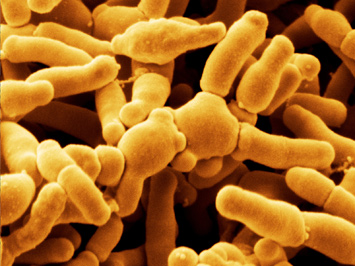

Each of us is home to a vibrant community of gut microbes, the bacteria that live in our digestive systems. Because these bacteria often reflect the diets of their hosts, scientists are examining coprolites—fossilized feces—to learn more about the microbiomes, and lives, of ancient humans.

For instance, the abundance of the bacteria Bifidobacterium breve—commonly found in the stool of recently breastfed children—in a 1,400-year-old sample taken from La Cueva de los Chiquitos Muertos (“The Cave of Dead Children”) in northern Mexico suggests the coprolite had come from a young child. The sample also contained a large quantity of a bacteria called Prevotella, which indicates a diet heavy in carbohydrates but relatively low in proteins.

Cecil M. Lewis, Jr., a molecular anthropologist at the University of Oklahoma, and his team also found Treponema in both ancient samples and modern rural populations. He thinks this implies that both groups have diets heavy in raw, fibrous foods. The microbe, however, does not appear in the stool of urban or Western populations, which might be attributable to more sanitary living conditions. “As we learn more about how well these microbiome profiles predict aspects of the human condition,” says Lewis, “we can use the information to better understand the past.”