A shipwreck designated archaeological site 1Ba704 should, say archaeologists, also be called Clotilda, one of the most notorious vessels in U.S. history. The path to identifying the wreck as the last ship to carry enslaved Africans to the United States has been challenging. And it began with the wrong wreck. In 1855, William Foster, a shipbuilder and businessman born in Nova Scotia and trained in the shipyards of the northeast, traveled south to Mobile, Alabama, where he built the schooner Clotilda. On the first of her 40 commercial voyages, she sailed to Havana from Mobile with unknown cargo. On her last, in 1860, she traveled to Mobile from Ouidah in the West African Kingdom of Dahomey, carrying 110 Africans destined for the slave markets of New Orleans. By then, it had been illegal to import slaves into the United States for more than 50 years.

The U.S. government first searched for Clotilda shortly after learning of her illicit voyage, but the endeavor proved fruitless—just after offloading his human cargo, Foster had torched and scuttled his ship. There have been periodic efforts to locate the vessel since then, but it was not until January 2018, when a ship in the Mobile River designated archaeological site 1Ba694 was speculatively identified as Clotilda, that archaeological investigation began. “It didn’t appear to me from the news photos and from the size of the wreck revealed by Google Earth to be a close match to what we know of Clotilda,” says maritime archaeologist James Delgado of the archaeology firm SEARCH. Close examination and documentation by SEARCH archaeologists soon revealed that 1Ba694 was built in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century on the Pacific Coast and was 183 feet long, far too large to be Clotilda. From the firsthand account of the launch, the official registration records, and insurance documents, Clotilda was known to have been less than half that size.

