The 100-foot-high, oval-shaped citadel of Erbil towers high above the northern Mesopotamian plain, within sight of the Zagros Mountains that lead to the Iranian plateau. The massive mound, with its vertiginous man-made slope, built up by its inhabitants over at least the last 6,000 years, is the heart of what may be the world’s oldest continuously occupied settlement. At various times over its long history, the city has been a pilgrimage site dedicated to a great goddess, a prosperous trading center, a town on the frontier of several empires, and a rebel stronghold.

Yet despite its place as one of the ancient Near East’s most significant cities, Erbil’s past has been largely hidden. A dense concentration of nineteenth- and twentieth-century houses stands atop the mound, and these have long prevented archaeologists from exploring the city’s older layers. As a consequence, almost everything known about the metropolis—called Arbela in antiquity—has been cobbled together from a handful of ancient texts and artifacts unearthed at other sites. “We know Arbela existed, but without excavating the site, all else is a hypothesis,” says University of Cambridge archaeologist John MacGinnis.

Last year, for the first time, major excavations began on the north edge of the enormous hill, revealing the first traces of the fabled city. Ground-penetrating radar recently detected two large stone structures below the citadel’s center that may be the remains of a renowned temple dedicated to Ishtar, the goddess of love and war. There, according to ancient texts, Assyrian kings sought divine guidance, and Alexander the Great assumed the title of King of Asia in 331 B.C. Other new work includes the search for a massive fortification wall surrounding the ancient lower town and citadel, excavation of an impressive tomb just north of the citadel likely dating to the seventh century B.C., and examination of what lies under the modern city’s expanding suburbs. Taken together, these finds are beginning to provide a more complete picture not only of Arbela’s own story, but also of the growth of the first cities, the rise of the mighty Assyrian Empire, and the tenacity of an ethnically diverse urban center that has endured for more than six millennia.

Located on a fertile plain that supports rain-fed agriculture, Erbil and its surrounds have, for thousands of years, been a regional breadbasket, a natural gateway to the east, and a key junction on the road connecting the Persian Gulf to the south with Anatolia to the north. Geography has been both the city’s blessing and curse in this perennially fractious region. Inhabitants fought repeated invasions by the soldiers of the Sumerian capital of Ur 4,000 years ago, witnessed three Roman emperors attack the Persians, and suffered the onslaught of Genghis Khan’s cavalry in the thirteenth century, the cannons of eighteenth-century Afghan warlords, and the wrath of Saddam Hussein’s tanks only 20 years ago. Yet, through thousands of years, the city survived, and even thrived, while other once-great cities such as Babylon and Nineveh crumbled.

Today Erbil is the capital of Iraq’s autonomous province of Kurdistan. The citadel remains at the heart of a thriving city with a population of 1.3 million, made up mostly of Kurds, and a boomtown economy, thanks to a combination of tight security and oil wealth. During the twentieth century, the high mound fell into disrepair as refugees from the region’s conflicts replaced the town’s established wealthy families, who moved to more spacious accommodations in the lower town and suburbs below. The refugees have since moved to new settlements, and efforts are currently under way to renovate the deteriorating nineteenth- and twentieth-century mudbrick dwellings and twisting, narrow alleys. A textile museum opened in a restored, grand, century-old mansion in early 2014, and work rebuilding the adjacent nineteenth-century Ottoman gate, which sits on much more ancient foundations, is nearing completion. The conservation work is also giving archaeologists the chance to dig into the mound—which has just been declared a World Heritage Site—once so wholly inaccessible. “Erbil has been largely neglected, and we know so little,” says archaeologist Karel Novacek of the University of West Bohemia in the Czech Republic, who conducted the first limited excavations on the citadel in 2006. Extensive long-term excavations are not feasible in Erbil. Nevertheless, Novacek, MacGinnis, their Iraqi colleagues, and archaeologists from Italy, France, Greece, Germany, and the United States, are using old aerial photographs, Cold War satellite imagery, and archives of ancient cuneiform tablets to pinpoint the best spots to dig in order to take advantage of this first real opportunity to examine Erbil’s past.

Although the citadel has played an important role in the Near East for millennia, knowledge of the site has been remarkably limited because so little archaeology has been done there and in the surrounding area. Only a few pieces of 5,000-year-old pottery found on the citadel attest to the existence of ancient Arbela. And although the greatest quantity of information about the city’s appearance, inhabitants, and role in the region derives from the Assyrian period, almost all of the evidence we have comes from texts and artifacts found at other sites.

