The age of Homer was an age of heroes—Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae, Odysseus, the king of Ithaca, and Nestor, the king of Pylos, among others—whose deeds are chronicled in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Many archaeologists believe that Homer’s tales, despite being composed 500 or more years after the Late Bronze Age events they describe, had roots in a real past. “There’s always a kernel of truth to stories handed down from generation to generation,” says archaeologist Jack Davis. Whether these men were real people is unknown. But the culture they belonged to, which dominated Bronze Age Greece from around 1600 until 1200 B.C.—known as Mycenaean since it was given that name by nineteenth-century scholars—was certainly the model for the poems’ dimly remembered heroes from the deep past.

Over the past century, archaeologists and linguists have largely focused their studies on the Mycenaeans’ place in the early development of later classical Greek civilization. Excavations at Pylos, and at sites all across mainland Greece, have provided a great deal of evidence of the Mycenaeans in their prime. This research has revealed that at their peak they were tied into a world that encompassed most of the eastern Mediterranean, including ancient Egypt, the city-states of the Near East, and the islands of the Mediterranean. One such link, though, stands out as perhaps the most important: a deep connection to the island of Crete, which, in the Late Bronze Age, was inhabited by members of a culture scholars call Minoan after the legendary King Minos, a culture very different from that found on the mainland.

Scholars have long debated the nature of the relationship between the Mycenaeans and the Minoans. This discussion has centered on whether Mycenaean culture, and what is thought of as ancient Greek culture, dating to half a millennium later, was imported from Crete, or was a homegrown phenomenon. But the exceptional discovery of a man’s grave filled with more than 2,000 artifacts just outside Nestor’s palace in Pylos suggests that the concept of competing cultures might obscure a deep interconnectedness. “Archaeologists have a way of cutting the world up into well-bounded cultural entities, but it seems that in the Late Bronze Age new identities were being formed,” says archaeologist Dimitri Nakassis of the University of Colorado Boulder. “There used to be clear lines between the Minoans and the Mycenaeans, but a lot of work now points out that these are our categories, not theirs.”

The extraordinary contents of this man’s grave may be the key to understanding a far more complex development. Scholars are now beginning to believe that the shift from the Minoan to Mycenaean world may not have been a sharp transition achieved through colonization or conquest, but a more complicated process of cultural mixture and communication that only came to an end when mainland Mycenaean culture took over Crete around 1400 B.C. Says Jan Driessen, a Minoan specialist at the Catholic University of Louvain, “There’s no way to overestimate the tomb’s importance.”

In 2015, Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker, both of the University of Cincinnati, were in their third decade of research in and around the palace of Pylos. The palace itself was discovered in 1939 and excavated in the 1950s and 1960s. Davis, Stocker, and their colleagues had been exploring the complex and the area around it since the early 1990s. Archaeologists think that by the thirteenth century B.C. Mycenaean society was highly stratified, with a single ruler, called a wanax, who governed thousands of subjects living in and around his palace. Excavations at Mycenaean sites have traditionally focused on these royal complexes. Since the palace at Pylos can’t be further excavated without damaging its well-preserved floors and walls, Davis and Stocker expanded their investigation, seeing an opportunity to uncover the remains of the town or settlement outside the royal and administrative center, as other researchers had at Mycenae.

Legal delays meant the team wasn’t able to excavate where they had originally planned. “Forty people showed up, and we had nowhere to dig,” says Stocker. Thwarted, they began investigating a stone formation nestled among the olive trees that surround the palace. Although the site was just over 200 yards from the palace’s front gate, Davis says he didn’t have high hopes for the area. He thought it might be the foundation of one of the palace’s outbuildings, or a water storage tank.

As the excavators dug into the site’s beige earth, they uncovered a few stones, and then a few more. Soon they were convinced they had discovered a grave. After days of digging, they uncovered a six-foot-by-three-foot shaft carved out of the hard clay. The first artifact the team found was a bronze vessel whose presence after thousands of years was an indication that the tomb hadn’t been robbed. Over the next six months, Stocker and Davis discovered bronze weapons, finely crafted gold jewelry, carved seal stones, ivory inlays, beads, and much more, all buried with a single individual who, the team estimates, was between 30 and 35 years old when he died. Very early on, they unearthed an as-yet-unconserved ivory plaque decorated with a griffin that gave the man his name—the Griffin Warrior.

