For thousands of years beginning at least 10,000 years ago, a population of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers sharing the same genetic lineage lived in what is now Denmark. Then, around 5,900 years ago, they were replaced wholesale by Neolithic farmers with roots in Anatolia (modern Turkey). Just a millennium later, these farmers were, in turn, completely supplanted by herders known as the Yamnaya, whose origins can be traced back to the southern Russian steppe. A study that involved sequencing the genomes of 100 people who lived in Denmark between 10,500 and 3,200 years ago revealed these dramatic population changes.

The general pattern of hunter-gathers giving way to farmers who then gave way to herders is known to have unfolded throughout Europe. In this case, however, researchers were able to obtain an unusually precise view of population dynamics. “We had access to a lot of skeletons from the same small area and could place them in time with very fine-scale resolution because they were all radiocarbon dated,” says Morten Allentoft, an evolutionary biologist at Curtin University. “As a result, we could understand in great detail how these population turnovers happen through time.”

In both instances when new groups arrived in Denmark, researchers found, the existing population was completely uprooted. The Neolithic farmers in Denmark had some Mesolithic hunter-gatherer ancestry, but this turned out to have been acquired over generations as they mixed with hunter-gatherers on their way through central Europe. Likewise, the herders who replaced the farmers in Denmark had some Neolithic ancestry, but they had brought it with them from the steppe. “What I found most surprising is how complete and fast these turnovers are,” says Anne Birgitte Nielsen, a paleoecologist at Lund University.

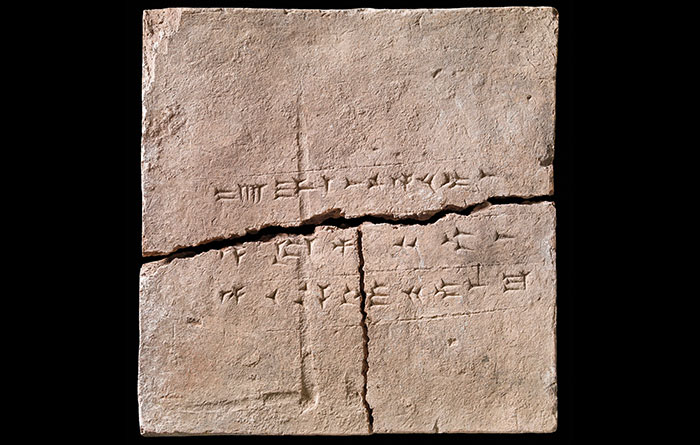

Genomic analysis also helped settle an age-old debate regarding a series of Danish Mesolithic cultures. The successive Maglemose, Kongemose, and Ertebølle hunter-gatherer cultures were present in Denmark from around 10,500 to 5,900 years ago, and archaeologists have distinguished them based on their preferred style of flint blade. The question was whether each culture represented a new population that introduced novel flintknapping styles, or whether an existing population adopted a series of new styles. “We have shown very clearly that during that long period of changing Mesolithic cultures, it’s the same gene pool,” says Allentoft. “It’s not new people coming in with new technologies.”