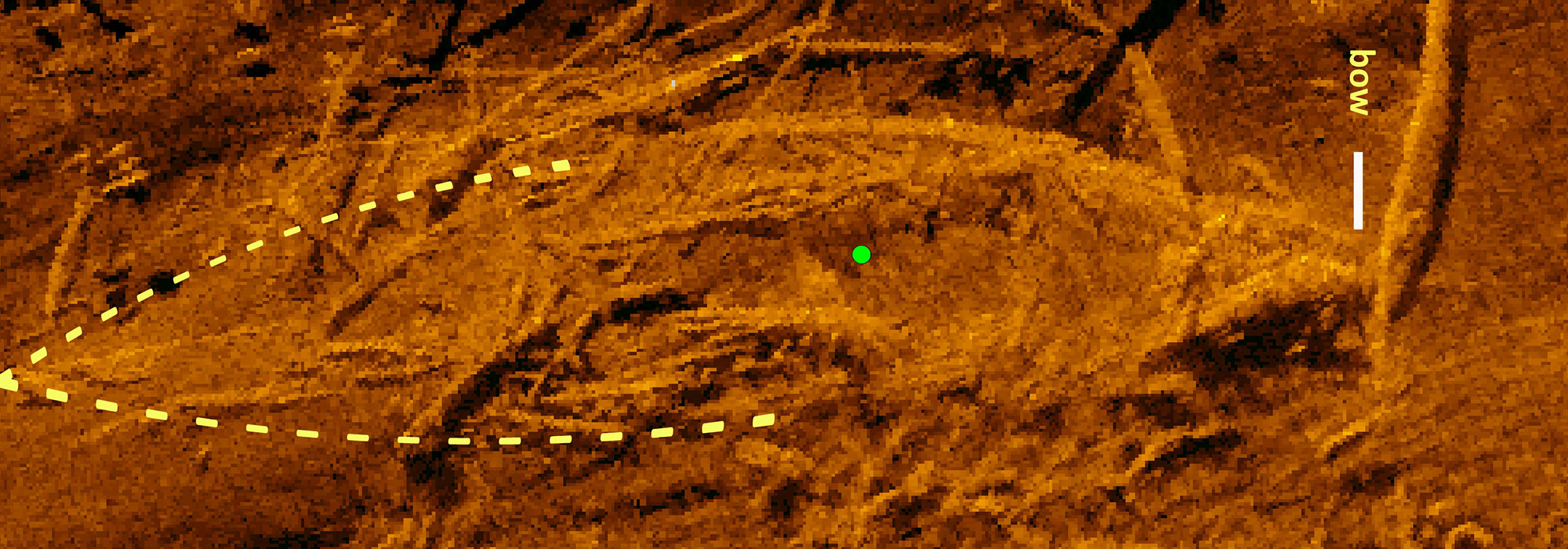

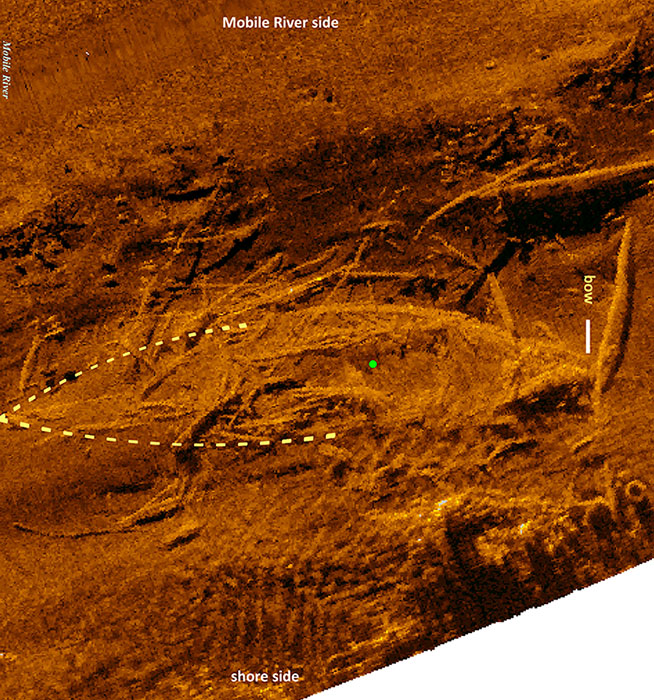

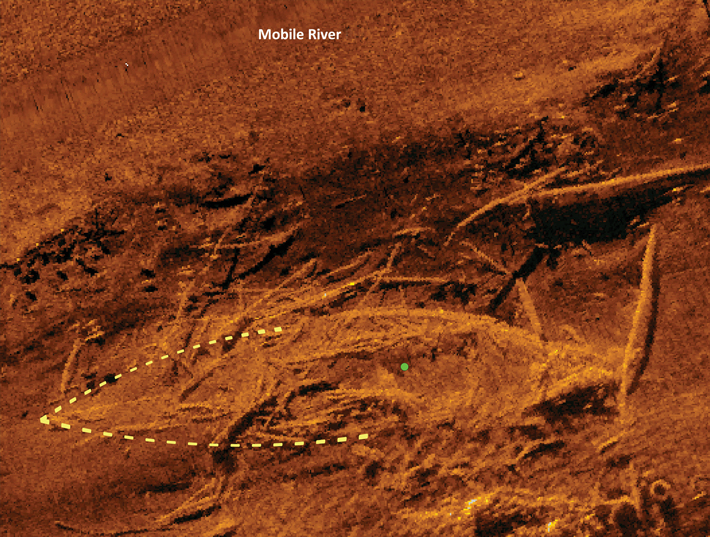

Having been enlisted to lead the project to try to find Clotilda, SEARCH, in cooperation with the Alabama Historical Commission, identified 14 potential targets for further exploration in a section of the river that had never been archaeologically surveyed. “Our priority was to focus our identification efforts on those wrecks that were possibly Clotilda,” Delgado says. “At first there were four candidates, then two, and then just one.”

