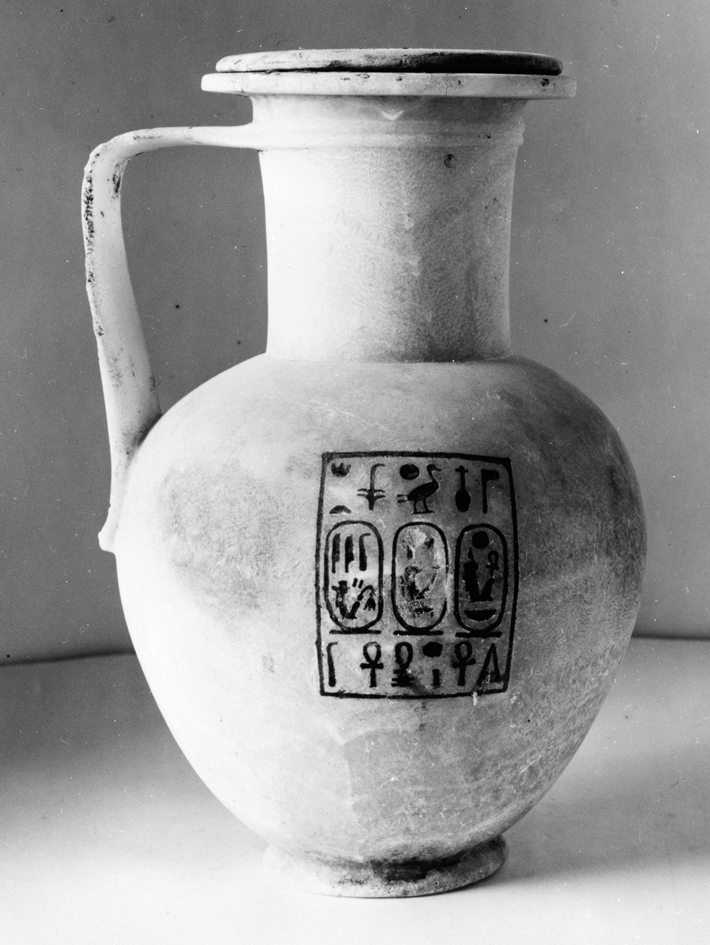

In the century since archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb and revealed its magnificent contents to the world, scholars and enthusiasts alike have been fascinated by the insights they provide into the life of a powerful Egyptian ruler more than three millennia ago. By studying some of the more unassuming items in the tomb’s inventory—a set of 11 alabaster vessels—Egyptologist Martin Bommas of Macquarie University has found evidence that Tutankhamun himself also took a keen interest in his country’s past. Bommas says these vessels were originally used by some of Tutankhamun’s illustrious predecessors, whose names are inscribed on them: the pharaoh Thutmose III, who reigned more than a century before Tutankhamun, as well as the boy king’s grandparents Amenhotep III and Tiye.

