On May 2, 2003, shortly after the invasion of Iraq, London’s Metropolitan Police raided an antiquities dealer and seized eight artifacts they believed had been obtained through illicit channels. It’s typically impossible to trace looted antiquities back to their original context. But in this instance, through a combination of good fortune and canny sleuthing, experts were able to close the case.

The artifacts—three ceramic cones bearing cuneiform inscriptions, one marble and one chalcedony stamp seal, a gypsum mace-head, a marble amulet pendant, and an inscribed river pebble—remained in police possession until late 2017, when they were brought to the British Museum and examined by St. John Simpson, a curator in the Middle East department. They appeared to him to have come from ancient Mesopotamia, and to have been produced by various cultures between the fourth and first millennia B.C. “It was clear they were from a big, important, multi-period site,” Simpson says. “That meant we had a short list of a very small number of places in southern Iraq.”

By an extraordinary stroke of luck, the previous year the museum had launched an excavation at just such a site: the ancient Sumerian city of Girsu, in modern-day Tello, in southern Iraq. Girsu was first excavated in the late nineteenth century and is among the world’s oldest known urban centers. Many inscribed artifacts from the site bear evidence of the birth of writing. Among the most important discoveries of the new excavation there, led by archaeologist Sebastien Rey, was of a temple called Eninnu, which was built around 2100 B.C. by Gudea, king of Lagash, the city-state of which Girsu was the capital. The temple was dedicated to Ningirsu, the Sumerian god of agriculture, thunder, and storms.

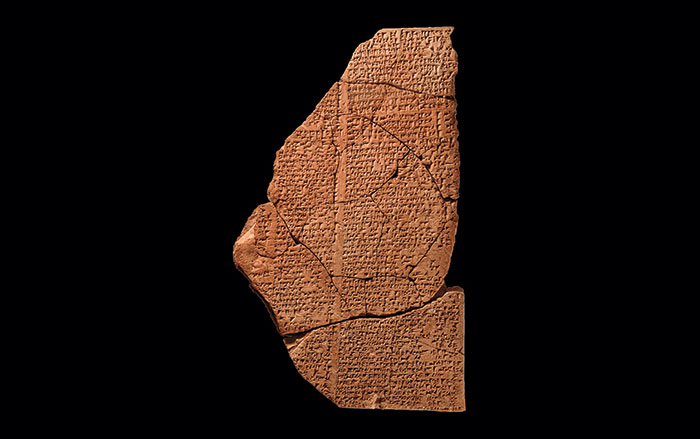

Soon after the artifacts arrived at the museum, Rey returned to London from Iraq. Simpson could hardly wait to show him the collection. “When I opened the box, I was shocked,” Rey recalls. “The first object I saw was an inscribed terracotta cone. It was identical to cones I had been retrieving in Tello a few weeks earlier.” All of the cones he had excavated bore an inscription that reads: “For Ningirsu, Enlil’s mighty warrior, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made things function as they should (and) he built and restored for him his Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” Says Rey, “One purpose of these objects was to say for eternity that this king had built a temple for his god.”

The London cones had the exact same inscription as those Rey had just discovered embedded in the temple’s mudbrick walls, with the text pointing up toward the sky so the god himself could read them. He was thus able to identify them as having come not just from Girsu, but from the very temple wall his team had been excavating. And as for the five other items seized from the dealer? Rey says these, too, were clearly from Tello. They are similar to other artifacts found at the site, though the amulet pendant and the marble stamp seal are older than the cones, and the chalcedony stamp seal is younger. Close to the temple, Rey and his team identified looters’ pits containing broken pieces of the very same type of inscribed ceramic cones, which had been left behind by the thieves. Rey learned from local tribal authorities that the looting had taken place just after the 2003 invasion. “All the objects went from the crime scene onto the black market within a very, very short period of time,” says Simpson. “Within about a month, they had been dug up, put in someone’s pocket, and transported to central London. It’s very rare that we can document that so accurately and establish that timeline so precisely.” With the items’ provenance convincingly established, they were returned to Iraq in August 2018 and will be housed in the country’s national museum.