During the warrior’s time, in the 1500s B.C., the Mycenaeans generally buried their prominent dead in huge, beehive-shaped structures called tholoi that were easily identified by tomb robbers. Thieves have taken a heavy toll on Mycenaean sites over the millennia, and the winding roads around Pylos are dotted with ruined tholoi, now just empty, stone-lined pits in the midst of sprawling olive groves. In fact, a tholos located near the Griffin Warrior’s grave was damaged and robbed long before archaeologists excavated it in the 1950s, and only a few beads and a handful of small artifacts were found inside the structure. The Griffin Warrior’s grave is a rare undisturbed exception, and Stocker is still amazed at the team’s luck. Not only had the grave escaped the tomb robbers’ notice, if it had been situated just a few feet in any direction, the roots of an olive tree would have penetrated and disturbed it.

The warrior’s solo shaft burial was unusual for his time. Most contemporary Mycenaeans were interred in shared graves, sometimes with up to 20 people in a single grave or tholos. The tombs were periodically reopened and the human remains separated and shuffled around with each new addition to the family crypt. This has made it difficult for archaeologists to distinguish which artifacts were buried with whom. “What’s surprising in the case of the Griffin Warrior is to find a complete example where you know exactly what was deposited with this individual,” says archaeologist John Bennet, director of the British School at Athens.

The sheer number of artifacts stands out, too. Later Mycenaean graves, whether individual or shared, rarely contain riches on the scale of the Griffin Warrior’s. “That much concentration of wealth in a single tomb is shocking,” Nakassis says. “I keep thinking, ‘What are they doing? How do they have all this stuff?’” But the discovery in Pylos is significant not only for the survival, quality, and quantity of its finds, but also because the artifacts are encouraging scholars to reconsider this pivotal era, when mainland settlements such as Pylos were on the rise.

Just 500 years before the Griffin Warrior lived, in the Middle Bronze Age, it would likely have been easy to distinguish a mainlander from a Minoan. Although Crete is separated from the Greek mainland by only about 100 miles, the people who lived on the island in the early second millennium B.C. did not have much in common with their neighbors across the Aegean Sea. By 1900 B.C., a sophisticated culture existed on Crete, boasting palaces built using finely cut stonework known as ashlar, a belief system that featured a central goddess figure and other divinities, and the widespread use of bull imagery in its art, none of which were in evidence at this time on the mainland. Excavations at Minoan sites on the island undertaken over the last century show that, starting in the late third millennium B.C., the Minoans’ trade networks were far more extensive than those of contemporary mainlanders. Artifacts found at such Cretan sites as Knossos include imported stone vases and jewelry from Egypt and the Levant, rare commodities on the mainland at this time. The Minoans further distinguished themselves from the mainlanders by their artistic prowess, particularly with regard to gold- and stonework. Minoan craftsmanship was, for centuries, superior to anything found on the mainland.

Nearly 150 years of archaeological excavations on the Greek mainland and Crete have shown that, beginning around 1600 B.C., the comparatively unsophisticated culture on the mainland underwent a radical transformation. “In time, there’s a blossoming of wealth and culture,” Stocker says. “Palaces are built, wealth accumulates, and power is consolidated in places such as Pylos and Mycenae.” The reasons for this leap forward are unknown. For a few centuries, the mainlanders imitated the Minoans. Pylos was an early Mycenaean power center, and buildings there at the time of the Griffin Warrior resembled the large houses with ashlar masonry found at Knossos on Crete. “There were probably four or five fancy mansions in Pylos at the time of the Griffin Warrior, all very Minoan in style,” Davis says. For example, the mansions had painted walls, a type of artistry pioneered by the Minoans.

