Just like the bones of living people with osteoporosis, human remains in the archaeological record can lose bone mass over time. These samples usually require treatment with plastic fillers before they can be moved and studied.

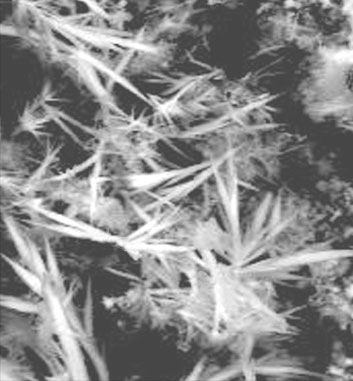

A team of chemists at the University of Florence has devised a novel alternative that uses a chemical reaction to return lost minerals, such as calcium, to fragile old bones. The scientists treated fragments of degraded bone dating from A.D. 1000–1400 with a solution of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles in alcohol. Over several days, the nanoparticles reacted with airborne carbon dioxide and traces of collagen in the bone to form needlelike crystals of aragonite, a hard variant of calcium carbonate that forms naturally in seashells and corals. The crystals left the bones—in this case a saint’s relics from the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome—smoother, whiter, and much stronger.

The method, says study coauthor Luigi Dei, requires further investigation. Unlike the use of plastic fillers to shore up bone, this process is likely irreversible. Once perfected, however, it could be of use wherever archaeologists encounter brittle bones.