I thread my legs into snake guards—canvas chaps with hard plastic shin covers that hook to my jeans. Standing beside a rented van, I see the same scenery all around—thick woods scalloped by broom straw and river cane. I silently lace muck boots, don an expedition hat, heft a backpack, and join a small group of students preparing to hike into the heart of the Great Dismal Swamp. I ask the person standing next to me if the snake guards stay on all day. I get a look that I interpret as, "Are you kidding?" I've doused myself with bug spray, pushed my socks into my boots, and stowed a half-liter of water in my bag, along with crackers and raisins I later realize won't get me through the day's hike.

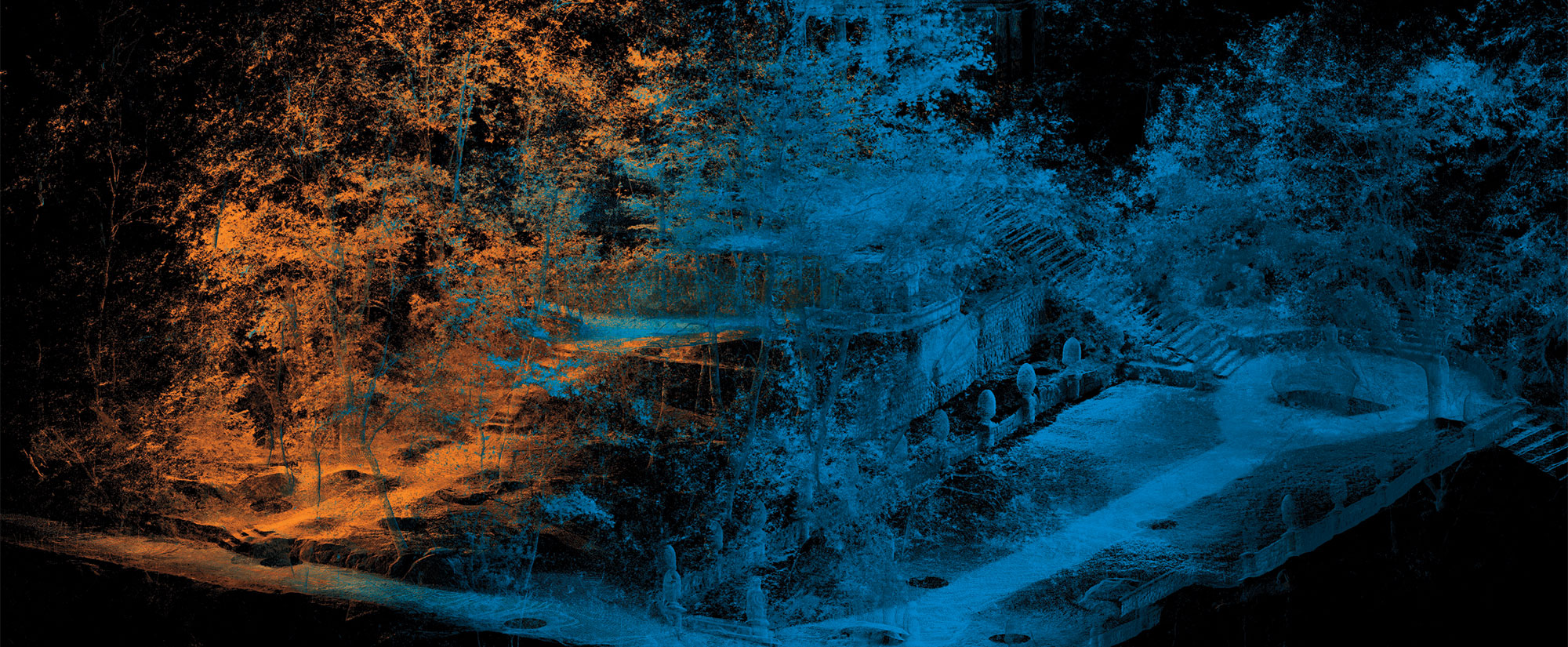

The Great Dismal Swamp spans about 200 square miles of North Carolina and Virginia, down from 2,000, due in part to an aggressive canal project that divided and drained it by 1805. Despite that development and all that has come since, it lives up to its name—unsettling, isolated, and uncivilized. As we head out, American University graduate student Cynthia Goode invites me to stick close. "I know where the deep holes are," she says.