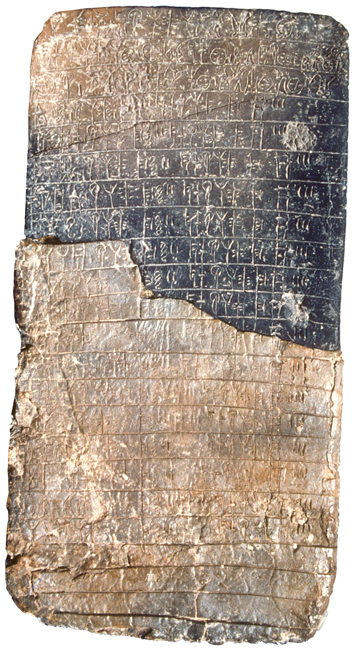

For a time, the Mycenaeans both imported Minoan luxury goods and incorporated Minoan symbols, including the bull, into their own art. The richest Mycenaeans were buried with Minoan luxury goods, while some other graves included locally produced Mycenaean objects, such as painted pottery, that were often excellent-quality copies of Minoan originals. The Mycenaeans also borrowed the Minoan script, called Linear A, and adapted it to their own use; this script is now called Linear B. Mycenaean society, too, began to change shape. What began as a loose collection of small villages became more and more hierarchical, with power concentrated in the hands of the palace-dwelling members of society featured in the works of Homer.

When archaeologists first excavated the later phases of Minoan palaces in the very early 1900s, the direct parallels with sites on the mainland, including similar architecture, artifacts, wall paintings, and pottery, led them to think that mainland Greece might have been little more than a series of Minoan colonies. Minoans, these researchers thought, were the true founders of Mycenaean society, setting up trading outposts and exporting their palace-oriented social structure and distinctive script to a less-sophisticated mainland.

Half a century later, that interpretation was upended. When clay tablets found at Pylos and other sites, including Mycenae, were deciphered in the 1950s, the story was pushed in a completely different direction. Linear B resembled Crete’s Linear A, but recorded an entirely different language—Mycenaean Greek. It became clear that it was related to the language of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and, more distantly, to the other Indo-European languages, from Sanskrit to English. Scholars today can peruse the bureaucratic records left behind in the Palace of Nestor, while Linear A and the language it records remain an impenetrable mystery.

The discovery and decipherment of Linear B led scholars to rethink the relationship between Mycenae and Crete. Not only were the Mycenaeans the true forebears of the ancient Greeks, scholars argued, they were indiscriminate thieves who imported or copied Minoan objets d’art without understanding their meaning or significance. “At the time, most scholars were thinking of hostile takeovers, not cooperative ventures,” says archaeologist Cynthia Shelmerdine of the University of Texas at Austin.

The Griffin Warrior’s grave and its contents are once again changing interpretations of the relationship between the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Much of this has been made possible by the fact that he was buried alone, and that his tomb was discovered undisturbed. This has allowed the team to both study the objects themselves and show how they were originally positioned. Among the thousands of artifacts from the Griffin Warrior’s grave are Minoan-style seal stones of amethyst, carnelian, and agate. Other objects are harder to place, including a sword whose hilt is decorated with tiny gold staples, giving it an embroidered effect, and a boar-tusk helmet, a style of armor that Odysseus wears in Book 10 of the Iliad and that is found on both Crete and the mainland.

Stocker and Davis have spent the last several years building a case that the Griffin Warrior, and the people who buried him, were not just avid collectors of Minoan art but were also highly clued in to its symbolism. “The Griffin Warrior is saying, ‘I’m part of that Minoan world,’” Stocker explains. “There’s a story we can get at with this burial that we haven’t been able to before.” Scholars agree that the grave is more than a random collection of Mycenaean and Minoan objects. “Here, Cretan art is being reused and repurposed in a local context,” says Nakassis. “That tells us there was a strong connection between people living in Pylos and Crete, a highly informed network of goods, and probably of people, across the Aegean. These weren’t unsophisticated rubes who didn’t understand the beauty and grace of the art they were burying.” Instead, they were deliberately creating a reflection of their worldview.