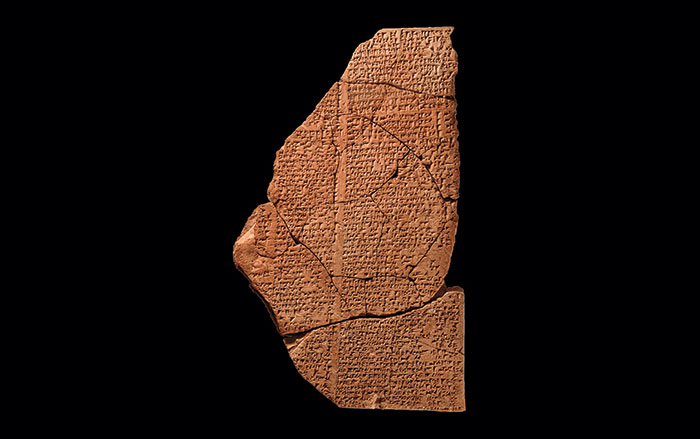

The first mention of Arbela is found on clay tablets dating to about 2300 B.C.. They were discovered in the charred ruins of the palace at Ebla, a city some 500 miles to the west in today’s Syria that was destroyed by the emerging Akkadian Empire. These tablets, some of the thousands found at the site in the 1970s, mention messengers from Ebla being issued five shekels of silver to pay for a journey to Arbela.

A century later, the city became a coveted prize for the numerous ancient Near Eastern empires that followed. The Gutians, who came from southern Mesopotamia and helped dismantle the Akkadian Empire, left a royal inscription that boasts of a Gutian king’s successful campaign against Arbela, in which he conquered the city and captured its governor, Nirishuha. Nirishuha, and possibly other inhabitants of Arbela as well, was likely Hurrian. Little is known about the Hurrians, who were members of a group of either indigenous peoples or recent migrants from the distant Caucasus. This inscription provides our first glimpse into the identities of the multiethnic people of Arbela.

In the late third millennium B.C. the southern Mesopotamian city of Ur began to build its own empire, and sent soldiers 500 miles north to subdue a rebellious Arbela. Rulers of Ur claimed, in contemporary texts, that they had smashed the heads of Arbela’s leaders and destroyed the city during repeated and bloody campaigns. Other texts from Ur record beer rations given to messengers from Arbela and metals, sheep, and goats taken to Ur as booty. Three centuries later, in an inscription said to have come from western Iraq, Shamshi-Adad I, who established a brief but large empire in upper Mesopotamia, tells of encountering the king of Arbela, “whom I pitilessly caught with my powerful weapon and whom my feet trample.” Shamshi-Adad I had the monarch beheaded.

By the twelfth century B.C., Arbela was a prosperous town on the eastern frontier of Assyria, which covered much of northern Mesopotamia. Over the next centuries, the Assyrians, a tight-knit trading people who built an independent kingdom just to the west and south of Arbela, became the largest, wealthiest, and most powerful empire the world had seen. This empire eventually subsumed the city, which became an important Assyrian center, although the city’s population seems to have retained a mix of ethnicities throughout this long era, which lasted until 600 B.C.

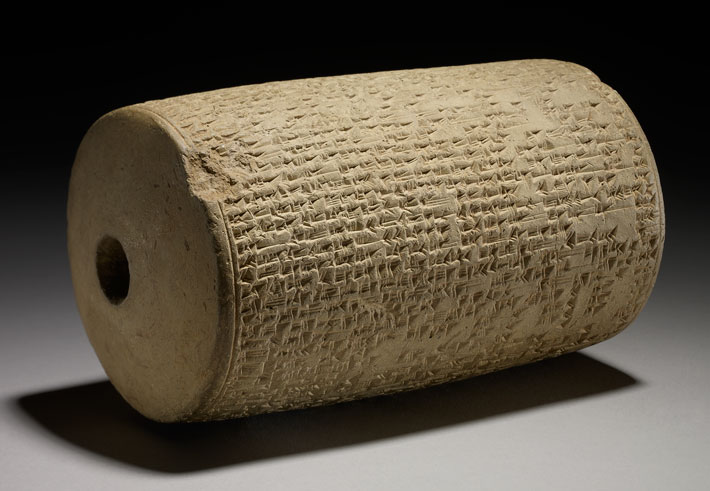

At the core of Arbela’s religious, political, and economic life in this period was the Egasankalamma, or “House of the Lady of the Land.” Assyrian texts mention the temple, dedicated to Ishtar, as early as the thirteenth century B.C., though its foundations likely rest on even older sacred structures. In Mesopotamian theology Ishtar was the goddess of love, fertility, and war. Martti Nissinen of the University of Helsinki has closely examined the 265 references to the goddess in Assyrian texts, and he suggests that the roots of this version of Ishtar may lay deep in the ancient Hurrian pantheon.

