The education of a navigator in the Marshall Islands, a Micronesian archipelago in the South Pacific, traditionally began by being blindfolded in a canoe. Young sailors learned to feel and intuit the motion of the sea before ever venturing out on ocean journeys. The deep Marshallese connection with waves and their movements reaches back more than 2,000 years to land-finding techniques used by the islands’ first settlers.

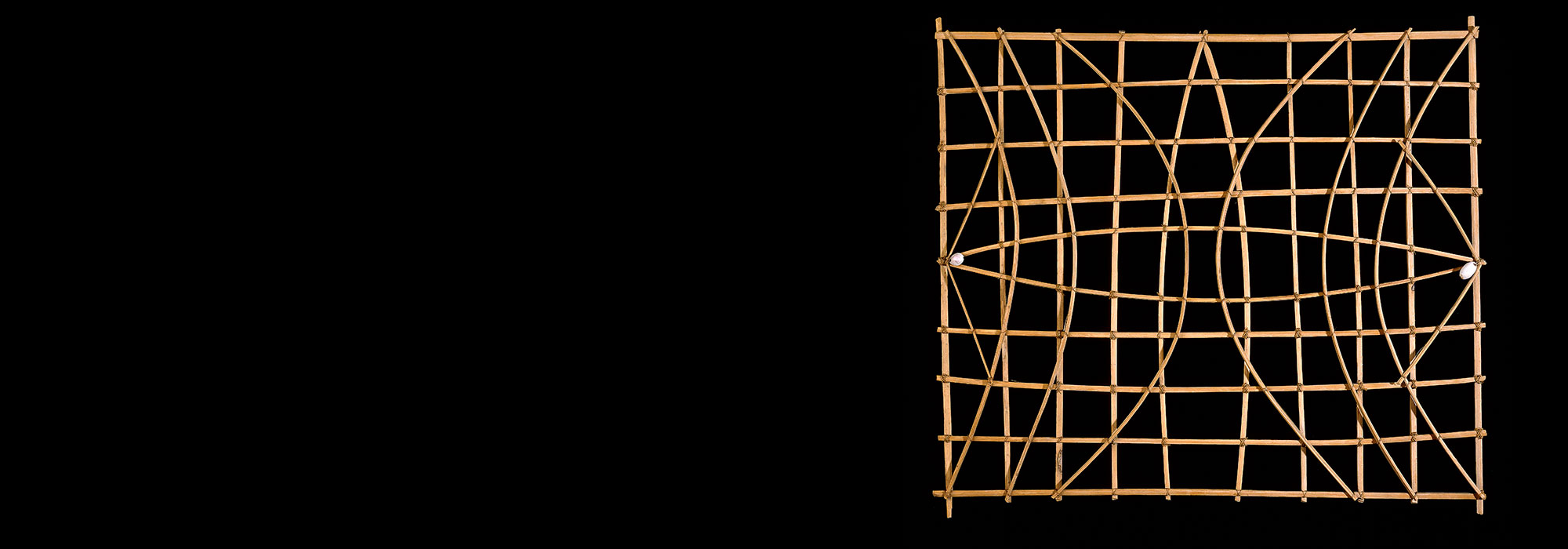

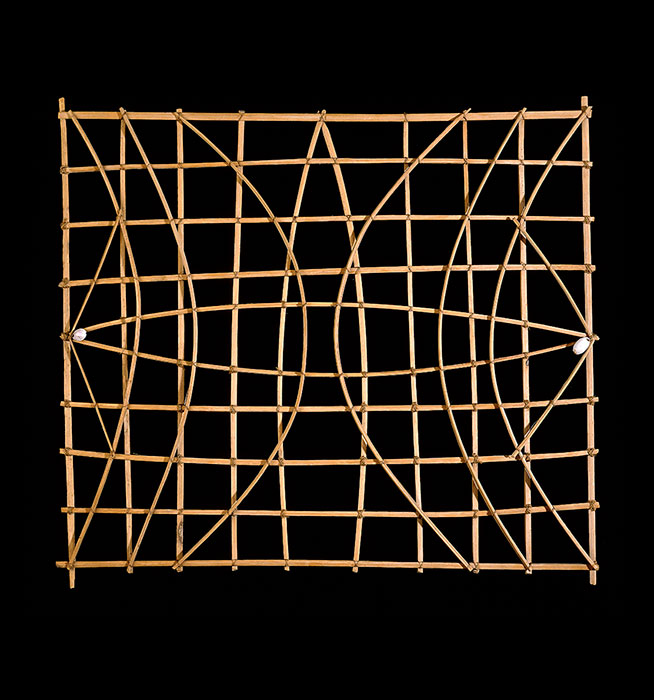

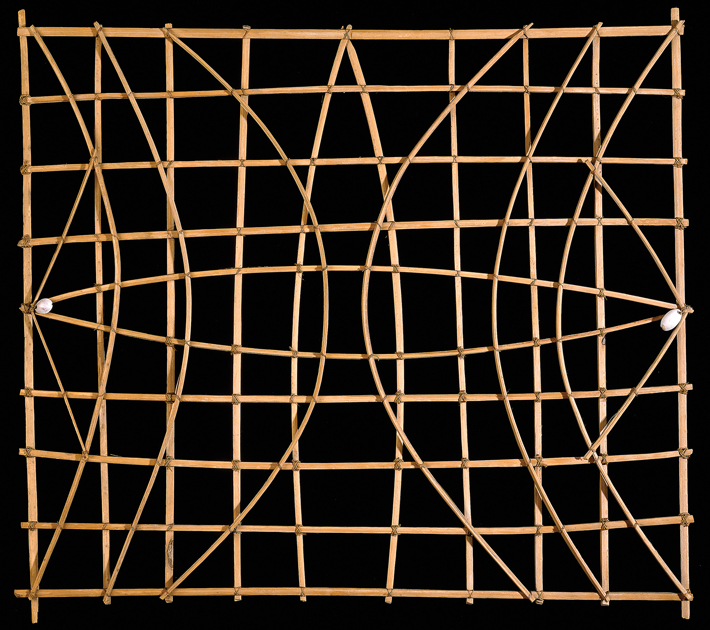

Scholars have identified two different types of Marshall Islands stick charts, wooden diagrams the Marshallese have been producing since at least the middle of the nineteenth century. The first and probably older type, shown here, contains abstract representations of how waves interact with bodies of land in general. The second type illustrates actual islands, often represented by cowrie shells, along with swell patterns identified and recorded by pilots. “There aren’t that many examples from across the Pacific of this kind of navigational knowledge being encoded or physically represented,” says anthropologist Joseph Genz of the University of Hawaii. He says the charts were used mainly as teaching devices rather than real-time way-finders. They help to impart perhaps the most crucial concept in the Marshallese navigational tradition, that of the dilep, or “backbone wave.” “People still describe the dilep as the most important wave to find,” Genz says. “It’s like a path you can follow to the next atoll. Instead of going landmark to landmark, you go seamark to seamark.”