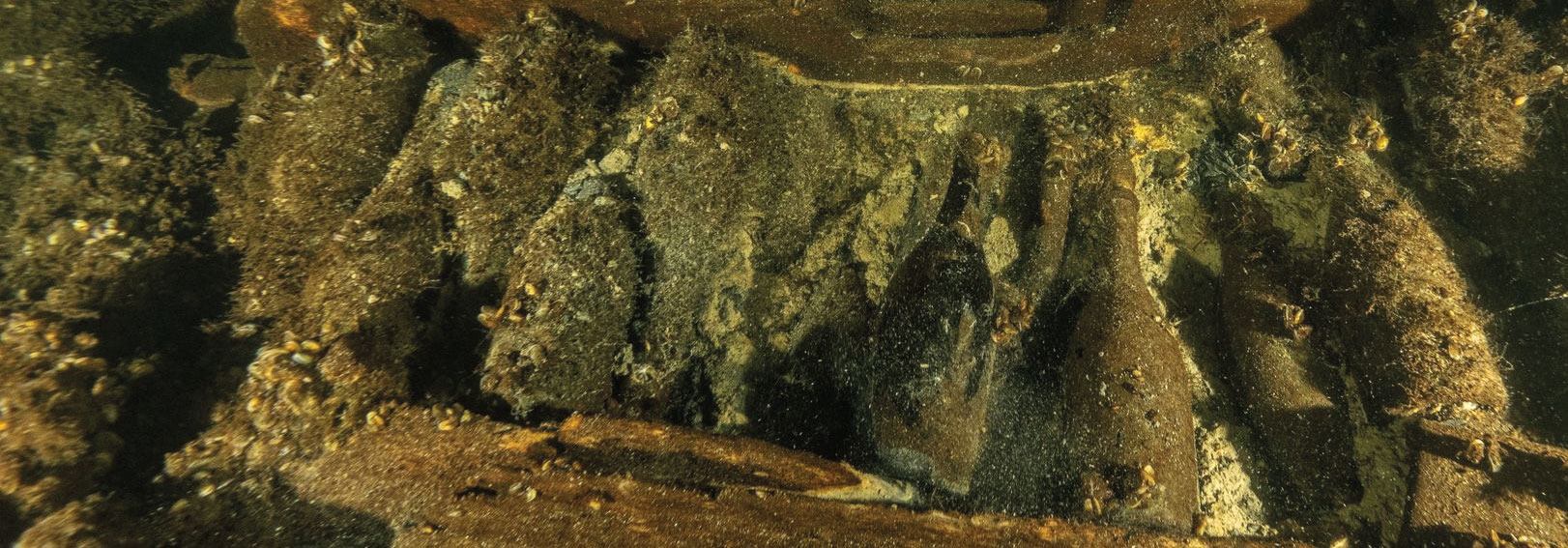

After concluding that 1Ba704 was the most likely candidate, the team gathered evidence in the cloudy, snake- and alligator-infested river. Extensive excavation was out of the question due to its potential to disturb the wreck. Instead, the divers took samples of barnacle-covered wood, gathered rusty iron nails, and measured the portion of the ship that was sticking out of the riverbed’s viscous mud. Analysis showed that the ship was built of locally harvested yellow pine and white oak, some of which was brittle and carbonized, suggesting it had been burned. The team also found evidence that the ship once had copper sheathing, a telltale sign of a vessel meant for deepwater ocean travel. Extrapolating from those parts of the wreck they could measure, the researchers estimate that the vessel was 86 feet long and 23 feet wide and had a 120-ton carrying capacity. Only eight schooners of more than 100 tons are known to have been built in the Gulf region during this time period, and 1Ba704 is the only one with the dimensions to match Clotilda and tonnage sufficient for the forbidden voyage to Africa.

Delgado acknowledges that the case is circumstantial and that, while further excavation may provide more evidence, there might never be a name or an artifact that confirms the ship’s identity beyond a shadow of doubt. Nonetheless, “if the level of preservation is as I suspect, then the physical evidence of the voyage will have survived,” says Delgado. “I’m moved by the resilience of the enslaved Africans. Clotilda’s story speaks to me as a human story, and also of how archaeology, which increasingly deals with slavery as a human institution, can provide new insights into the lives of the enslaved.”