More than 15,000 years ago, a group of hunter-gatherers in northern Spain killed a lion and brought it home. Cave lions (Panthera spelaea) had roamed Europe for at least 400,000 years, but by this time, their numbers were declining as they were forced to compete for prey with an increasing human population. The lion must have been a great prize. Rather than cut up the feline for food at their cave’s entrance, as they did with their other prey, the people carried parts of the huge animal 425 feet into the cave, now called La Garma, to an area known as the Lower Gallery. There, archaeologists discovered nine of the animal’s phalanges, the part of the paw to which the claws are attached.

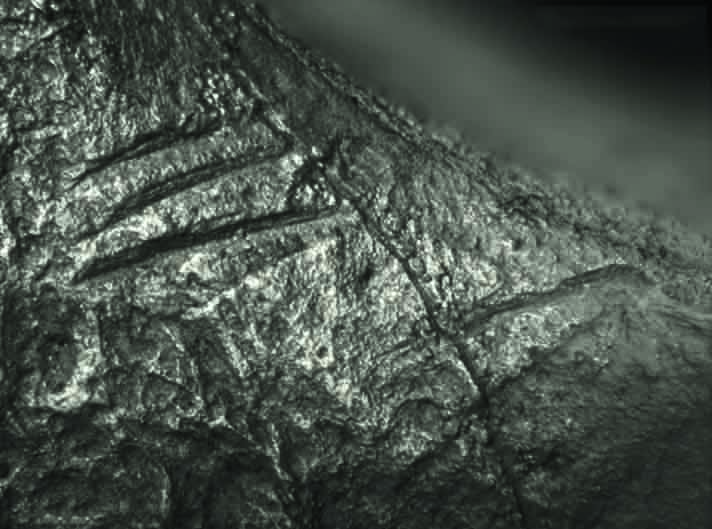

The faunal remains in La Garma’s Lower Gallery are uniquely well preserved and provide rare evidence of the daily lives of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers and of the animals they interacted with. More than 4,000 mammal bones and fragments have been uncovered in the Lower Gallery, but none more fascinating than the lion’s. Researchers studying the big cat’s phalanges determined that eight of the nine bones had cut marks or scrapes, evidence that the lion had been butchered. Archaeozoologist Marián Cueto of the Autonomous University of Barcelona thinks this was done by someone who had extensive experience cutting up animals—including those with anatomy similar to that of lions, such as bears and foxes—to use for food or to make garments or shelters.

The location of the lion’s remains deep in the cave, in an area where archaeologists also found the remains of two brightly feathered ducks and numerous bone objects engraved with animal figures, as well as seashell necklaces, has led Cueto to conclude that the lion wasn’t killed for food. Instead, she believes butchering it was part of some sort of ritual practice. “Hunting a lion is not an easy task, and achieving this feat, and saving some proof such as the lion’s skin with its paws and claws, must have had special significance,” Cueto says. “Hunting lions in the Paleolithic period—which certainly was not common—is important for what it tells us about the richness and complexity of the symbolic world of these human groups.”