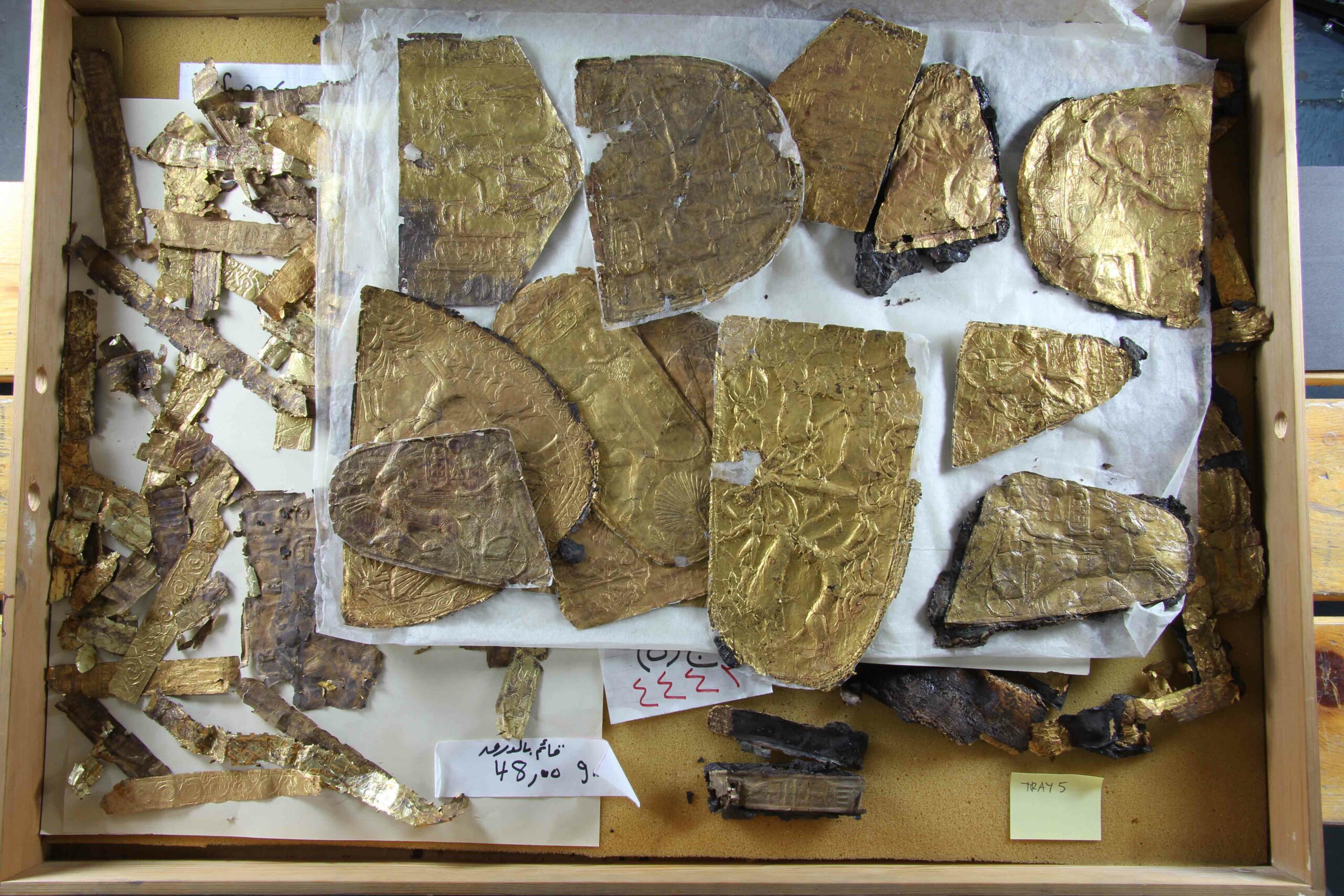

The vessels held emulsions, creams, and oils, residues of which were still present when Carter opened the tomb in 1922. “These were not artifacts that you put on your mantelpiece, they were in daily use,” says Bommas. “The interesting thing is they were restored over a period of time, perhaps even in Tutankhamun’s lifetime.” Given that such vessels could have been made quite cheaply, the question is why Tutankhamun didn’t request new pots inscribed with his own name. Bommas believes the young pharaoh opted to use these antiquated objects as a way of surrounding himself with the aura of history. “At some point, as part of his education, Tutankhamun would have asked, ‘Who were my forefathers? Who was my granddad?’” says Bommas. “And they would have looked through the palaces and collected the vessels and said something like, ‘This is the pot that Thutmose III used after his Euphrates campaign.’ This would have been a wonderful way for Tutankhamun to link with his past.”

In particular, Bommas suggests, the vessels may have been a way for Tutankhamun to reconnect with traditions that held sway before his father, the pharaoh Akhenaten, shifted Egypt’s religious focus from the creator god Amun-Ra to the god of light, Aten. As Tutankhamun made clear in the so-called Restoration Stela, found in the Karnak Temple, Akhenaten’s religious experiment had been a disaster for the country. “The temple and cities of the gods and goddesses…were fallen into decay and their shrines were fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass,” he writes. According to Bommas, “The problem for Tutankhamun was to reconnect with the time before Atenism. There was no other way for him but to study history, and these vessels informed him about the importance of the Egyptian past.”