Greece’s unique shape makes it one of the most recognizable countries on a map of Europe. The mountainous peninsula juts into the Mediterranean Sea and is divided into two distinctive parts. The southern section, the Peloponnese, is attached to mainland Greece by a narrow strip of land, the Isthmus of Corinth. Measuring just four miles wide in places, the isthmus separates the Saronic Gulf to the east from the Gulf of Corinth to the west. Over the course of Greece’s history, this land bridge has been a vital artery for trade, travel, military transport, and communication.

Throughout that time, it has also been a place where people have settled, with no location more renowned than Corinth itself, one of the most powerful and influential city-states of ancient Greece. Countless archaeological sites dot the landscape, spanning thousands of years and bridging multiple eras—Neolithic, Mycenaean, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman. For centuries, antiquarians, travelers, and archaeologists have flocked to the isthmus and to the Corinthia, the area that includes Corinth and its immediate surroundings, making this one of the most intensively studied regions of Greece. Very little has escaped archaeologists’ attention, save, perhaps, for one place—a site called Washingtonia.

Washingtonia was a short-lived colony established for refugees whose lives had been torn apart during the Greek War of Independence, which lasted from 1821 to 1829. It was an experiment in nineteenth-century utopianism born in the first years of the modern Greek state. The mission was led by an American, Samuel Gridley Howe, whose own country had only recently won its independence. Guided by optimism, and as a nod to his homeland, Howe named his fledgling colony Washingtonia, after the man who had led the United States to freedom from the British. He hoped that the settlement might become the capital of the new nation. But almost as quickly as it appeared, Washingtonia was gone. In a matter of decades, there was little visible evidence that it had ever existed. The colony survived only as an obscure footnote in history books and in the fading memory of local residents.

To archaeologists a century and a half later, Washingtonia seemed almost fictitious. Archaeologist David Pettegrew of Messiah University first came across the settlement’s name while working with the Eastern Korinthia Archaeological Survey in the 1990s. In the process of conducting an exhaustive survey of archaeological sites in the Corinthia, the team came across a brief reference to Washingtonia in a book written by Boston University archaeologist James Wiseman in the 1970s. “It became this funny kind of thing,” says Pettegrew. “‘Where is this Washingtonia, and what is a Washingtonia doing on the isthmus?’ We were interested in locating it, but we ran into problems because there were just too many assumptions to make.”

Nearly three decades later, Pettegrew teamed up with Franklin & Marshall College archaeologist Kostis Kourelis, Harrisburg University geospatial specialist Albert Sarvis, and University of Missouri–St. Louis historian Nikos Poulopoulos to test some of their assumptions regarding the colony’s location. Relying on Howe’s journals and letters, nineteenth-century maps, and modern technology, the team learned not only why a Washingtonia was on the Isthmus of Corinth, but also managed to find it.

Later in his life, Howe would become a fervent abolitionist and attain renown as an educator of the blind. In 1825, just 24 years old and fresh out of Harvard Medical School, the idealistic Howe traveled to Greece, where he volunteered to serve as a doctor in the Greek Navy to help in the struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire. “There’s romanticism in going to Greece and joining a bunch of Europeans who are changing the world,” says Kourelis. But Howe was taken aback by the situation he encountered. War had ravaged the countryside, and he saw firsthand the resulting humanitarian crisis. Tens of thousands of Greeks had been displaced from their homes and were in desperate need of aid. Howe soon became involved in a number of philanthropic projects. During a brief trip back to the United States, he raised $60,000—the equivalent of $2 million today. Howe realized, though, that simply distributing assistance to the poor was not enough, as this only provided a temporary fix to a much deeper, more enduring problem. A better solution would be to help families secure their own futures. “Howe thought, ‘We have to figure out a way not just to give out money or food, we need to create a situation so that these people can eventually sustain themselves,’” says Poulopoulos.