The Assyrian Empire reached its height in the seventh century B.C., when the kings Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal ruled the region, including Arbela. Contemporary Assyrian texts describe the Egasankalamma as a richly decorated and elaborate complex where royals regularly came to seek the goddess’ guidance. Esarhaddon claimed that he made the temple “shine like the day,” likely a reference to a coating of a silver-and-gold alloy called electrum that gleamed in the Mesopotamian sun. A fragment of a relief from the Assyrian city of Nineveh shows the structure rising above the citadel walls. Some Assyrian royals may have lived there in their youth, perhaps to keep them safe from court intrigues at the capitals of Nineveh, Nimrud, and Assur in the empire’s heartland. On one tablet Ashurbanipal says, “I knew no father or mother. I grew up in the lap of the goddess”—Ishtar of Arbela.

Under the Assyrians, Arbela was a cosmopolitan gathering place for foreign ambassadors coming from the east. “Tribute enters it from all the world!” says Ashurbanipal in one text. A governor oversaw the city’s administration from a sumptuous citadel palace where taxpayers brought copper and cattle, pomegranates, pistachios, grain, and grapes. Arbela’s own inhabitants were a diverse mix that likely included those forcibly resettled by the Assyrian state, as well as immigrants, merchants, and others seeking opportunity in a city that rivaled the Assyrian capitals in stature. “Arbela at this time was a multiethnic state,” says Dishad Marf, a scholar at the Netherlands’ Leiden University. Names of its citizens found in Assyrian texts are Babylonian, Assyrian, Hurrian, Aramain, Shubrian, Scythian, and Palestinian.

Assyrian royalty also lavished gifts and praise on Arbela and its patron deity. “Heaven without equal, Arbela!” proclaims one court poem found in Nineveh’s state archives. The poem also describes Arbela as a place where merry-making, festivals, and jubilation echoed in its streets, and Ishtar’s shrine as a “lofty hostel, broad temple, a sanctuary of delights” resounding with the music of drums, lyres, and harps. “Those who leave Arbela and those who enter it are happy,” the hymn concludes. Not all, however. The Nineveh relief depicting Arbela includes a king, likely Ashurbanipal, pouring a libation over the severed head of a rebel from Arbela. According to ancient records, the king had the surviving agitators chained to the city gates, flayed, and their tongues ripped out.

B.C. stone relief found at Nineveh. " data-image-credit="(Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)" srcset="https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-4.jpeg 710w, https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-4-300x237.jpeg 300w" sizes="(max-width: 710px) 100vw, 710px" />

B.C. stone relief found at Nineveh. " data-image-credit="(Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY)" srcset="https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-4.jpeg 710w, https://archaeology.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/image-4-300x237.jpeg 300w" sizes="(max-width: 710px) 100vw, 710px" />After so many centuries of regional domination, the Assyrians’ fall was sudden and swift—and Arbela proved to be the sole surviving major settlement. A coalition of Babylonians and Medes, a nomadic people who lived on the Iranian plateau, destroyed the Assyrian capitals in 612 B.C. and scattered their once-feared armies. Arbela was spared, perhaps because its population was in large part non-Assyrian and sympathetic to the new conquerors. The Medes, who may be the ancestors of today’s Kurds, likely took control of the city, which was still intact a century later when the Persian king Darius I, third king of the Achaemenid Empire, impaled a rebel on Arbela’s ramparts—a scene recorded in an inscription carved on a western Iranian cliff around 500 B.C.

