Each cell in a plant, animal, or person contains millions, or even billions, of DNA base pairs—molecules connected by hydrogen bonds that are the building blocks of DNA. These base pairs collectively make up an organism’s genome, the complete set of its genetic material. The existence of DNA was first discovered more than 150 years ago, and scientists identified its structure in the 1950s. The study of ancient DNA, however, is still in its infancy. Ancient DNA is often fragmented and heavily degraded, making it difficult for researchers to extract and to determine the exact sequence of base pairs in a DNA molecule, a process referred to as sequencing.

In 2010, geneticists successfully mapped an entire Neanderthal genome for the first time. They made the groundbreaking discovery that, even though Neanderthals went extinct about 30,000 years ago, many people today still have genetic variations passed down from these distant human relatives. Fourteen years later, a team of researchers has unveiled a newly sequenced genome belonging to a 200,000-year-old male Denisovan. This archaic human species was itself discovered by recovering DNA from remains in Siberia’s Denisova Cave. Modern humans also share some genetic material with Denisovans. Recent studies of ancient DNA have revealed much more about the human past beyond our genetic connections to extinct human species. In the last decade, scientists have sequenced the genomes of more than 10,000 ancient individuals—some of whom lived more than 400,000 years ago.

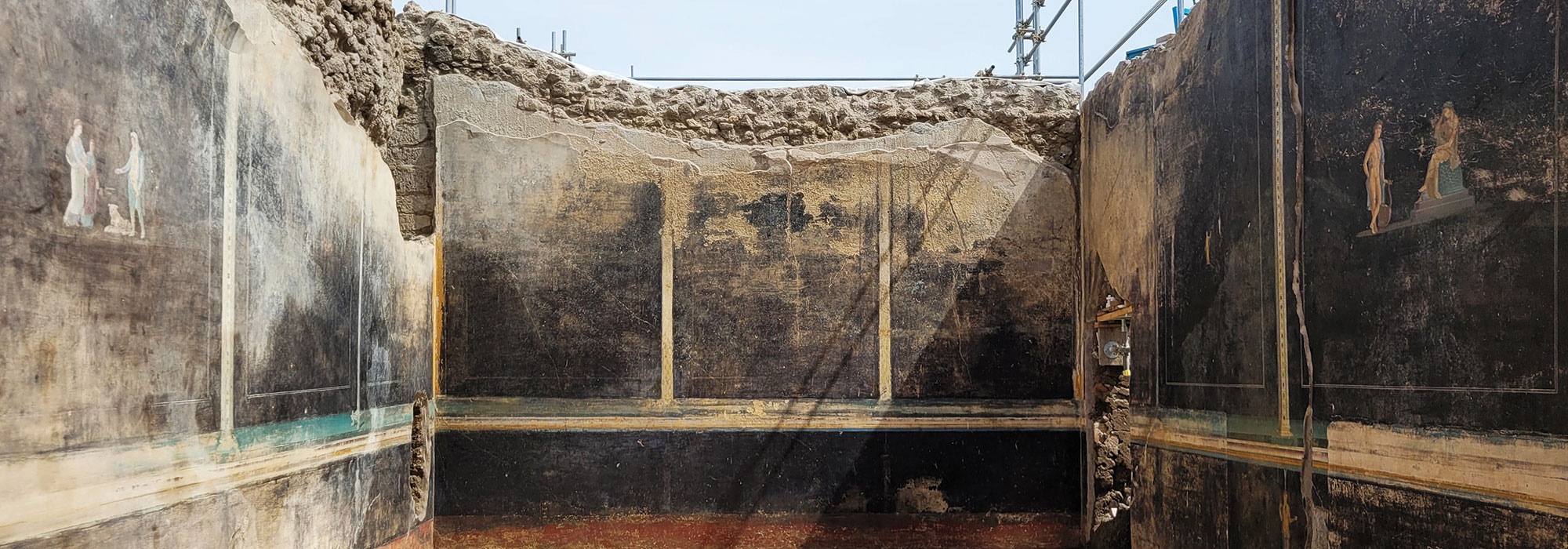

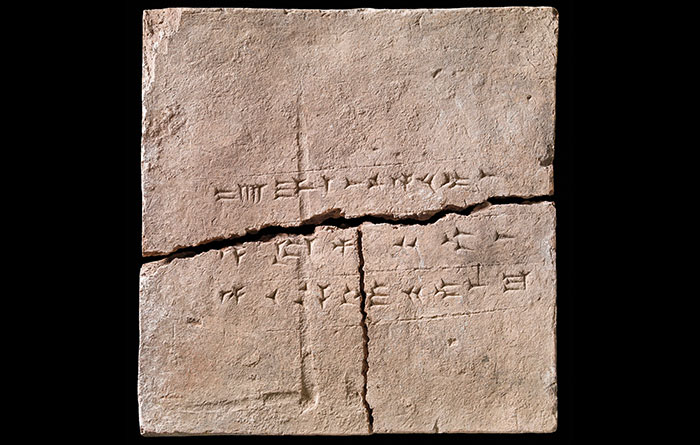

Advances in techniques used to extract and analyze ancient DNA have enabled researchers to recover and study genetic material from an ever-expanding range of archaeological sources, including something as seemingly insignificant as a dark stain in the soil. In order to chart human migration patterns, investigate animal domestication, and reconstruct ancient landscapes, archaeogeneticists continue to develop innovative methods of researching ancient DNA. These new approaches enable them to explore topics ranging from the shifting population of the Roman Empire to the lineage of an extinct dog treasured by the Indigenous Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest to the specific plants that grew in an Assyrian king’s garden.

