What is it?

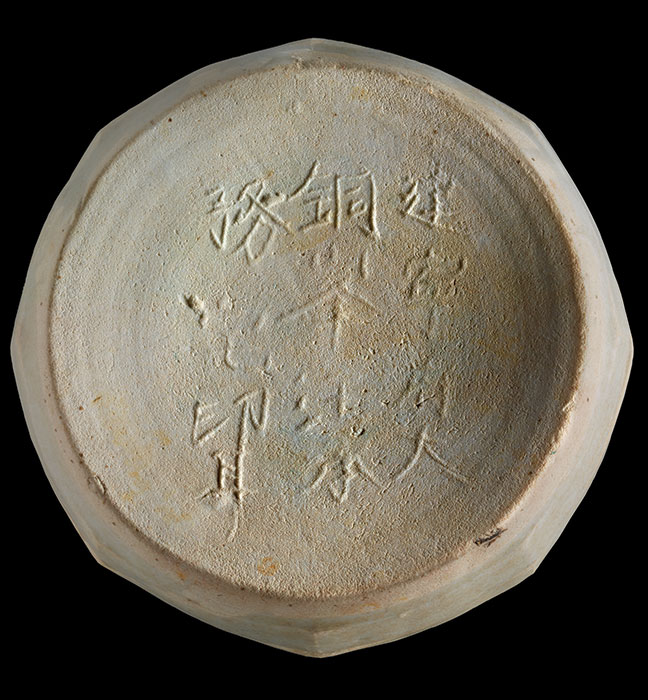

Base of a qingbai-glazed molded box

Culture

Chinese

Date

A.D. 1162-1278

Material

Ceramic

Found

Shipwreck, Java Sea, Indonesia

Dimensions

Diameter 4.48 inches, height 2.12 inches

It may not seem that a single artifact recovered from a ship carrying more than 100,000 objects could dramatically alter scholars’ understanding of a historical period. But sometimes it can make a world of difference.

Qingbai glazing produces a bluish-white tint, and molded ceramic boxes made with this technique were used to hold cosmetics, jewelry, small mirrors, medicine, incense, or ink cakes. They were one of the most commonly exported kinds of ceramics during China’s Song Dynasty (A.D. 960–1279). According to Lisa Niziolek of the Field Museum in Chicago, who studies artifacts recovered from this Java Sea shipwreck, the box, with a peony on the top and an inscription on the bottom, is characteristic of these exports—but with an important exception. The inscription on this box is much longer than is usual and holds one of the keys to redating the wreck.

“Typically, if there is an inscription, it’s short and provides the name of the family workshop where the piece was produced,” says Niziolek. This particular inscription provides not only a surname (Ji), but also a place name, Jianning Fu (present-day Jian’ou in Fujian Province in China), an administrative designation it was given by the Song government. After A.D. 1278, the Yuan Dynasty (A.D. 1271–1368) changed the name to Jianning Lu. This, along with comparative ceramics and new radiocarbon dates, suggests the ship sank about 100 years earlier than initially thought. “Maritime trade had begun to increase at that time,” says Niziolek, “and shift from what had previously been a network of tributary missions to China by various Southeast Asian rulers and envoys to one more focused on open economic trade. This new data begins to help us define the roots of broad-scale, cross-cultural globalization in East Asia.”