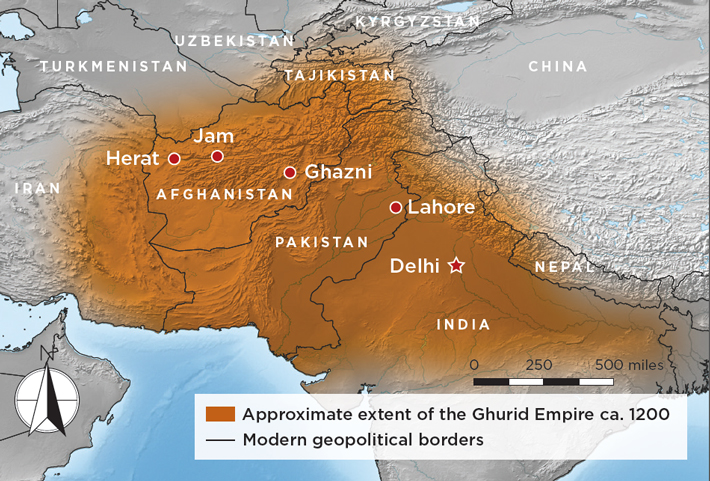

In the remote province of Ghur in western Afghanistan, the Hari and Jam Rivers meet in a narrow valley where mountains tower 7,000 feet high over a seemingly impassable landscape. Far from any urban center, this valley is home to one of the world’s great architectural monuments—a 200-foot-high minaret rising above the valley floor in what seems to be splendid isolation. Built in 1174 of baked brick, the Minaret of Jam is covered in intricate geometric brickwork, with verses of the Koran rendered in blue-glazed tiles. It is one of the few surviving buildings commissioned by the Ghurid sultans, a seasonally nomadic dynasty that, from 1148 to 1215, ruled an empire that at one point stretched from eastern Iran to the Bay of Bengal. “They are like a flare that burst from nowhere,” says David Thomas, a research associate at La Trobe University and director of the Minaret of Jam Archaeological Project (MJAP). “They knock over previously established dynasties, amass territory all the way to northern India, and then, bang, they are gone again.” Though today they are obscure even to many scholars, the Ghurids had a major impact on the trajectory of history in a region whose inhabitants continue to play a geopolitical role that belies their remote location. The recently published work of MJAP is placing a renewed focus on the Ghurids and providing an opportunity to reassess the history of a little-known people.

Thomas’ research is based on fieldwork he and his team conducted at Jam in 2003 and 2005. Extensive looting had exposed large areas of archaeological deposits to the elements, and officials tasked MJAP with investigating trenches that had already been illegally dug. The team’s work enabled them to confirm, after many years of speculation, that the site of Jam was Firuzkuh, the Ghurid Dynasty’s summer capital. “When you look at the site, it seems there is nothing there apart from the minaret,” says Thomas. “But we’ve been able to marry together archaeological evidence and historical accounts that show this is Firuzkuh, and it gives us new insights into what a medieval nomadic capital looked like.” The site has been inaccessible to researchers since MJAP’s initial work, but Google Earth’s aerial imagery has given Thomas the chance to identify additional possible Ghurid-period sites in the area, and to put Jam in a larger regional context. Analysis of artifacts and samples from the looters’ holes has also given the team a compelling, if still incomplete, picture of life in the Ghurid summer capital, whose international reach and flourishing economy suggest this narrow valley in remote Afghanistan was once an important center. “It’s not what we would expect a capital city to be like today,” says Thomas. “But it can tell us a lot about who the Ghurids were, and how they thought about power.”

After the Arab conquest of Central Asia began in the seventh century, most Persian-speaking and nomadic Turkic-speaking peoples in the area quickly converted to Islam. One notable exception were the pagan inhabitants of Ghur. Medieval Islamic sources describe them as hardy mountain folk who spoke a dialect of Persian and lived in isolation on the eastern edge of the Islamic and Persian worlds in the largest non-Muslim enclave in the Islamic world. By the eleventh century, however, a Turkic dynasty known as the Ghaznavids had managed to bring Ghur to heel. Islamic missionaries ventured into the mountains and converted the Ghurids. By the 1140s, the power of the Ghaznavids was on the wane, and an upstart branch of Ghurids from the Shansabanid tribe came to prominence. In 1148, a Shansabanid sultan led an army against the Ghaznavid capital of Ghazni, putting the city to fire and earning the sobriquet “World Burner.” From there, the Ghurids expanded east and west, eventually establishing secondary capitals in the then-obscure city of Delhi on the northern Indian plain, and in the cities of Herat, in modern Afghanistan, and Lahore, in present-day Pakistan. Unlike other medieval Islamic dynasties, the Ghurids had corulers, and power was not inherited by descendants, but shared by multiple sultans who set up court in different locations throughout the empire. The senior sultans stayed in the Ghurid heartland, making their summer capital at Firuzkuh. They sponsored a building program that included erecting mosques, mausoleums, and madrassas, or Islamic schools, across what is now Afghanistan.