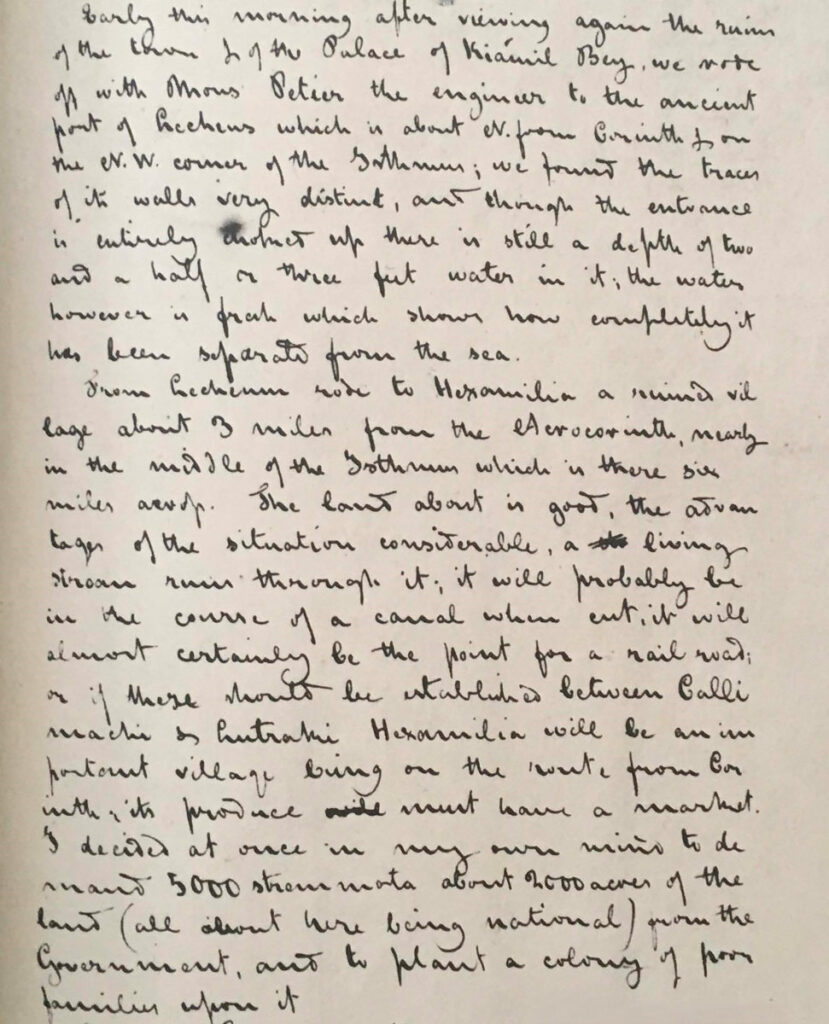

Howe resolved to establish a colony that could support itself in the short term and prosper financially in the future. After discussions with Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first elected governor of independent Greece, Howe was granted 2,000 acres on the Isthmus of Corinth near an abandoned village called Ano Examilia. The Corinthia had suffered particularly badly during the war and was in dire need of rebuilding and reinvestment. It had arable land and fresh water, proximity to important trade routes, and access to a nearby port at Kenchreai. Howe also had other reasons to favor the locale, as he suspected a planned canal through the isthmus might pass directly by his new colony, dramatically boosting its prospects. There was even talk that, given the isthmus’ strategic location, the capital of the Greek state might be established at Corinth. “It was the best place that you could claim at this point in time,” says Poulopoulos.

Howe selected 26 displaced families from around Greece as Washingtonia’s inaugural residents. In the first few months, these colonists, along with a local workforce, began rebuilding demolished houses belonging to a ruined Ottoman village on the site. The workers cleared the land and planted vineyards and olive trees, crops such as wheat, corn, and barley, and various other fruits and vegetables. Cattle were purchased, a school was opened, port facilities were built, and the foundations of a hospital were laid. There was even a pharmacy to supply much-needed medicine. “It’s pretty amazing,” says Poulopoulos. “I don’t think there were too many places in Greece that had a drugstore at that point.”

Howe surveyed Washingtonia’s progress from his home, the colony’s de facto headquarters. The land he had been given for his settlement had previously belonged to Kiamil Bey, the deposed Ottoman governor of the Corinthia. The governor’s country residence had been demolished in the war, and Howe rebuilt it and transformed it into his own accommodations. It offered sweeping views across the isthmus and was an ideal place from which to monitor Washingtonia’s daily happenings. It’s hard to imagine that Howe wasn’t thoroughly encouraged by what he saw. The colony was growing as more displaced families moved in. Although records are sparse, its population may have reached 225 by the end of its first year. Washingtonia appeared to be well on its way to the success that Howe had envisioned.

Despite its auspicious start, things unraveled in the ensuing years. Crops failed and cattle became diseased. Washingtonia and its inhabitants were frequently attacked by bands of brigands during a period of civil strife that followed Greek independence. Many of the settlement’s new and reconstructed buildings were torn down. Howe himself departed Greece in 1830 due to health issues and a series of personal challenges. In addition, his relationship with Kapodistrias had soured, and Howe seemed to have become somewhat disillusioned. One of the last surviving records of the colony is an 1834 tax document. It lists some of Washingtonia’s existing infrastructure, but also notes that much of the colony had been destroyed in the recent turmoil. A number of the original colonists left, with some joining neighboring villages. Gradually, even the name Washingtonia faded from use. Its buildings were swallowed by the landscape or buried beneath newer structures. “Americans forgot it,” says Pettegrew. “Even archaeologists forgot it.”

