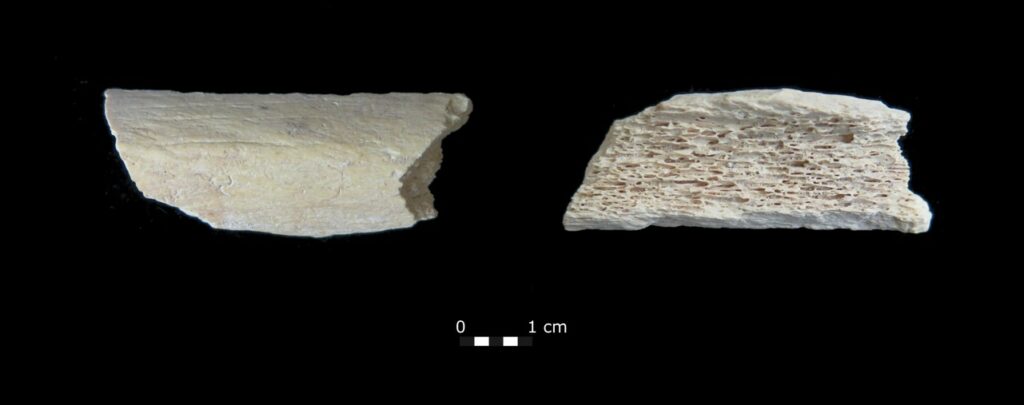

VIENNA, AUSTRIA—According to a statement released by the University of Vienna, anthropologist Emily M. Pigott of the University of Vienna used Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS) to analyze more than 150 unidentified bone fragments from Starosele rock shelter, which is located on the Crimean Peninsula. More than 90 percent of the bone fragments were identified as horse or deer bones, while some belonged to mammoths and wolves. Pigott and her team identified one two-inch piece of bone, however, as human. Study of this fragment with micro-CT imaging indicated that it came from a thigh bone, while radiocarbon dating showed that it was between 44,000 and 46,000 years old. Finally, DNA analysis identified that it came from a Neanderthal individual who was related to Neanderthals from the Altai region of Siberia, some 1,800 miles to the east, and to Neanderthals from central Europe. “Across Eurasia, very few human fossils are known from this crucial period when Neanderthals disappeared and Homo sapiens replaced them, and still fewer with genetic information,” Pigott said. She and her colleagues think that groups of Neanderthals may have migrated between Crimea, central Asia, and Europe during a period of favorable climate in the Late Pleistocene. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. To read about interbreeding between early humans, go to "Hominin Hybrid," one of ARCHAEOLOGY's Top 10 Discoveries of 2018.