The place is so inhospitable that when it was surveyed in 1728, Col. William Byrd II, a commissioner charged with setting a boundary between North Carolina and Virginia, wrote, "We found the ground moist and trembling under our feet like a quagmire, insomuch that it was an easy matter to run a ten foot pole up to the head in it, without exerting any uncommon strength to do it." He added, "Never was rum, that cordial of life, found more necessary than it was in this dirty place."

We set off from a clearing within the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, about 45 minutes from its main entrance in Suffolk, Virginia. We are going to an interior site so remote that it's impossible to find without an experienced guide like American University anthropologist Daniel Sayers. He's spent most of the past eight years in this place, searching one shovelful of dirt at a time for the rare traces of escaped slaves who made homes in this unforgiving place. For these fugitive slaves, known as maroons, facing the Dismal's heat, quicksand, bugs, snakes, and bears was a reasonable price for a chance at freedom and self-determination.

Maroons appear wherever slavery has existed—such as in the Caribbean and South America. The provenance of the term "maroon" is unclear. Some trace it to the Spanish word cimarrón, which means "wild" or "runaway slave," but recent scholarship shows it may have derived from a Spanish translation of an ancient Arawak or Taino word meaning "fierce" and "wild." In the American South, maroons often hid in swamps to evade the trained dogs, armed bands of angry whites, and even soldiers who pursued them. The isolation of these communities—the obscurity on which they depended—often means they have been overlooked by historians.

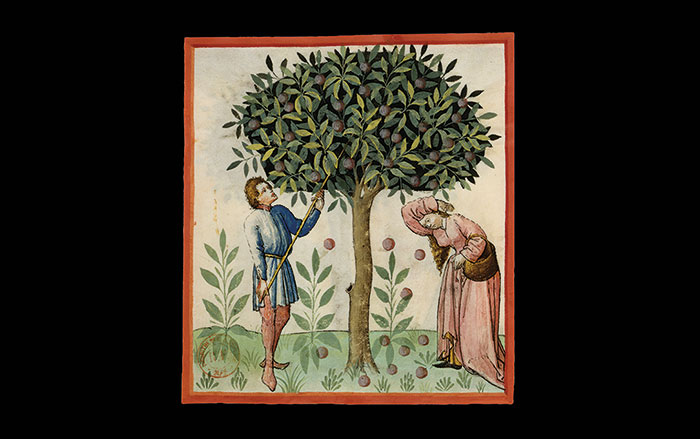

The Great Dismal Swamp was long such a sanctuary. Native Americans found refuge here after Europeans arrived. Soon after, maroons made their way to the same high and dry areas, known as mesic islands, that are found far from the swamp's marshy edges. The islands' unmatched natural defense—surrounded by several boggy miles—allowed complex refugee communities to arise here, with sustainable agriculture, commerce, and cultural arts, Sayers says. The escaped slaves threw off captivity and created a self-reliant subsistence society using available materials. Starting with the expansion of slavery after 1660 and continuing until the mid-1800s, the swamp was a parallel world for escapees, where maroons could live freely in a state Sayers calls "self-emancipation"—a difficult life, but a free one.

"There were hardships," says Sayers. "But working in the brutal cotton fields with overseers, not to mention life after the day's labors—compared to this? You may have to work for five hours to grow food, but there was really a self-reliant ethos."

