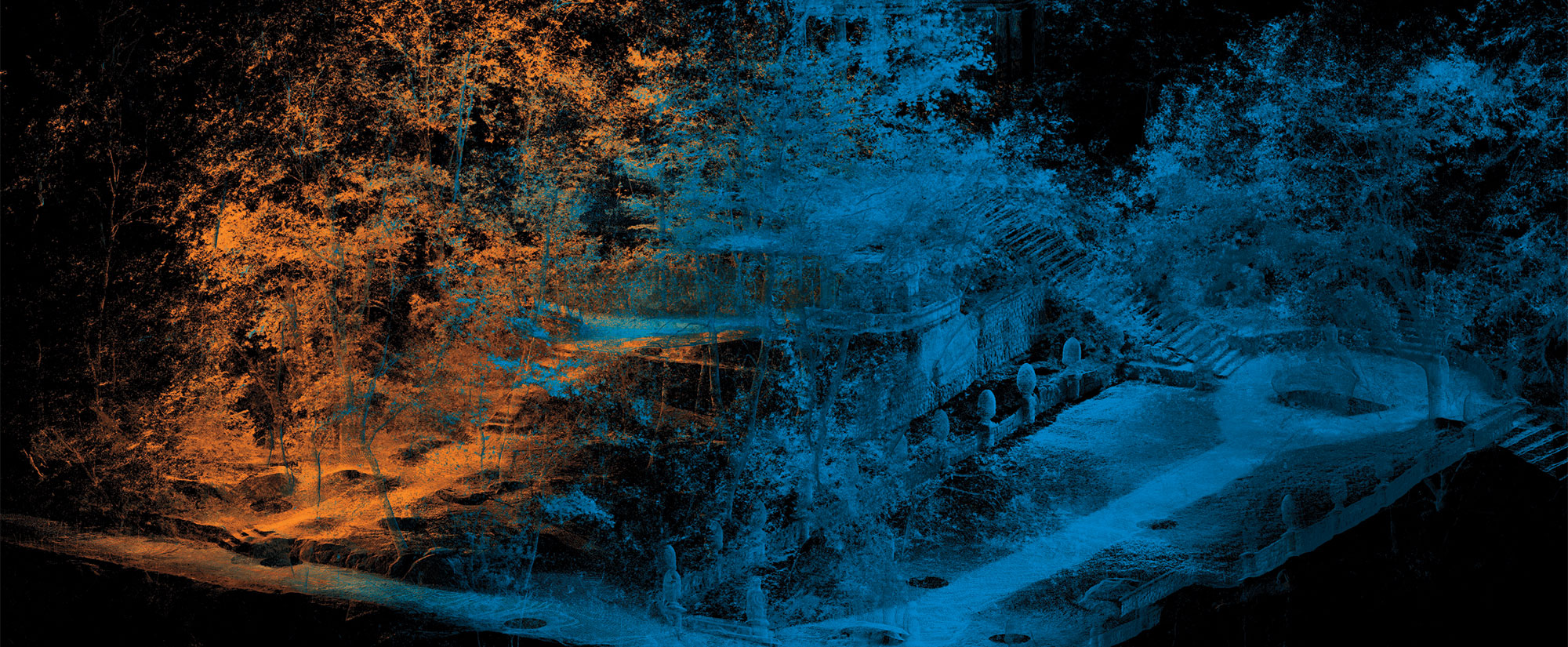

But the discovery of two ancient pyramid complexes near the town of Jaen, on the western edge of the Amazon lowlands, shows that monumental architecture had spread across the Andes and well into the jungle thousands of years before the Spaniards arrived. The largest mound, over an acre at its base, was overgrown with vegetation and used by modern townspeople as a dump and latrine before Peruvian archaeologist Quirino Olivera, of the Friends of the Museum of Sipán, began excavating there. He soon found evidence of construction on a massive scale--walls up to three feet thick, ramps, and signs of successive building phases stretching back at least 2,800 years.

"People had assumed monumental architecture never reached the jungle. This discovery shows it did," says Olivera. "To build these structures, people must have had knowledge of engineering and design, and a large, stable work force. Until now, it was assumed they lived in huts made of tree trunks and leaves."

At the same pyramid he found the tomb of a high-status man who, at his burial around 800 B.C., was decked out with the shells of some 180 land snails. A layer of snails covered the man's torso, and more shells adorned his head and limbs. The man was probably a healer or priest of some kind, says Olivera. He found marine mollusk shells in another tomb nearby, testament to the busy trade ties from the coast over the Andes to the jungle. The finds suggest that, along with sophisticated architecture, complex worship had spread far from the coast centuries before once believed.