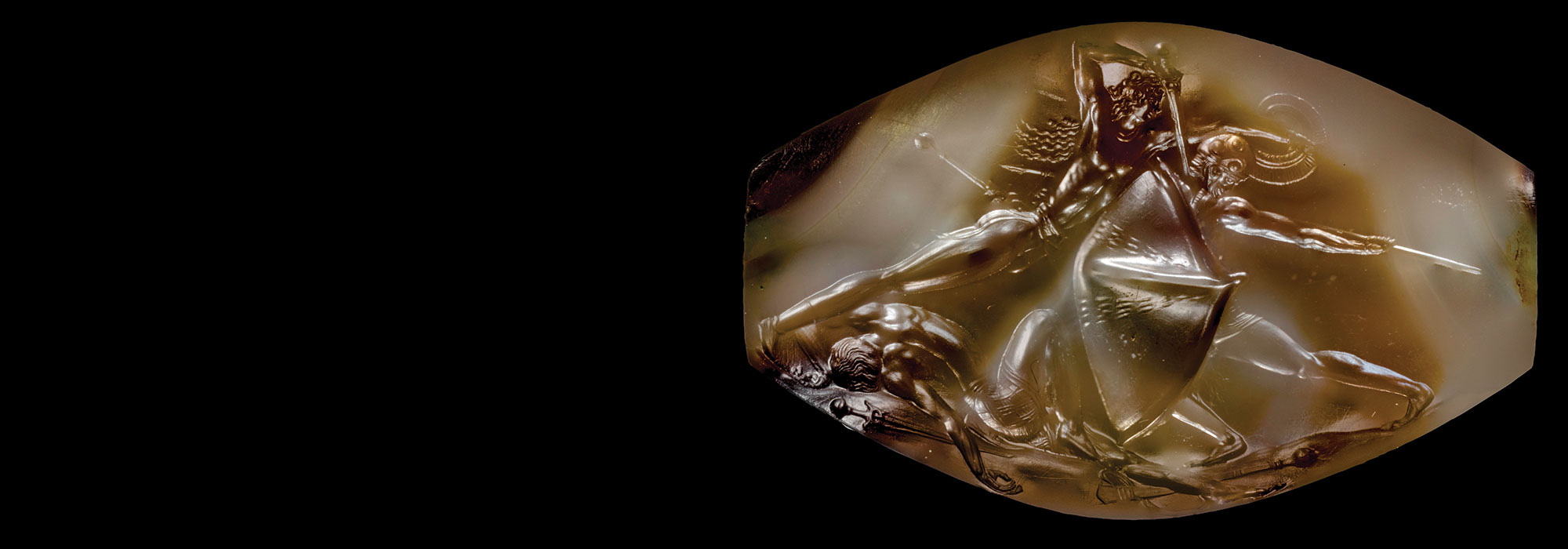

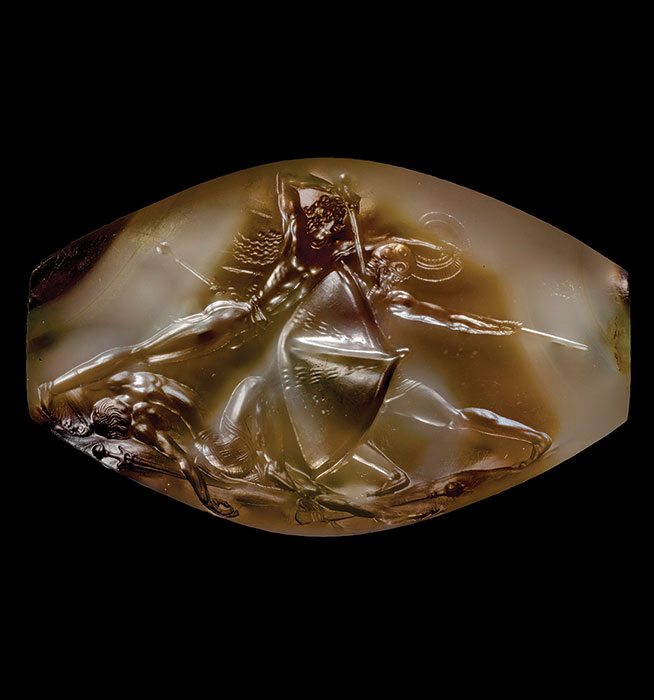

One notable category of objects buried with the Griffin Warrior is seal stones—some 50 of them, made of semiprecious materials. The seal stones, originally used by the Minoans for administrative purposes, are miniature works of art, intricately decorated beyond any functional necessity. In fact, after the stones were cleaned and restored, Stocker’s colleagues made impressions of their designs in putty and found that some of the detail is too small to see with the naked eye, even in the imprints. Many of the stones had been placed on the warrior’s right side, some probably worn as part of bracelets, and others gathered in a bag or pouch that decayed long ago. The most spectacular seal stone, dubbed the Pylos Combat Agate, is just 1.4 inches wide. Davis and Stocker believe that the artist who created this seal stone was Cretan, because there is, thus far at least, no evidence that artisans on the mainland possessed the skill required to create such an object. The stone depicts a leaping warrior stabbing an armored, spear-wielding foe, while another lies dead at his feet. The scene, like those on many of the other seal stones, is echoed by artifacts found in the warrior’s grave, such as the weapons and scepter laid on his left side. “The sword the victor is using is the same as the sword the warrior is buried with,” Davis says. Six ivory combs and a mirror in the grave suggest the warrior was concerned with his grooming, and perhaps had flowing locks similar to those of the stone’s triumphant warrior. Like the agate’s hero, the Griffin Warrior wore a gold necklace. There is also a nearly microscopic seal stone, less than two-hundredths of an inch across, depicted on a bracelet on the warrior’s wrist. The seal stones in the grave were drilled through, as though to accommodate just such a bracelet cord.