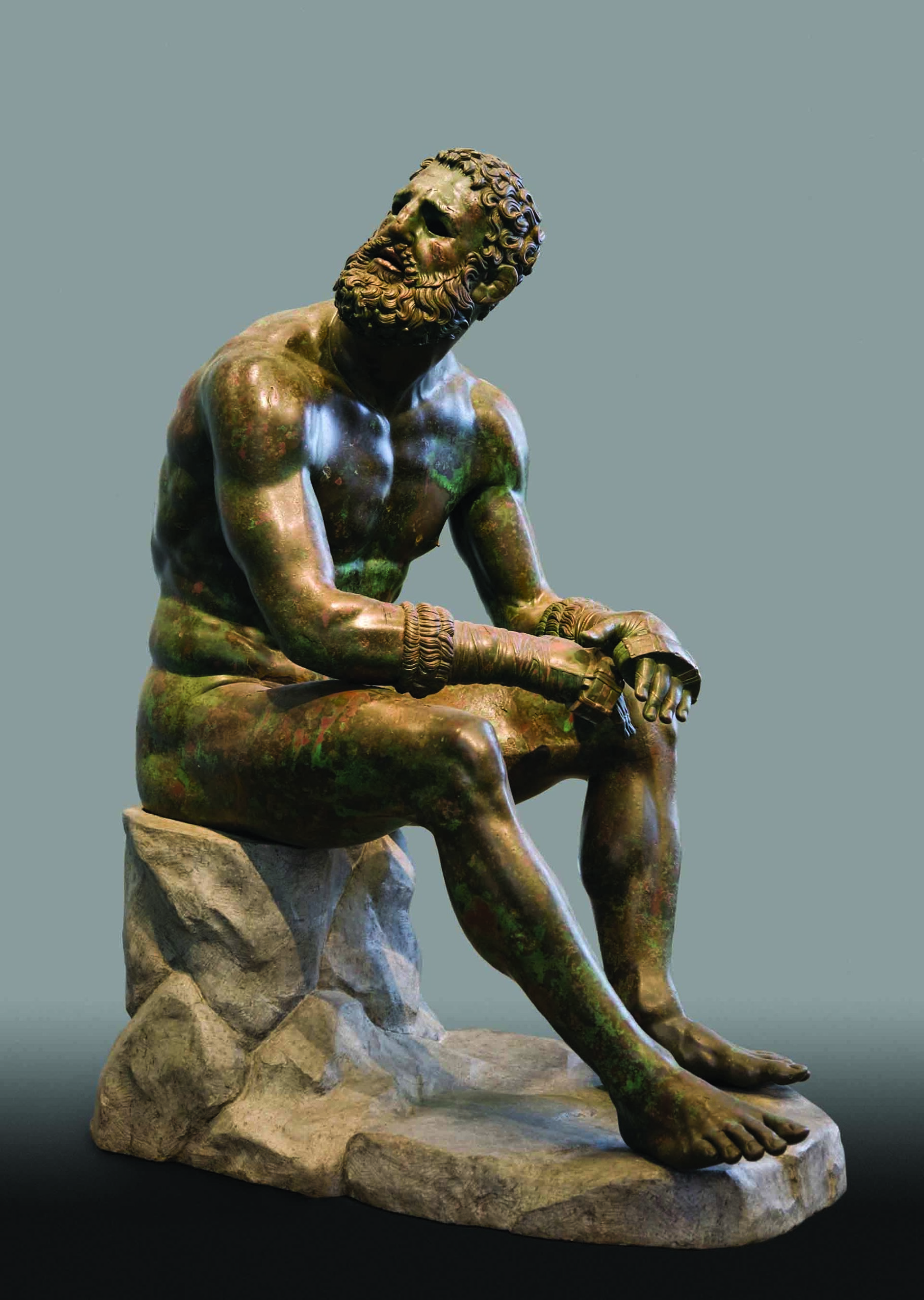

By the fourth century B.C., the Achaemenid Empire stretched from Egypt to India. In the fall of 331 B.C., on the plain of Gaugamela to the west of Arbela, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great fought the Achaemenid ruler Darius III, routing the Persian army as its king fled. Classical sources say that Alexander pursued Darius across the Greater Zab River to Arbela’s citadel, where historians believe the Persian king had his campaign headquarters. Darius escaped east into the Zagros Mountains and was eventually killed by his own soldiers, after which Alexander assumed the leadership of the Persian Empire, possibly in a ceremony held in Arbela’s temple of Ishtar, whom he may have equated with the Greek warrior-goddess Athena.

A team from Sapienza University of Rome recently used ground-penetrating radar to examine what lies under the center of the citadel, and found intriguing evidence of two structures buried some 50 feet below the surface. “This is the rubble of large stone buildings,” says Novacek, who believes this material may sit in late Assyrian levels, and could prove to be remnants of the electrum-coated temple.

However, excavating a 50-foot-deep trench in the center of a high mound poses immense engineering and safety challenges, says Cambridge’s MacGinnis, who is advising the Iraqi-led team. Thus, instead of focusing on the center of the citadel and the possible remains of the temple, the excavators started work last year on the citadel’s north rim with an eye to exposing the ancient fortification walls. At the time, an abandoned early-twentieth-century house had recently collapsed, giving researchers a chance to remove and see beneath the most recent layers. Thus far, 15 feet of debris has been cleared away and investigators have uncovered mudbrick and baked brick architecture, medieval pottery, and a sturdy wall that may rest on top of the original Assyrian fortifications. Next the team will tackle two other small areas nearby before returning to the citadel to attempt the much trickier task of delving into the mound’s central interior.