Well into the twenty-first century, Washingtonia’s precise whereabouts remained a mystery. A few archaeologists working in the Corinthia had a vague notion that it had existed, but it garnered little attention. “They knew the idea of it,” says Kourelis. “But they were focused so much on Greek and Roman times that they never bothered to devote any fieldwork to identifying it.” In 2016, Kourelis, Pettegrew, and Sarvis set out to locate the colony once and for all using a multifaceted approach. They pored over Howe’s diary and personal letters, Greek government documents, historical maps, and eyewitness accounts from nineteenth-century travelers. They also relied on modern methods such as geographic information system (GIS) software, satellite photography, and drone surveys.

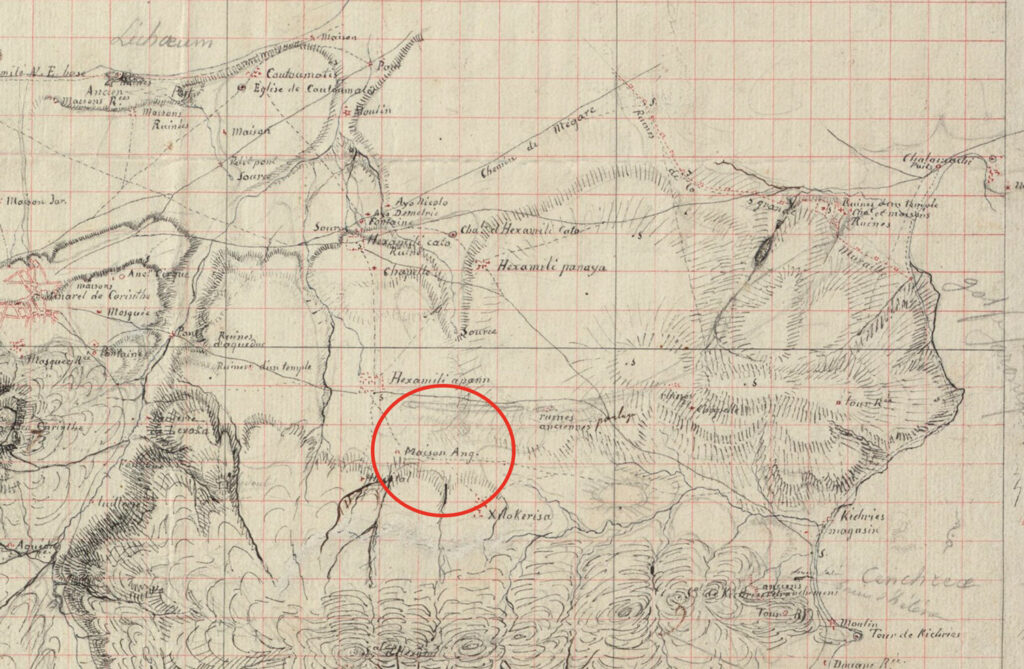

One point of reference the archaeologists could start from was the knowledge that Washingtonia had been located near Ano, or Upper, Examilia, which is sometimes written Hexamilia. Today, there is a modern village called Examilia near Corinth. In the past, those few archaeologists who gave Washingtonia any thought simply assumed it was located somewhere within or beneath that village. But no trace of the colony had ever been identified there. Tracking down the site of Washingtonia, or even the Ottoman-era village of Ano Examilia, proved a challenge. The word examilia in Greek translates to “six miles,” which is roughly the width of the isthmus near Corinth. Consequently, there are several features in the vicinity that include “examilia” in their names. One nineteenth-century map the team examined has at least three villages close to one another with some version of the name: Hexamili Apano, Hexamili Cato, and Hexamili.

The team ran into another problem when they realized that the topography of the isthmus has slightly changed since the time of Washingtonia’s founding. Over the past 200 years, the area has been struck by a series of devastating earthquakes. This has sometimes caused towns and villages to disappear or even to relocate, taking their old names with them. Even Corinth itself, after being flattened by an earthquake in 1858, was refounded as New Corinth a few miles away. “What we have discovered is that settlements on the isthmus in the late Ottoman and early modern period flicker on and off,” says Pettegrew. “They move around a lot.” It was not a certainty that modern Examilia was even the same village as Washingtonia-era Ano Examilia.

The team did have Howe’s description of the site, which he had recorded in his journal. Howe reports that his house was built on an outcropping of land at the base of a small mountain, and that from his balcony, he could see the Saronic Gulf and the Gulf of Corinth on either side of the isthmus. Archaeologists knew that there couldn’t be many places in the Corinthia that matched this description, so they set out across the isthmus, aided by GIS, to try to pinpoint potential locations where Howe’s residence could have been situated. “I started playing around with digital elevation models,” says Sarvis. “Where can you actually see both bodies of water from approximately ten to fifteen feet off the ground, the height of the second-floor balcony that Howe described?”

