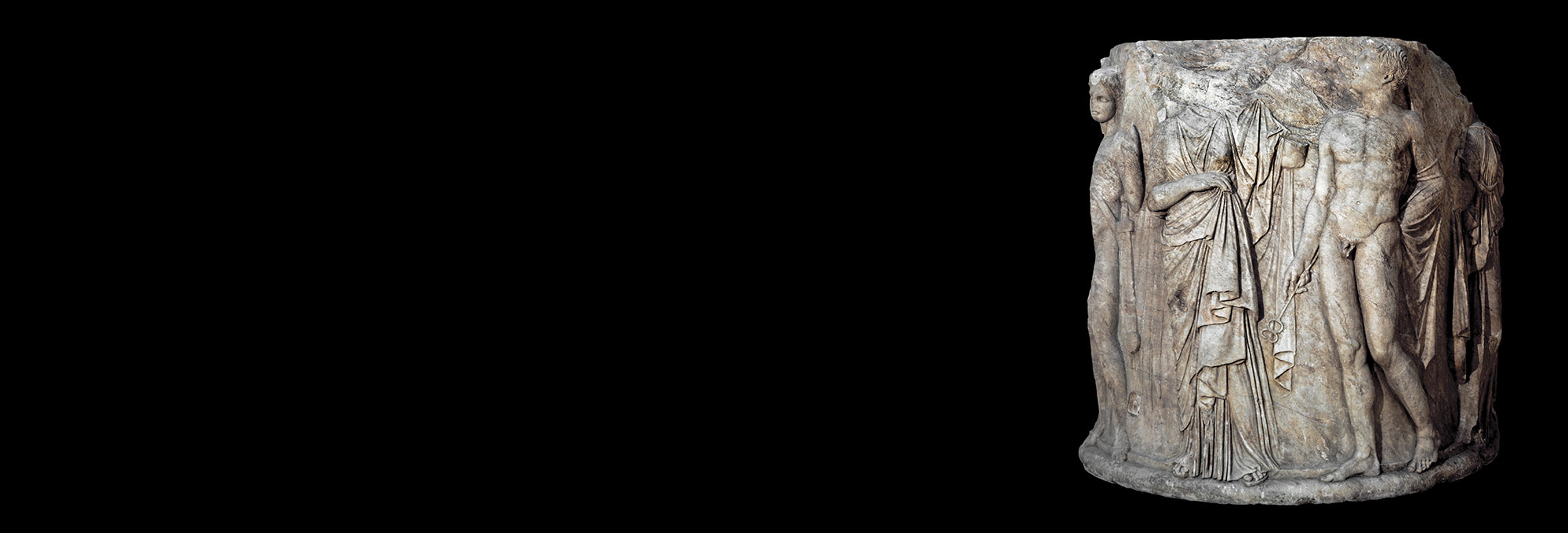

In 1863, as part of an all-out race by European museum directors to acquire the most spectacular remnants of the classical world, the British Museum began to sponsor excavations in Ephesus. The museum’s archaeologists had previously found pieces of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus in 1856—another wonder would certainly be a very large feather in their cap. Several ancient sources mention the Temple of Artemis, including the first-century a.d. Roman historian Pliny the Elder, who names the edifice’s fourth-century b.c. architect and marvels at the engineering feats required to raise an all-marble building 450 feet long and nearly 225 feet wide. Pliny also remarks on the temple’s 60-foot-high columns, 36 of which had bases covered with carved reliefs. Just two centuries later, the building he describes was gone. In 1869, it had been nearly two millennia since anyone had seen the Temple of Artemis. That year, the British Museum team, led by engineer turned amateur archaeologist John Turtle Wood, discovered several of the temple’s sculptures and architectural elements, including one of its famed decorated column bases.

Since then, only the sanctuary wall, the foundation of the temple, and its enormous altar have been unearthed. Without anything else in situ it has been difficult for archaeologists to fathom what the structure looked like. Using Greek and Roman writers’ descriptions, ancient coins, and studies of similar temples, a team led by engineer Ahmet Denker of Istanbul Bilgi University has created a 3D model of the temple as it may have looked in the fourth century b.c. What they have reimagined is a structure remarkable not only for its size but also for its odd number of columns. In addition to the 21 columns along each side of the temple, there were eight columns across the front and nine across the back. The larger spaces between the columns on the facade allowed visitors to be awed by the huge statue of Artemis inside. Other unique features of the temple include the carved column bases; three unusual openings in the temple’s pediment that may have been intended to let in moonlight, Artemis being the moon goddess; and the painted spirals of the capitals that inspired all buildings of the Ionic order that followed. “Digital technology allows us to try out different ideas in 3D and to imagine the temple and its surroundings in a way that’s not possible in 2D drawings or from other sources,” Denker says. “It’s the only way can we envision what it would have been like to visit this astonishing monument.”