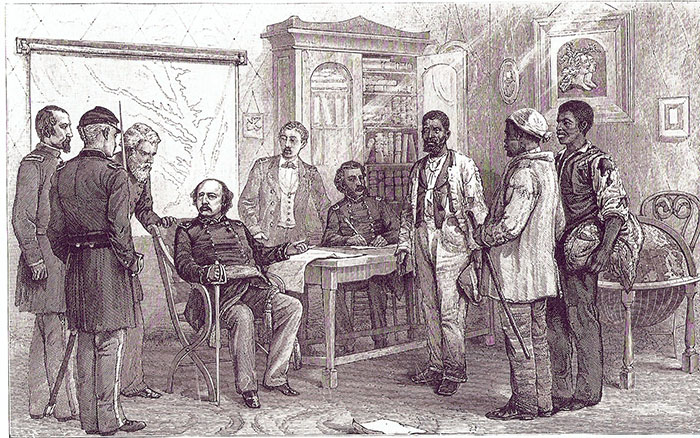

While accounts from the time agree that the swamp hid hundreds or even thousands of escaped slaves, they lack clear information about their daily life and social structures. Here's where the Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study, as the overall project is known, will help.

A narrow footbridge, across a nineteenth-century canal, tinkles with the gentle sound of bells to scare off bears. We cross the bridge, following a route that lies underwater for much of the year. Soon we are up to our knees in muck. We encounter insects, thorny vines, brush, and brambles so thick that even after weeks of use this field season, the path still needs to be cleared by machete. After about 2,000 feet, the trail dries and the land gradually rises. We are close to one of the raised, interior islands, with up to 20 acres of clearings

and wooded areas.

Sayers, a tall man with long hair and a rugged, handsome face, has explored the Dismal since 2003, alone or with small teams of students and archaeologists, searching for traces left by the maroons. These days, he's fully at home here, describing landmarks and distances as if talking about his backyard. He's unfazed by the heat and heavy gear, and walks among the excavation squares with a measured, unhurried pace. Because he is the first to excavate in the modern swamp, it has taken time to find sites, soil features, and artifacts. Last year he received a $200,000 "We the People" award from the National Endowment for the Humanities that has allowed him to dig deeper, enlarge his area of study, and conduct soil tests.

Some distance through the woods, we arrive at one of Sayers' earliest study areas, a one-and-a-half acre area he calls the "grotto." Except for the bugs, it's easy to forget I'm in a swamp. The ground is crunchy with dead leaves and free of brush tangles. A deer passes, then bounds away. With a sweep of his arm Sayers points out where, in 2004, he found a semicircle of 83 round postholes. About three inches below the surface, they likely represented a structure erected by Native Americans in the very early historical period (ca. 1600–1650). He also found lead shot, knife-cut bone, and several stone artifacts. "I thought ‘Okay, we know this is here, let's expand on it,'" he says. "You have all this documentation pointing to the fact that potentially thousands of people went in there prior to 1800, even some outcast or criminalized Europeans."

On the other side of the clearing he indicates the location of a fire pit and at least one cabin, the latter probably dating to the second half of the seventeenth century. It was probably built by refugee slaves, but the grotto, like most of the swamp, was home to a succession of communities over the centuries. Here, Sayers found the partial footprint of another cabin that appears to have been set using round posts. A square posthole, which would have been made after European contact, also appears on the site. Between the posts he found evidence of fill, likely from logs placed between them. During more than a year of extensive work at the grotto, he found evidence of 150 features representing at least five cabins, including one L-shaped section of a structure—a doorway and outer wall. These indicate a thriving maroon community, he believes. Because the site is so remote, it remained largely undisturbed except for wildlife activity. The architectural features, when exposed, appear as dark shapes against the orange clay soil layer beneath a loose covering of leaves, organic debris, and peat. A technique called optically stimulated luminescence dating, which determines when sand was last exposed to natural light, dates the site to sometime between 1600 and 1759.