This helped narrow the search area, but a major breakthrough came when the team was approached by Poulopoulos, who was working on a different project focused on the history of the Greek Revolution. Poulopoulos had a collection of maps in his possession—and he believed that one particular map would be of great help to the Washingtonia quest. He had not appreciated the map’s potential value at first, as his gaze had been fixed on an entirely different portion of the document. “Initially, because my project had nothing to do with Washingtonia, I never paid attention to it,” Poulopoulos says. “At some point, I turned back to it and I kept questioning why certain things were on it. I eventually connected it with Howe and his colony.”

Members of the Washingtonia team had examined a slew of historical maps, but had found it difficult to precisely correlate nineteenth-century places with features in the modern landscape. Poulopoulos’ map was different. It had been drawn by French geographer Pierre Peytier, who, between 1829 and 1831, was commissioned to create the first comprehensive scientific map of the Peloponnese. This official map, which was published in 1832, is well known to archaeologists, including Pettegrew and Kourelis. The map that Poulopoulos had, however, was not part of that publication. It was a draft that Peytier had made prior to the final version. It contained his handwritten notes and a meticulous sketch of the isthmus that included details such as mosques, chapels, towers, and fountains not found on any other map. “It really was the key that unlocked it all,” Pettegrew says. The team believed that Peytier’s draft map could be trusted because he had known Howe personally—he had even visited the site of Washingtonia. By digitally layering Peytier’s map on top of modern maps and aerial images, a process called georeferencing, they soon identified specific Ottoman-era monuments, such as a small mudbrick chapel and a masonry tower at Kenchreai. Finally, they could orient themselves and their search in a way that hadn’t previously been possible.

There was one handwritten notation on Peytier’s map that the team found particularly curious. It read “Maison Ang.” and marked a spot between the villages of Hexamili Apano and Xylokeriza. The archaeologists deduced that the notation stood for maison anglais, or “English house” in French, but didn’t know exactly what that referred to. They reasoned that it must have been noteworthy to get its own label. In 2023, thanks to Peytier’s map and Sarvis’ ability to georeference it using GIS, the team located the exact spot of the maison anglais at a place known today as Botizia ridge. When Pettegrew, Kourelis, and Sarvis visited the site and conducted initial archaeological reconnaissance, they discovered the ruins of a nineteenth-century building, as well as contemporaneous artifacts such as bricks, tiles, ceramics, and glass. As they stood atop the ridge and took in the vista across the isthmus, they saw both gulfs and realized they were looking from the very same vantage point that Howe had described in his journal. They were, in fact, standing amid the ruins of Howe’s residence—the first tangible evidence of Washingtonia that had ever been found.

Locating Howe’s residence has made it easier for the team to begin to identify other aspects of the colony’s infrastructure. They believe they have discovered remnants of the original colonists’ houses, which were laid out in three long parallel rows. Some of these single-story structures still stand within the modern village of Examilia and can be seen behind or attached to multistory residences built decades later. One of the most significant realizations that the archaeologists have arrived at over the past few years is that the remnants of Washingtonia cannot be found at a single site lost beneath the modern landscape. Rather, the colony consisted of many different elements that were built across the isthmus and down to the coast of the Saronic Gulf. Most of these elements have disappeared, or are yet to be identified. “It’s an extended topography that includes all of these two thousand acres,” says Poulopoulos. “It’s not a specific building, it’s not a specific site. It’s this whole project and it has many aspects, all of which had to be successful individually.”

Although Howe’s colony never achieved the lofty goals he had dreamed of, Washingtonia did provide a vital place of refuge for people during dark times, even if only briefly. It gave hope and a new start in life to families who had lost everything. When Howe returned to visit the site of Washingtonia in 1844, local villagers still recognized him and showered him with appreciation for all he had done for them. According to Kourelis, Washingtonia’s disappearance can actually be viewed as a sign of its ultimate achievement. “The success of a refugee colony is exactly when you don’t hear about it anymore and it disappears, because there is integration,” says Kourelis. “The objective of humanitarianism is for it to stop. If Washingtonia remained as an American colony, it would have been extremely problematic.”

Howe would continue his humanitarian work for the rest of his life. He dedicated his medical career to treating disabled people, founding the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, whose most famous pupil was Helen Keller. He was a staunch opponent of slavery and was rumored to have been one of the financial backers of John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry. Howe married social activist, suffragette, and author Julia Ward Howe, who is best known for penning the words to the Civil War anthem the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” There are stories from the 1960s and 1970s of American archaeology students in Corinth routinely singing that very same song, just a few miles removed from the former colony—an echo of the distant connection to Howe, Washingtonia, and a little-known chapter of both Greek and American history.