Their empire was short-lived. In 1199, people rioted in Firuzkuh, protesting the sultan Ghiyath al-Din’s conversion from a conservative sect to a more moderate strain of Islam. Ghiyath al-Din then moved the capital from Firuzkuh to Herat, where he rebuilt a magnificent mosque, parts of which still stand. But the end was near. In 1215, as political tensions threatened to tear the empire apart, a Turkic people known as the Khwarazmians descended on the fast-disintegrating state. In the Ghurid heartland, the Khwarazmians held sway for less than a decade. By 1222, the armies of Genghis Khan had penetrated the remote mountain fastness of Firuzkuh and destroyed the onetime Ghurid capital, leaving the Minaret of Jam as a solitary testament to the reign of the Ghurid sultans.

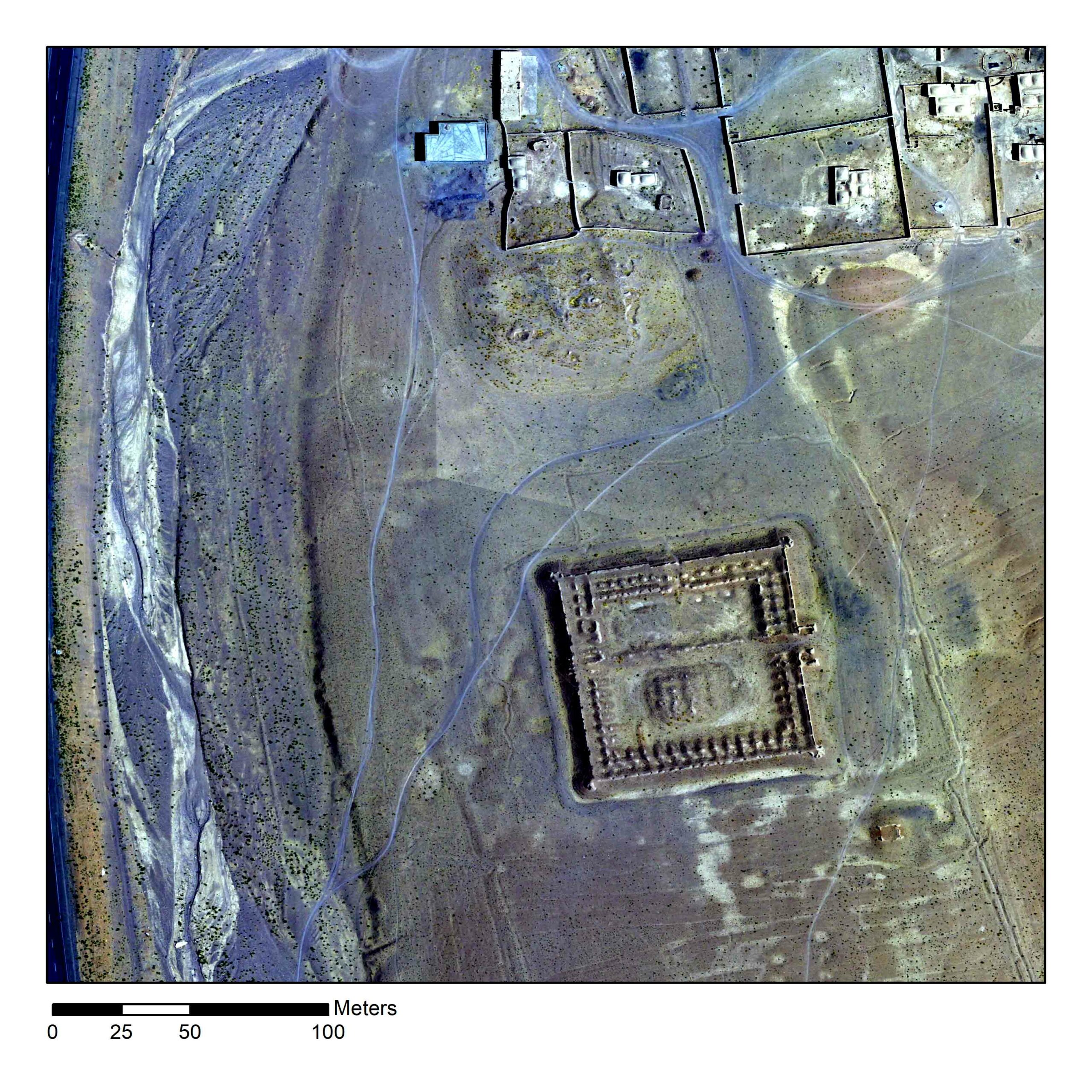

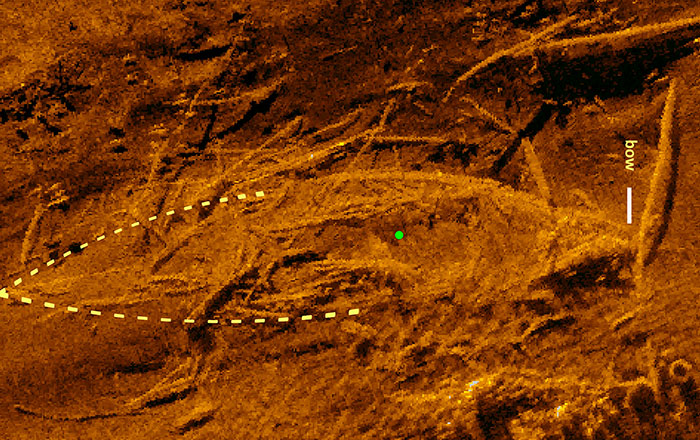

When David Thomas and his codirector, University of Southampton archaeologist Alison Gascoigne, expanded the initial MJAP survey of looters’ holes around the Minaret of Jam in 2005, they turned to recent satellite imagery of the site to guide their work. “The site was pockmarked with robber holes,” says Thomas. “We only had a limited window of time in which to work, so we had to pick what to study carefully.” One area that first drew their attention was a series of holes right next to the minaret.

There they quickly made a discovery that they believe has definitively established that Jam was the summer capital of Firuzkuh. Historical sources recorded that a great flood destroyed a mosque at Firuzkuh around 1200. In a series of holes close to the tower, Thomas and his team discovered the remains of a large brick-paved courtyard that had been covered by river sediment in a single catastrophic event. “It was clear from the stratigraphy that layers of mud and gravel had been deposited by floodwater,” says Thomas. “There was no question that we had evidence for this historical event, making it almost certain the Minaret of Jam was once part of the Firuzkuh mosque.” Thomas notes that, while historical sources do briefly refer to the mosque itself, they make no mention of the minaret. “It’s almost as if, back in the day, a magnificent tower like this was not out of the ordinary. It was just a typical part of the architectural landscape,” says Thomas. “We know there were towers in other Ghurid centers, so chroniclers may just have not considered it remarkable enough to describe.” Reports of a tall tower in the area were first noted in the late nineteenth century by British surveyors, but they were unable to go to the site. In the 1950s, a Belgian archaeologist, acting on a tip from an Afghan historian, visited the tower and publicized it widely.

