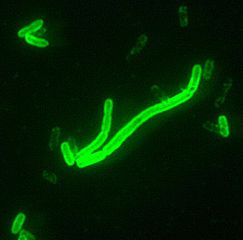

LONDON, ENGLAND—The Black Death of the mid-fourteenth century was not spread by fleas on rats, according to a new study of plague DNA extracted from 25 skeletons unearthed in London last year. Tim Brooks of Public Health England thinks that the Yersinia pestis bacterium must have been transmitted through coughs and sneezes in order for it to have spread through the population so quickly. Archaeologist Don Walker and Jelena Bekvalacs of the Museum of London add that the skeletons show that the people were in poor health when the plague struck—they suffered from rickets, anemia, malnutrition, and bad teeth. A study of the wills registered at the Court of Hustings by archaeologist Barney Sloane estimates that as many as 60 percent of Londoners succumbed to the Black Death. “As an explanation [rat fleas] for the Black Death in its own right, it simply isn’t good enough. It cannot spread fast enough from one household to the next to cause the huge number of cases that we saw during the Black Death epidemics,” Brooks told The Guardian.