-

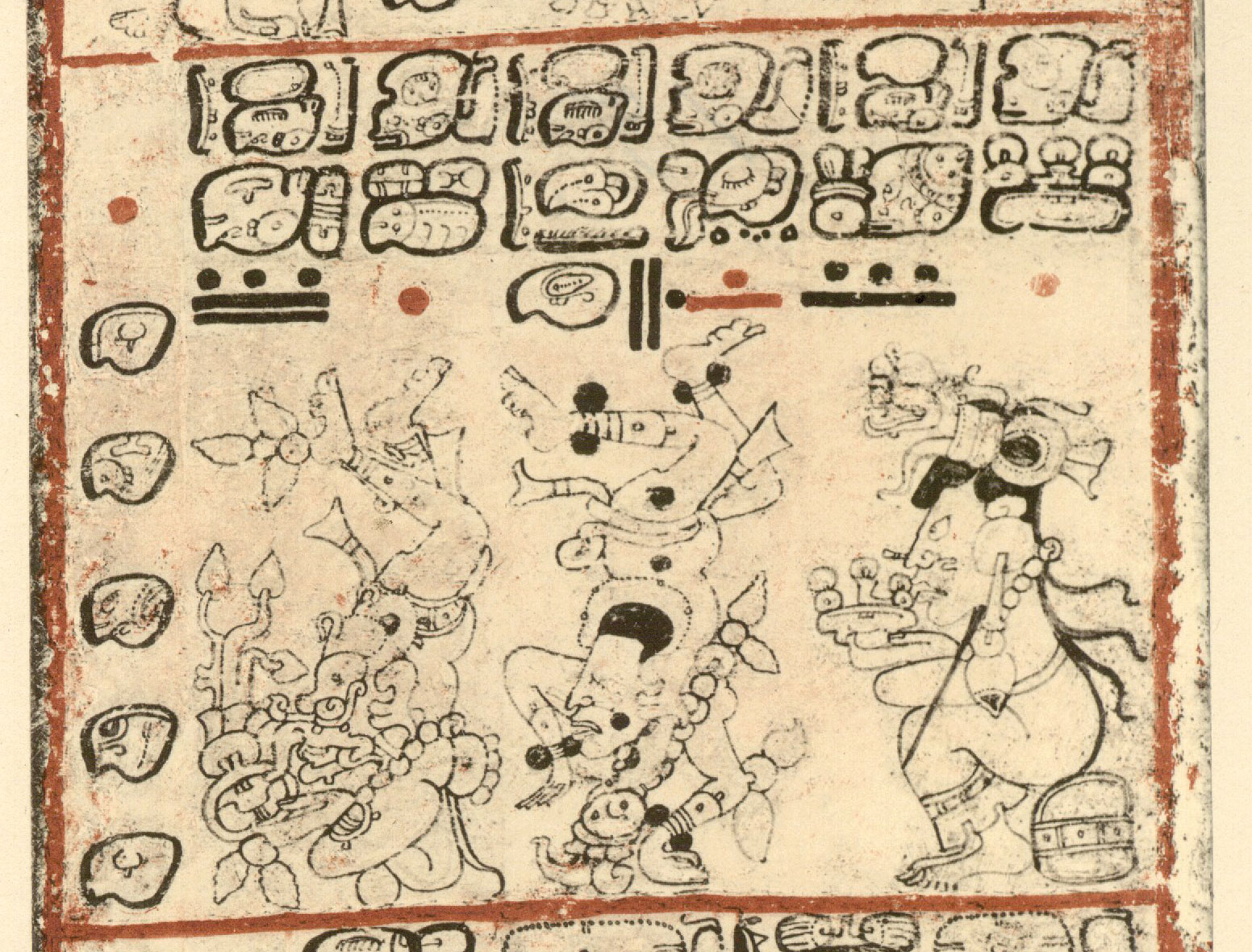

SLUB Dresden, Mscr.Dresd.R.310, http://digital.slub-dresden. de/id280742827 (Public Domain Mark 1.0)

SLUB Dresden, Mscr.Dresd.R.310, http://digital.slub-dresden. de/id280742827 (Public Domain Mark 1.0) -

AdobeStock/ Kavalenkava

AdobeStock/ Kavalenkava -

Ancient DNA Revolution September/October 2024

Wild and Woolly Ancestors

Washington State and British Columbia, United States and Canada

Illustration Karen Carr

Illustration Karen Carr -

Svetlana Sharapova

Svetlana Sharapova -

AdobeStock/lucaar

AdobeStock/lucaar -

Danish National Museum & Anders Fischer/A. Fischer, et al, J. Archaeol. Sci.:Rep Vol 39 103102 (2021)

Danish National Museum & Anders Fischer/A. Fischer, et al, J. Archaeol. Sci.:Rep Vol 39 103102 (2021) -

National Museum of Denmark (museum number 13854)/Photo: Arnold Mikkelsen and Jens Lauridsen

National Museum of Denmark (museum number 13854)/Photo: Arnold Mikkelsen and Jens Lauridsen -

PA Media Pte Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo

PA Media Pte Ltd/Alamy Stock Photo -

Library of Congress

Library of Congress