The sheer number of carved rings and seal stones reinforces the idea that there was something more than mimicry going on. Driessen says seal stones such as those found in the Griffin Warrior’s tomb were highly individual objects that were used by the Minoans for bureaucratic functions, such as to signal identity on official documents. A Minoan would have had one ring or seal stone, or maybe two—but not 50. “It doesn’t make sense to have fifty seal stones,” Driessen says. “The Griffin Warrior was showing off, or maybe the ones who buried him were showing off. There’s obviously Minoan influence, but I do think some of these objects were not used in the same way the Minoans used them.”

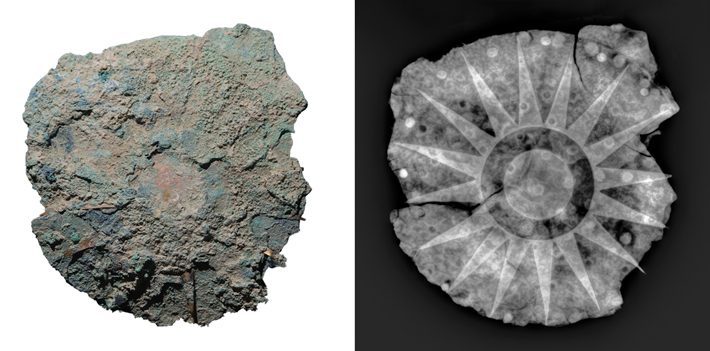

Other objects, too, seem like conscious references to one another. One of four gold rings in the grave shows a Minoan-style bull leaper, echoing a bull’s head once mounted atop a scepter buried nearby. On one seal stone a sun with 16 rays hangs in the sky above two otherworldly creatures with insect-like features, known to scholars of Minoan art as genii. Recent X-rays of a badly corroded bronze breastplate found on the warrior’s legs show that the same 16-pointed star once adorned his suit of armor. “There’s so much evidence that suggests that the Mycenaeans understood Minoan ritual concepts of power,” Davis says. “It seems to us likely that some beliefs originating in Crete had been transplanted intact to Pylos, if not by Minoan missionaries, by converted mainlanders.”

Driessen suggests that the idea of classifying art and artifacts as “Minoan” or “Mycenaean” at this time of cross-cultural ferment may not fully reflect the period’s complexity. For example, he believes that mainlanders might have carved the seal stones themselves, having learned from Minoan artisans, or Cretan artisans may have emigrated to the mainland, bringing familiar iconography to new audiences. The connections between the iconography and artifacts have convinced Stocker and Davis that the Griffin Warrior was an informed consumer of Minoan-style objects, not an indiscriminate looter. Somehow, Stocker says, the Griffin Warrior functions as a kind of bridge between the Minoans and Mycenaeans that provides evidence of just how closely interconnected they were. “There’s symbolic unity among the artifacts. We have things that match, assembled with intentionality,” she says. “It’s not randomly accumulated loot. It reflects a story that’s been purposely acquired.”

Slideshow: A Bronze Age Masterpiece

When University of Cincinnati archaeologists Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis discovered the Bronze Age grave of a man who came to be known as the Griffin Warrior at the site of Pylos in Greece, they could never have imagined that they would eventually recover more than 2,000 artifacts from the burial. In addition to the ivory plaque bearing the half-lion, half-eagle mythical beasts that gave the warrior his name, they found gold rings, bronze weapons, ivory combs, bronze mirrors, and semi-previous seal stones. The tiny gem, known as the Pylos Combat Agate, is decorated with some of the finest carving and most evocative imagery ever seen on a seal stone from the ancient Mediterranean world.