Novacek, meanwhile, has turned his attention to the ancient city that grew up in the citadel’s shadow. “The lower town, which has been barely investigated, is the key to understanding the city’s dynamics,” he says. “Digging there requires a different approach.” Today Erbil’s thickly settled downtown, in fact, hides traces of the ancient site. Novacek is using British Royal Air Force aerial photos taken in the 1950s and American spy satellite images from the 1960s Corona program to look for remnants of the ancient city that survived into at least the middle of the twentieth century. He has found faint outlines of two sets of fortifications. One of these is a modest system probably dating from the medieval era, while the second is a much larger set of structures that likely dates to some time in the Assyrian period, and had been bulldozed to make way for the modern town in the 1960s.

The earlier fortifications include a 60-foot-thick wall that likely had a defensive slope and a moat. The city’s formidable construction, says Novacek, resembles that found at Nineveh and Assur, and places it “unambiguously among Mesopotamian mega-cities.” The layout differs from that in other Assyrian cities, where the walls were rectangular, with a citadel as part of the protective fortifications. Arbela, however, had an irregular round wall entirely enclosing both the citadel and the lower town. That design is more typical of ancient southern Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Uruk—a hint, Novacek says, of Erbil’s ancient urban heritage. “This conjecture desperately needs empirical verification,” he cautions. Yet, if it can be proven, ancient Arbela might rank among the earliest urban areas and challenge the idea that urbanism began solely in southern Mesopotamia.

Novacek is hopeful that parts of the ancient city, such as those discovered by a German Archaeological Institute team, might still lay buried under the shallow foundations of nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings. In 2009, the German excavators uncovered a seventh-century B.C. Assyrian tomb just a short walk north of the citadel. The tomb had a vaulted chamber of baked bricks and three sarcophagi containing the remains of five people, a bronze bowl, lamps, and pottery vessels. Using ground-penetrating radar, the team surveyed a 100,000-square-foot area around the tomb and spotted extensive architectural remains under a low mound mostly covered with modern buildings. The discovery provides the first archaeological evidence of an Assyrian presence in Arbela and begins to confirm the Assyrian court records that mention Arbela as an important city. Yet Novacek worries that the deep foundations of the enormous modern structures being built near the citadel could quickly obliterate Erbil’s ancient past.

Other researchers are looking further afield, outside the city limits. A team led by Harvard University’s Jason Ur began to survey the area around Erbil in 2012. “It’s one of the last broad alluvial plains in northern Mesopotamia to remain uninvestigated by modern survey techniques,” says Ur, who also made use of old spy satellite photographs to identify ancient villages and towns that could then be explored. Examining 77 square miles, the team mapped 214 archaeological sites dating as far back as 8,000 years. One surprise was that settlements from between 3500 and 3000 B.C. contain ceramics that appear more closely related to southern Mesopotamian types than to those of the north. Ur says this may mean that the plain, rather than being peripheral to the urban expansion that took place in cities such as Ur and Uruk, was related in some direct way to the great cities of the south. This evidence further boosts Novacek’s theory that Arbela was, in fact, an early urban center.

The ongoing research of the teams now working in the city is starting to create an archaeological picture of life in Erbil and its environs over the course of millennia. After the Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks were gone, the city went on to serve as a key eastern outpost on the Roman frontier, and was briefly the capital of the Roman province of Assyria. Later it was home to flourishing Christian and Zoroastrian communities under Persian Sasanian rule until the arrival of Islam in the seventh century A.D. Though the city escaped destruction by the Mongols in the thirteenth century—its leaders wisely negotiated surrender—Erbil subsequently slipped into obscurity. When Western explorers arrived in the eighteenth century they dismissed the place as a muddy and decrepit settlement of medieval origin. While Kurdistan’s isolation under the latter part of Saddam Hussein’s reign placed the area off-limits to most outsiders, in the post-Saddam era, Erbil has been set to play an important role in the region. Conflict, however, threatens again.

Amid the archaeologists’ trenches and the mounds of construction materials destined for use in the citadel’s conservation, one family still lives on Erbil’s high mound, near the ancient citadel gate, preserving the city’s claim as the oldest continuously settled place on Earth.