An enormous bug-eyed dragon fends off an attack by a pair of lions. The toothy maw of a killer whale erupts from the earth across the way from an immense lumbering tortoise that carries a female figure, perhaps the goddess Fame, on its back. A huge siren with two tails sits opposite an equally large winged harpy with a serpent’s tail and a lion’s claws. These fantastical sculptures are among dozens of such creations lining the paths that wind through a forested ravine below Bomarzo, a medieval town in the Lazio region of Italy. Known as the Sacro Bosco, or the Sacred Wood, this is among the most unusual designed landscapes of the Italian Renaissance. “Upon first visiting the Sacro Bosco, I was completely overwhelmed by the scale of the statuary and how interestingly it was woven into the landscape,” says John Garton, an art historian at Clark University. “You would literally come out of vegetation and suddenly there would be this more than two-story-tall monument carved out of native stone. I’ve since realized it’s meant to be jarring. It’s intended to be this site of spectacular revelations where monsters come to life and things that have only been known through literature and books jump out at you.”

The Sacro Bosco was the brainchild of Pier Francesco Orsini, who inherited the duchy of Bomarzo in 1542 and began work on the sculpture park around a decade later. Orsini and others who visited the grounds in the sixteenth century left only a few written references to the wood. Scholars have proposed a variety of ways to interpret the park, but there is little agreement as to what message—if any—Orsini intended to convey through his creation. “We have so little information about both the design and the experience of the site when it was laid out,” says art historian Luke Morgan of Monash University. “There are very few documents from the period. No building records exist, for example.” Even the most basic element of this experience—whether guests were meant to follow a particular route when navigating the park’s walkways, and what that route might have been—is unknown. In the latest attempt to understand Orsini’s vision, Garton, Morgan, and colleagues at the University of Padua and the University of Brescia have launched the Digital Bomarzo Project. They are employing modern imaging technology to thoroughly document the site and better identify what a visitor roaming the Sacro Bosco in the years after it was constructed might have encountered there. In particular, they have made tantalizing new discoveries about how now-defunct fountains would have added an additional sensory dimension to a journey through the unique park.

Typical gardens of the Italian Renaissance were situated directly alongside villas and laid out in an orderly, geometric manner. They are thought to have embodied the concept of the locus amoenus, or “pleasant place,” referenced by classical authors such as Homer and Virgil and by Renaissance thinkers. “According to the conventional perspective, these were places apart that embodied an idealized notion of nature,” says Morgan. “You can read this through the statuary, the architecture, and the experience of the garden.” In some cases, boschetti, or “small woods,” were designed to accompany gardens.

The Sacro Bosco was a different sort of beast. It was nearly a fifth of a mile from the grand residence of the garden’s creator, the Palazzo Orsini. A swath of fields separated the palazzo from the wood—which fit nobody’s definition of a pleasant place. Not far from the tortoise, a pair of giants engage in a brutal wrestling match, with one calmly ripping the other limb from limb, eliciting an anguished scream. “If Renaissance gardens are idealized places apart, why do these monstrous figures appear, why do images of violence appear?” wonders Morgan. “There’s no way to interpret the fighting giants but as an image of extreme physical violence in a designed landscape.”

For Morgan, one way of understanding the Sacro Bosco is as a statuary version of grottesche, or “grotesque,” artistry. This style became wildly popular in Italy after the late fifteenth-century discovery of the Domus Aurea, the ultra-lavish residence of the emperor Nero (reigned a.d. 54–68) in Rome. (See “Golden House of an Emperor.”) The sprawling estate’s walls were covered with paintings, some featuring bizarre or mythical creatures in strange combinations. These works inspired Renaissance artists, who avidly sought out models from the distant past to fuel their creativity. During the first explorations of the Domus Aurea, the ruins were thought to be grotte, or “caves,” which is the source of the name given to this artistic style. “If you go into almost any palazzo or villa, or even church, of that period, you’ll find grottesche imagery—hybrid fanciful figures in which women become fish, men transform into plants, and buildings are supported on slender stalks,” says Morgan. The Sacro Bosco is replete with such depictions, from the massive siren and harpy to the winged horse Pegasus and the three-headed dog Cerberus, who guards the gates to the underworld. It’s little surprise that the Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, known for his hallucinatory imagery, was enchanted by the site when he visited in 1948.

