Before the California Gold Rush in the late 1840s, there were perhaps 50 native Chinese people in the United States. Just a few decades later, there were more than 100,000, and seemingly every city, town, and remote mining camp in the West had a Chinatown of its own. Chinese immigrants were exotic curiosities, targets of racism and violence—and an essential part of the labor force that settled the West. They left little written history, but dozens upon dozens of archaeological sites and collections are now enriching our understanding of how the first Chinese Americans negotiated life in a strange and sometimes hostile land.

Most of the nineteenth-century Chinese immigrants came from an area the size of Rhode Island—Taishan County, in the southern province of Guangdong, which had suffered the dual indignities of the Opium Wars and the Taiping Rebellion in the 1840s and 1850s. The opening of trade relations between China and the United States, and the discovery of gold in California, spurred the first surge of immigration. In 1852 alone, more than 20,000 Chinese people passed through San Francisco’s Golden Gate. Many found relative safety, comfort, and job opportunities in Chinatowns, which grew first in the cities and then appeared on the frontier as Chinese laborers pursued work in railroad construction, mining, lumber, agriculture, and other industries. Their population in the United States declined following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prohibited new immigration, and would not rebound until the restrictions were lifted 60 years later, starting a second wave of Chinese immigration that has since brought their numbers north of three million.

Archaeological investigation of Chinatowns and Chinese neighborhoods began in the 1970s, with digs at sites such as Ventura, California, and Lovelock, Nevada. There were more in the 1980s and 1990s: Sacramento, San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, San Jose, and others. But most of this early work was cultural resource management—digs related to construction or roadwork—and generated little analysis or scholarship.

Today, Chinese-American archaeology is changing, with new digs, the rediscovery of old collections, and a push to bring researchers together to share findings. Archaeologists and historians have begun working closely with historical societies and descendant communities, and even collaborating with colleagues in southern China. The picture emerging is of a complex, diverse community that held on to some traditions, selectively adopted aspects of Euro-American culture, and tried to make the most of opportunities.

“One of the things that archaeology is doing for all of Chinese America is giving us a greater understanding of what transpired among people who left no or very little written record,” says Sue Fawn Chung, a historian at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who specializes in Chinese-American history.

-

America’s Chinatowns May/June 2014

Women

(Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Arnold Genthe Collection)

(Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Arnold Genthe Collection) -

America’s Chinatowns May/June 2014

Food

(Flickr)

(Flickr) -

America’s Chinatowns May/June 2014

Health

(Courtesy Nevada State Museum, Carson City, Nevada Department of Tourism and Cultural Affairs)

(Courtesy Nevada State Museum, Carson City, Nevada Department of Tourism and Cultural Affairs) -

America’s Chinatowns May/June 2014

Labor

(Courtesy Rebecca Allen, ESA)

(Courtesy Rebecca Allen, ESA) -

America’s Chinatowns May/June 2014

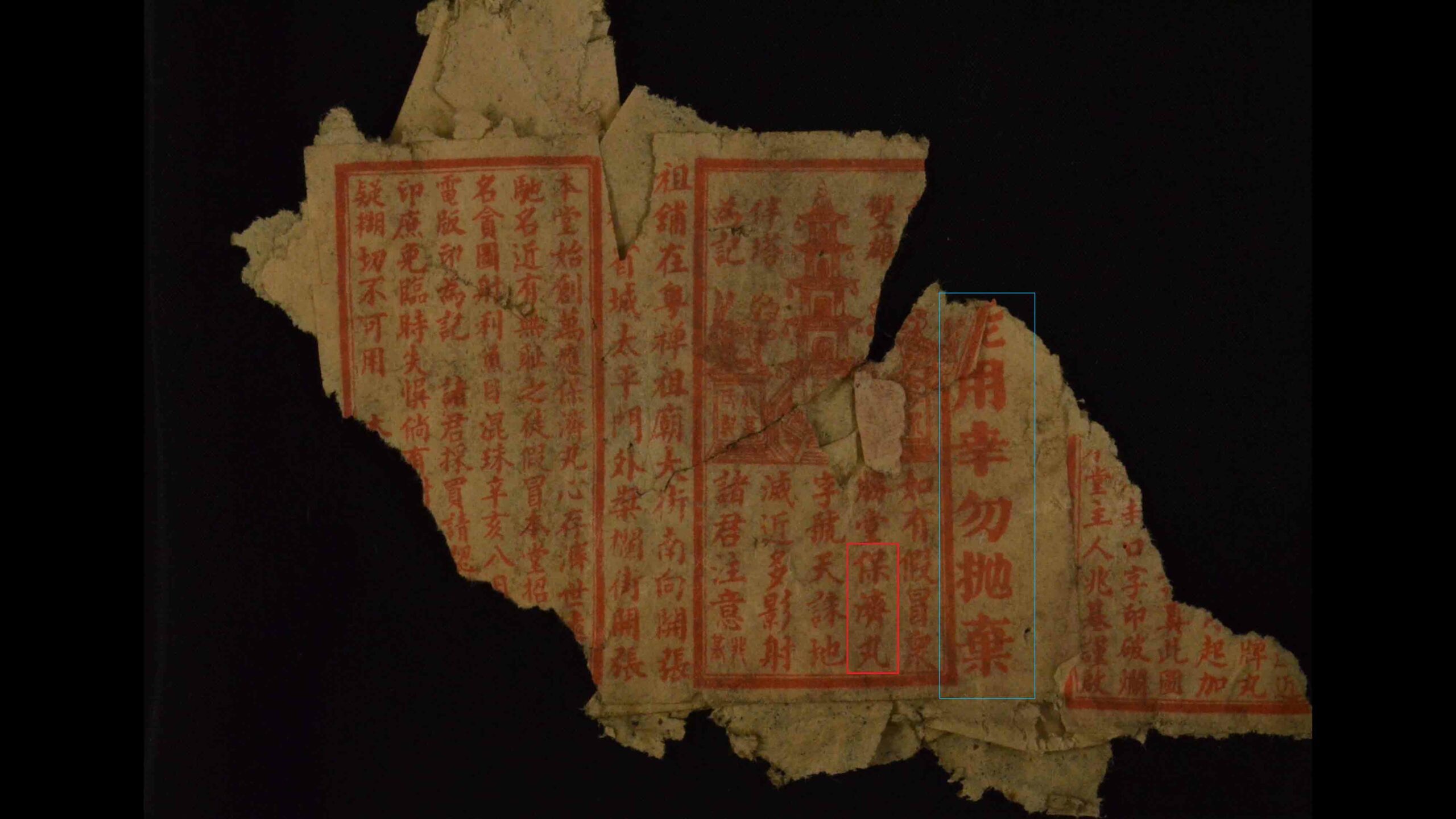

Culture

(Courtesy Market Street Chinatown Archaeological Project)

(Courtesy Market Street Chinatown Archaeological Project)