The Ghurids and their contemporaries often erected towers to commemorate important victories, and it’s possible that the Minaret of Jam was raised to celebrate a military triumph over the Ghaznavids or some other adversary. However, some researchers, including Thomas, believe there may have been a different inspiration behind the construction of the minaret. The main theme of the Koranic verses that decorate the minaret is Mary, the mother of Jesus, who is revered in Islam. There is evidence that a powerful woman in the Ghurid Dynasty commissioned a madrassa to the north of Jam, whose ruins still stand. Given the Minaret of Jam’s emphasis of verses on Mary, perhaps a noblewoman was also responsible for commissioning the tower.

During their surveys and excavations of looters’ holes, Thomas and his team found that the settlement around the minaret was once quite extensive, surprising many longtime observers of archaeology in the region, such as Warwick Ball, former director of the British Institute of Afghan Studies. “Like most, I viewed Jam as an isolated monument,” he says. “Having visited the site, I assumed there was no room for a settlement of any extent.” Previously, most scholars thought if Jam was indeed Firuzkuh, then it functioned as a symbolic center, a capital in name only. “David’s work proved conclusively that there was a city, or at least an urban settlement, associated with the minaret—that it was a capital in practice as well as in name,” says Ball. That discovery led Thomas and his team to speculate about why the Ghurid sultans chose such a rugged and remote spot for such an important center, which would have combined permanent structures with temporary encampments. Thomas notes that, along the Jam River a few miles to the south, there are sections of flat land where Ghurid nobles could have set up their tents with much greater ease. “Maybe there was a personal reason that had to do with the selection of the location. Or maybe they felt safe nestled in this river valley,” says Thomas. “They were an incredibly adaptable and flexible people, and I think you see it in their choice of this valley as their capital, even if we don’t know quite why they made that choice.”