The raw material used to create the Sacro Bosco’s sculptures is another way its design draws inspiration from the past. Many of the park’s enormous works were carved in situ from peperino, a type of volcanic rock found there. The apparently haphazard layout of the sculptures was likely dictated by the location of rocks with good sculpting potential, not a preconceived plan. “Orsini seems to have come to the site and seen a very large boulder and decided to create a colossal figurative group out of it,” says Morgan. “Somewhere else, he saw a smaller boulder, so he had his sculptors carve something else out of it.” This practice of sculpting from “living rock” harks back to the Etruscans, who flourished in the area from around 900 to 300 b.c., predating the Romans. The area surrounding the Sacro Bosco is filled with Etruscan ruins, including tombs carved out of the local rock. One of the sculptures in the park is a faux Etruscan tomb facade, intentionally collapsed in a manner intended to mimic these ancient remnants. “The Sacro Bosco is a response to Etruscan antiquity rather than Greco-Roman antiquity, which is much more familiar to us,” says Morgan. “There’s a prestige in Renaissance Italy associated with antiquity in general, and the Sacro Bosco and Orsini can lay claim to a much more ancient tradition than is found in other parts of the peninsula.”

The colossal size of many of the Sacro Bosco’s sculptures was an additional way in which their creators, like others in the Renaissance, took their cue from the past. Renaissance artists learned, for example, of the Colossus of Rhodes from the first-century a.d. Roman author Pliny the Elder. The Colossus was a 100-foot-tall bronze statue representing the Greek sun god Helios that once stood at the entrance to the port of the Greek island of Rhodes. Indeed, the word “colossal” derives from this and other gargantuan works of art sculpted by the Greeks and Romans. An inscription near the fighting giants in the Sacro Bosco claims a kinship with this famous statue, which was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. “Just as Rhodes was filled with pride about its Colossus,” the inscription reads, “so my wood is renowned for the same reason; and, unable to do more, I do what I can.”

Orsini was a learned man who possessed a sophisticated knowledge of the literary currents of his time. Thus, scholars have looked to Italian literature for possible sources of inspiration for the Sacro Bosco’s inscrutable sculptures. A 1499 romance called Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Francesco Colonna, in which the main character wanders lost in the woods before emerging into an ancient dreamscape, may have influenced the design of the park as a whole. A likely source for the fighting giants is Orlando Furioso, a 1532 epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto, in which the protagonist, driven mad by unrequited love, tears a woodsman in two. “The woods are a kind of fearful place,” says Morgan. “They’re dark and conceal unknown terrors, and all of that is present in the Sacro Bosco.”

The park’s most explicit, albeit cryptic, literary allusion was embedded in an inscription on its most fearsome sculpture: the Hell Mouth. Today, this roaring mask’s upper lip bears the words Ogni pensiero vola, or “Every thought flies.” However, some of the letters were painted, not carved into the rock, an addition that was likely made in the mid-twentieth century. Peperino is a soft, porous stone that wears away easily. A 1604 drawing by the artist Giovanni Guerra establishes that the inscription was significantly longer at the time and thus must have eroded over the centuries. The drawing shows that the inscription originally read Lasciate ogni pensiero voi ch’entrate, or “Abandon all thought, you who enter.” This is a play on the phrase above the entrance to Hell in the late medieval Italian poet Dante’s Inferno: “Abandon all hope, you who enter.”