"We know no one else was out here—there's no other explanation for who's building cabins except what the documents are indicating, which is that a lot of people fled here," Sayers says. Indeed, Byrd's 1728 survey team came across an African-American family who claimed to be free (which Byrd doubted). Another writer, J.F.D. Smyth, wrote, "Run-away negroes have resided in these places for twelve, twenty, or thirty years and upwards, subsisting themselves in the swamp upon corn, hogs, and fowls that they raised on some of the spots not perpetually under water, nor subject to be flooded, as forty-nine parts out of fifty are; and on such spots they have erected habitations, and cleared small fields around them."

We walk along a gentle rise in the clearing to this year's excavation area, which Sayers calls the "crest." About a dozen students crouch over one-meter squares with trowels, buckets, and brushes. They are removing soil one centimeter at a time and sifting it through a double layer of screens to capture small artifacts. The process is critical for these maroon sites, which typically have few artifacts. No natural rocks are present in the swamp and maroons scoured the area for anything leftover from previous inhabitants.

Cynthia Goode, the doctoral student who guided me in with the team, opens a bag containing her finds from the previous day, taken from a depth of about three centimeters. An irregular lump about the size of a fingernail is a piece of handmade ceramic and a thin piece of light-colored stone is a quartzite flake created during tool-making. There's also a piece of lead shot and an iron nail covered in corrosion. For this site, it's quite a haul. Goode chose American University because of the Dismal Swamp project and hopes to continue it by excavating outside the swamp in now-developed areas, where logging began sometime around 1800 when the canal was built, an act that changed the dynamics of maroon and swamp life forever.

"We're trying to figure out to what extent the maroons may have communicated with these ‘edge' groups," she says. The goal is "testing the model of maroon settlement in areas that are outside the swamp, where slaves would have been logging."

In a nearby area called the "north plateau," graduate student Jordan Riccio is working on a telling indentation. It appears that a round post sat here in a hole lined with ancient Native American ceramic pieces, of the Croaker Landing style (1200–800 b.c.). Under normal circumstances, these pieces would be far deeper in the soil; their presence so near the surface indicates they were found and reused by later residents, probably maroons. Nearby, a dark soil patch indicates a trench between what appears to be more round postholes. Sayers has seen such trenches between posts throughout the excavation. It's possible Native Americans and maroons both used trenches to stabilize posts for what were likely wattle-and-daub houses.

Riccio has exposed two ceramic pieces aligned with the posthole. One is larger than a golf ball, a significant size for the site. The day after my visit, they find white clay tobacco pipe pieces here. But overall, the scarcity and small size of the artifacts attest to the nonmaterialistic nature of the settlements and form a significant pillar of Sayers' theories about maroon culture. An escaped slave would have been aware that there was little chance of avoiding recapture once he or she left the swamp to acquire supplies. Sayers believes the maroons developed a sense of pride and self-containment by resisting the exterior world's values and materialistic culture.

"How that translates on the ground is that we're not going to find many outside-world objects," he says. "The materials I expect to find are those available in the swamp, a lot of organic materials, animal byproducts, plants, or baskets, [though] I haven't found much preserved wood. On the flip side, the indigenous Americans had used these areas for thousands of years, so there was some mining for stuff that was already there." Once they had these items, Sayers says, they used and reused them until almost nothing remained. Even flakes of stone that resulted from sharpening a prehistoric point would be used, as would any man-made object. For example, excavations have uncovered reused pieces of lead shot, gunflint, glass, and chipped stone, as well as a reworked projectile point. This consistent reuse of materials is another distinction of the site.

In the Dismal, traces of settlement are ephemeral. "It could reflect shortness of time of use. These people had such a low-impact footprint, it's just not the kind of feature that historical archaeologists are used to seeing," Sayers says. "I've worked on sites throughout the country and this really is unique. Some might find it boring—here's a collection of stuff, and it's all the size of a penny—but the signature makes it fascinating because it's so connected with their community and how they ran things.

"If they found a bottle, and it broke, they are going to use the pieces. You're not going to have a whole bottle thrown into a pit. If they acquire a white clay pipe, and a chip comes off the bowl, they're going to use it. Same if the stem breaks."

