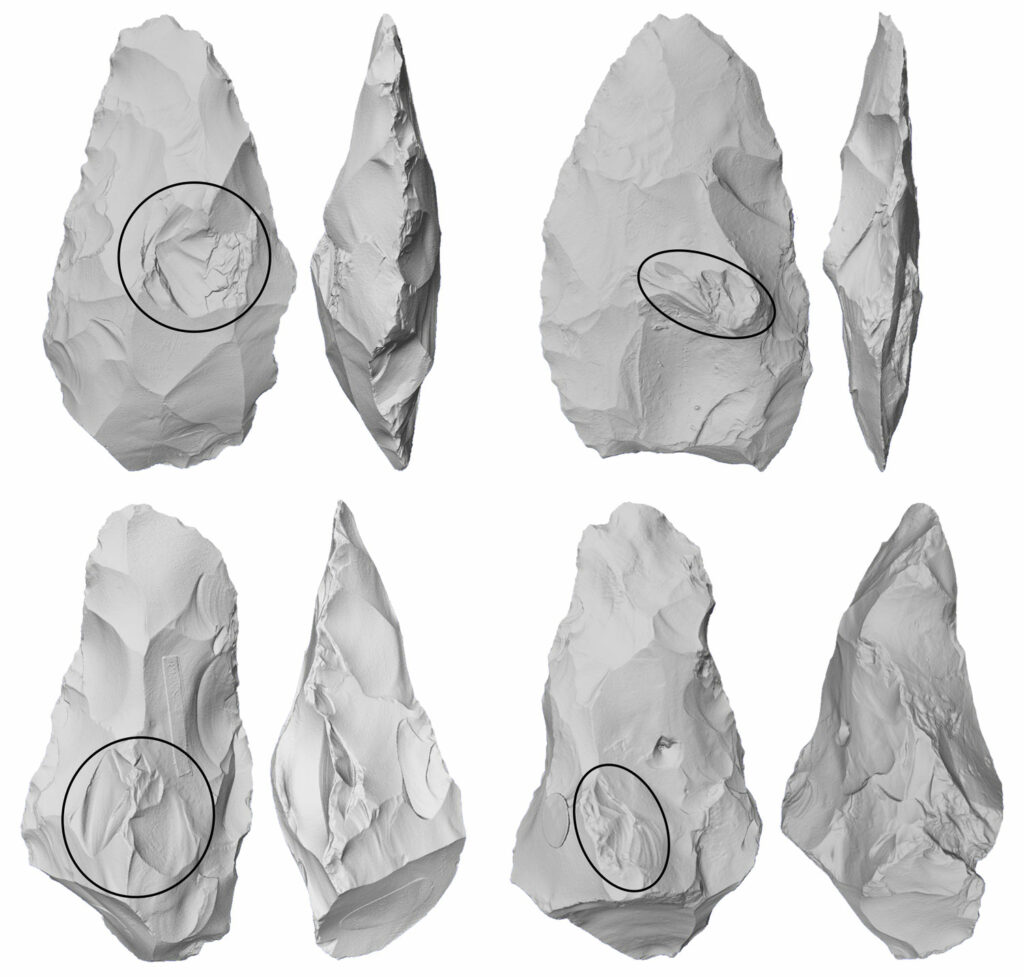

CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA—IFL Science reports that the stone knapping skills of Paleolithic humans living in Britain drastically improved about 500,000 years ago. Handaxes made in Britain more than 560,000 years ago are generally relatively thick and asymmetrical with irregular edges, while handaxes made in Britain after about 480,000 years ago are thin, symmetrical, and regular-edged, according to Ceri Shipton of the Australian National University and her colleagues. The researchers experimented with recreating the tools, and found that the change could be accounted for by learning to rotate a piece of flint continually to produce the optimal angle for striking off a flake of stone. They also determined that the process is aided by using soft hammers made of antler or bone, rather than another stone. In addition, the scientists learned that it is easy to understand how to make symmetrical tools but it is a difficult skill to master, even after 90 hours of training. Previous studies have shown that such advanced knapping training can produce changes in the right ventral premotor cortex of the brain, which is associated with fine motor control and speech. Shipton and her colleagues suggest that the changes observed in prehistoric toolmaking could therefore reflect an evolving physical ability to talk. Read the original scholarly article about this research in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. To read about biological and cultural factors that influenced the development of language, go to "You Say What You Eat."