Emblematic of Orsini’s eccentric worldview, the Hell Mouth was designed to serve as an alfresco dining room, with its tongue forming the table. Descriptions and drawings from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries show that revelers gathered to feast inside the ghoulish mask while musicians played and torchlight leapt from its mouth and eyes. This incongruous party spot might help explain the inscription’s meaning. “Maybe you are being encouraged to enjoy yourself, not to think too hard about the fact that you’re entering Hell to have a pleasant meal outdoors in a garden,” says Morgan. “One way to understand the phrase is as an exhortation to abandon yourself to physical pleasures.”

The possibility that the Sacro Bosco can be interpreted as an expression of Orsini’s personal philosophy or biography has long tantalized scholars. The duke married Giulia Farnese, a great-niece of Pope Paul III, soon after inheriting Bomarzo in 1542. A condottiero, or military leader, Orsini was taken prisoner in the early 1550s while fighting in France. Giulia died in 1560, not long after Orsini was released and returned to Bomarzo. Much of the Sacro Bosco was completed after her death, leading scholars to speculate that the park, several of whose sculptures conjure the underworld, was a reflection of Orsini’s grief. A small temple at the wood’s highest elevation has a ceiling decorated with roses, which are associated with the Orsinis, and lilies, the heraldic symbol of the Farneses. “This may be a memorial to Orsini’s deceased wife,” says Morgan. “Once you get to that spot, you emerge into a clearing where there is this classicizing temple, and you feel like you have left the monsters behind.”