The scarcity of artifacts means that excavations will remain problematic and interpretation will depend on a larger context. "The Dismal Swamp is acidic and wet," says Warren Perry, anthropologist and director of the Archaeology Laboratory for African and African Diaspora Studies at Central Connecticut State University. Maroons, Perry adds, "are in these places so people don't find them. You're going to have limited artifacts. People aren't going to build big towns, because that will get you caught. In maroon sites in Jamaica, there's a lot more material, but still not a bunch."

"We see sites themselves as artifacts," he continues. "The location and the distribution of these sites across the landscapes begin to tell us something."

Sayers believes maroon culture underwent significant changes after the canal projects began, leading to logging inside the swamp as well as commerce outside it. The Dismal Swamp Canal Company incorporated in 1784, and laborers were hired freedmen as well as slaves commissioned from landowners so that work could begin in 1793. The next 12 years brought changes to the maroon communities, as some people assumed jobs on the canal and moved away. Other canal laborers may have temporarily lived in maroon settlements. Sayers and others believe that from this time forward, contact between maroons and the outside world increased. As more logging for cypress shingles took place in the swamp, maroons may have exchanged work for goods with companies that overlooked their fugitive status. Eventually the communities dwindled, so that after the Civil War, they were mostly deserted. A few hermits, living in the occasional cabin,

may have remained.

What they left behind—the nails, glass fragments, and shadow cabin outlines—will lead to a fuller picture of this unique American resistance movement. Specifically, this work might be able to tell us more about how the escaped slaves cooperated with their Native American swamp neighbors, how they fought off armed militias that came searching for them, and how they managed to survive for decades in this mysterious place.

The Great Dismal Swamp Landscape Study will change the way we think about runaway slave culture in the South—and around the world. Traditionally, little work has been done on these maroon swamp communities, but they are pervasive in the region: New Orleans and the swamps of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina have signs of maroon life. Yet they have been largely excluded from study, in part because they are difficult to reach and the artifacts so scarce. Such communities have been much better examined around the world, and their historical significance noted. For instance, in Jamaica in 1740, the British freed maroons and gave them 2,500 acres, as long as they returned future escaped slaves. Revolutionary maroons in Haiti established a nation in 1804, and maroons in Suriname gained sovereign status in the 1800s after attacking nearby plantations.

While the American maroons never succeeded in claiming freedom for themselves in that way, there are commonalities with other refugees around the world, such as establishing a resistance community in thick jungles, rugged terrains, and difficult surroundings. "This project is fitting into that global view," Sayers says. "But in North America, there's not as much discussion of maroons. You talk about runaways, but it's fragmented." For instance, the Underground Railroad was a maroon movement, but is often considered apart from these other maroon efforts. It's both glorified and separated. Sayers asserts that this is because of the involvement of benevolent white people. "We need to start thinking of processes such as the Underground Railroad as part of this global marronage," he says. Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman should be considered key maroon figures. As a step in connecting them, the Dismal became the first National Wildlife Refuge to be officially designated a link in the "Underground Railroad Network to Freedom" in 2003. A new public exhibit at the refuge is expected to open in fall 2011.

"The Underground Railroad is lauded, while maroons remain nameless fugitives," Sayers says. "In the traditional view, it's the flight that's important, not the lives that maroons led after flight."

According to Perry, Sayers' work will debunk misconceptions about slavery—specifically that resistance was limited or that slaves only escaped with the help of benevolent whites. Instead, he says, refugee communities existed throughout the region. "We have to get away from the idea that they are few and far between," Perry says. "It's much more prevalent than we thought."

While this dig and others to come could eventually give us a better idea of the lives of maroons, much will remain a mystery. Sayers says he's yet to find descendants of these swamp dwellers, who may know the names or stories of some refugees. Their survival depended on their ability to disappear, so our understanding of them may always be partial, hidden by the extraordinary—and welcoming—secrecy of the Dismal.