Thomas and his team excavated a series of other looters’ holes located throughout the site to get a sense of how complex the capital was. They found one looters’ hole dug into the middle of a substantial mudbrick house. A niche in the side of the structure still had an oil lamp that had been placed there more than 800 years earlier. “We think there were people in residence at the site year-round, despite the fact that the sultans were only here in the summer,” says Thomas. “It would not have been very hospitable in the winter, but we think there was perhaps a caretaker population that watched over the capital in winter.”

It’s possible that some of the more permanent residents belonged to Firuzkuh’s Jewish population, which left behind a substantial cemetery filled with headstones inscribed with Judeo-Persian text. During the medieval period, and well into the twentieth century, most urban centers in Central Asia had significant Jewish populations. Historical sources also record a Ghurid tradition that bound the Jewish population to the success of the Shansabanid Dynasty. In one of the dynasty’s legendary origin stories, a Shansabanid prince planned a journey to Baghdad to gain the support of the Abbasid caliphs, who then maintained nominal control of the Islamic world. It was said that the prince was aware that his mountain upbringing and rough-and-ready appearance and manners might not place him in good stead at the palace in Baghdad. On the journey he met and sought the advice of a Jewish merchant, who advised him on his attire and suggested ways to improve his manners. The Shansabanid prince then made a successful appearance at the Abbasid court and won support for his claim to the Ghurid sultanate. Thereafter, it was said, Jews were welcome in the Ghurid heartland.

Thomas and his team identified four Jewish headstones, which added to a collection of more than 70 that had been found by Italian researchers in the 1960s. All but six of the headstones recovered thus far memorialize men who lived between 1150 and 1220, the historically recorded period of occupation in Firuzkuh. That there are no headstones from the cemetery belonging to Jewish women suggests to Thomas and his colleagues that the men likely came to the capital without families, and perhaps married local non-Jewish women. The professions listed on the gravestones include goldsmith, teacher, and religious specialist, in addition to more workaday trades. Along with the dates on the gravestones, this suggests a long-lived community had put down roots at Firuzkuh and occupied the town year-round.

In addition, the variety of ceramics recovered from the site show that the prosperous capital was part of a far-flung trade network. Gascoigne, MJAP’s pottery expert, identified fine ware not only from Iran, but also from China. “It’s interesting to see how the population in this incredibly remote area was provisioned,” she says. “Some of this pottery had come a very long way.” The team also found elaborately molded water jars, one of which featured a humorous depiction of a smiling, puffy-cheeked individual. Some of the pottery they collected could have been produced on-site. The team identified the remains of an industrial-sized kiln to the south of the settlement that may have been used to fire pottery, but they were unable to study it in detail. Surrounding the capital was a complex system of mudbrick fortifications, much of which seems to have been designed without an external threat in mind.

Thomas analyzed the views from the still-extant towers, and found that most of them did not command vistas that extended beyond the valley. Rather, many of the towers seem to have been constructed to conduct surveillance of the valley itself. Thomas speculates that the fortifications might have been built in the wake of the religious riots that swept Firuzkuh toward the end of the Ghurid Dynasty’s reign. It’s possible that even after the Ghurid sultan Ghiyath al-Din quit the remote summer capital for Herat, he wanted to keep an eye on his rebellious subjects in Firuzkuh. A network of fortifications intended to monitor threats inside the capital, rather than approaching foes, might have been a result of his concern. The sultan was perhaps right to be preoccupied with the possibility of internal instability. His successor was assassinated in 1215, an event that led to the collapse of the Ghurid Empire. It had lasted less than 70 years in all.

Thomas and his team have been unable to conduct fieldwork since 2005 due to unstable political conditions in the region. Using Google Earth, Thomas has since identified a host of possible sites in central Afghanistan that could date to the Ghurid period, or may have been occupied and repurposed by the Ghurids. In 2014, Thomas and two Afghan colleagues identified an unrecorded tower not far from Jam. But confirming these sites will have to wait for a return to stability, which could be far off. In spring 2019, Taliban units advanced close to Jam and fought troops loyal to the Afghan government before retreating. Eighteen people were reportedly killed during the Taliban attack.

The Minaret of Jam is now listing dangerously and was also recently threatened by heavy spring floods. UNESCO has sponsored conservation work at the site in the past, and intends to continue to do so in the near future if security conditions permit. In the meantime, the work Thomas and his team conducted at Jam remains the most complete study of any Ghurid center in Afghanistan. “The robber holes should never have been dug in the first place,” says Thomas. “But at least we were able to use them to learn more about the Ghurids. The remains at Jam tell us that while they were a tough, resourceful mountain people who needed to watch their backs, here in their heartland, they built a capital fit for a sultan.”