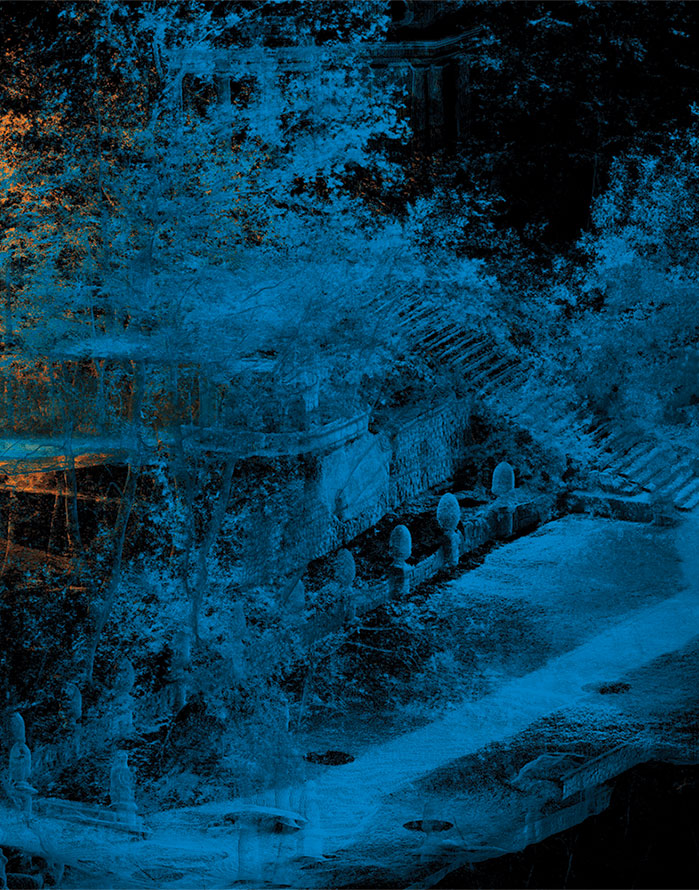

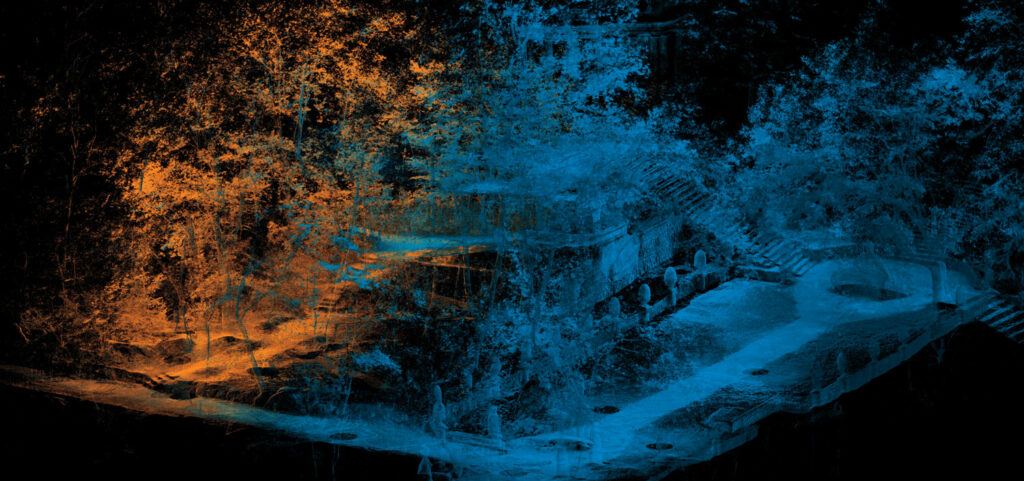

To preserve the fanciful details of the garden’s sculptures for scholars and so that people can enjoy the park in the future, the Digital Bomarzo Project is using imaging techniques such as lidar, photogrammetry, and digital scanning of each sculpture to create a 3D model of the entire site. The region is highly prone to earthquakes—in fact, one of the Sacro Bosco’s works, a house leaning at a precipitous angle, as if uprooted from its foundations, may be a sly reference to the area’s seismic activity. “In the future, there could be an earthquake that would significantly alter what’s on the ground,” says Garton. “We are keen to make sure our scanning is as precise as we can make it. We will have an archive of all the monuments down to their last centimeter in a way that could allow for reconstruction should they be damaged.”

A now-hidden feature of the Sacro Bosco are the fountains included in its original design. By looking underground, the team has learned a significant amount about the role waterworks originally played in the park. Some elements, such as the sculpture of Pegasus, clearly once functioned as fountains. The researchers have used ground-penetrating radar to identify voids that appear to hold water pipes near a number of other sculptures, including a boat-shaped tub adorned with dolphins. “We know from a sixteenth-century source that the Sacro Bosco’s waterworks were highly regarded,” says Garton. “Yet, when you visit today, you would have no clue that there were once gurgling fountains that would have produced audible as well as visual splendor.”

Among the enduring mysteries of the Sacro Bosco is the identity of the architect and sculptors Orsini employed to execute his vision—information he neglected to include in the few surviving documents relating to the site. “One of the maddening things about working on the Sacro Bosco is how little historic written evidence there is,” says Garton. “We have to re-create quite a bit from a close look at what is on the ground. That’s all there is to go by.” The researchers hope to identify Orsini’s artistic partners by comparing their digital scans of the park’s features with those of other Renaissance sculptures and structures.

One question researchers do not anticipate being able to answer is what itinerary early visitors would have taken through the Sacro Bosco. There are multiple ways to explore the wood, and there may once have been multiple entrances. “The experience is a disorientating one, and it seems to me that there was no predetermined route,” says Morgan. “Strange figures loom out of the undergrowth and the darkness. You feel lost in the dark wood like Dante in the Divine Comedy. But then you make your way and make your own choices about the route that you take through it.” Just as there is no single pathway through the wood, there is no single way of interpreting it, no single text that can unlock its secrets. “The experience of the Sacro Bosco is more like flipping between the pages of a whole range of texts that don’t necessarily cohere into a single linear narrative,” says Morgan. “This is all part of why it has fascinated people for so long.”

Slideshow: Garden of the Grotesque

The Sacro Bosco, or Sacred Wood, was the creation of Pier Francesco Orsini, the duke of Bomarzo, who lived from 1523 to 1583. Orsini left little written record of his intentions in the design of the park and its several dozen highly imaginative sculptures, but his inspirations appear to have included mythology, literature, the ancient history of the Bomarzo region, and even his own biography. However scholars choose to interpret Orsini’s eccentric concoction, all agree that it is one of the most unusual and beguiling spaces of the Italian Renaissance.