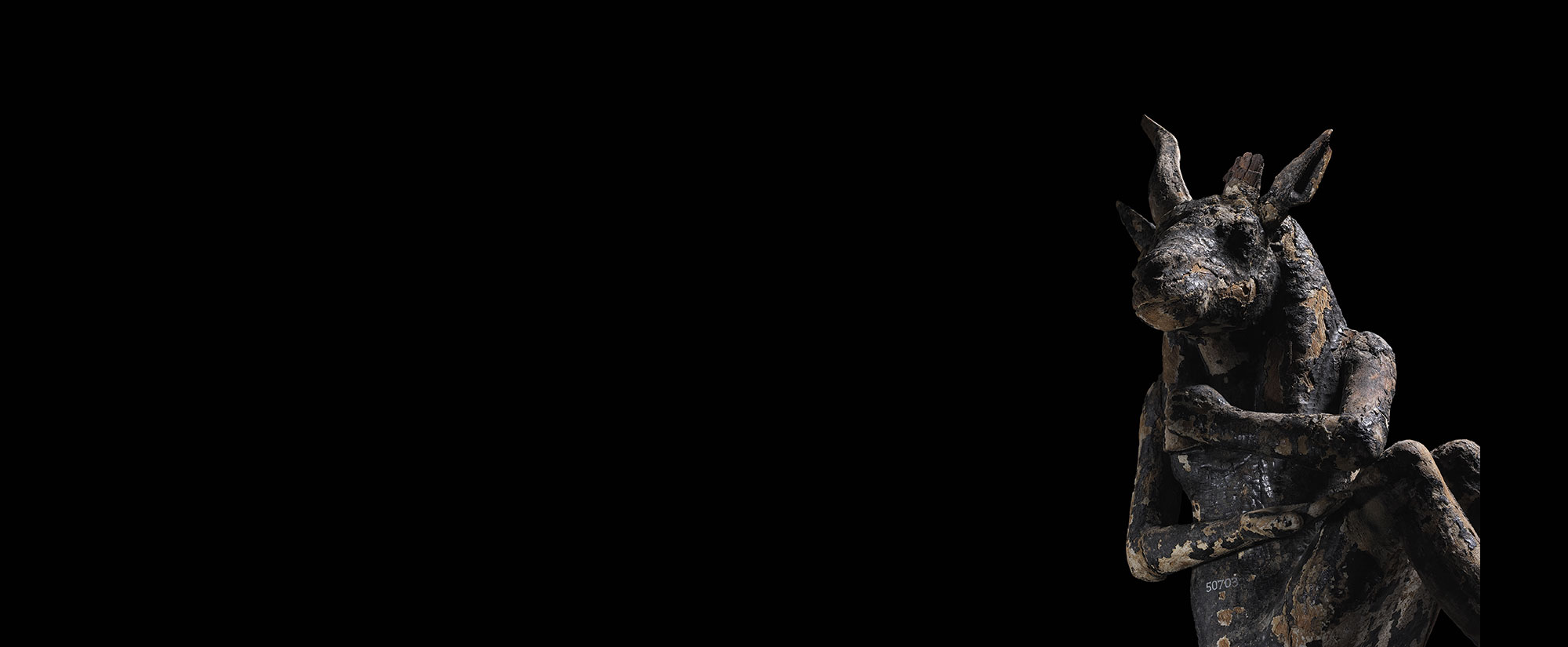

Domesticated horses are thought to have arrived in Mesopotamia around 2000 B.C., but before then, Sumerian scribes wrote of another type of equid, the family that includes horses, donkeys, and zebras. These animals were used to pull war wagons in battle and were given as royal dowries. The precise zoological classification of these animals, called kungas—a transliteration of the ancient Akkadian symbol meaning hybrid equid—had never been determined. Recently, a team of researchers analyzed the remains of equids that were discovered in a cemetery dating to between 2600 and 2200 B.C. at the site of Umm el-Marra in what is now Syria. They concluded that the characteristics of the animals’ skeletons do not fit with those of donkeys, which arrived in Mesopotamia from Egypt, where they were first domesticated around 3800 B.C. They also do not fit with those of a type of local wild ass called a hemippe that went extinct in the 1920s.

The team sequenced the genomes of the Umm el-Marra equids and two hemippes that survived into the early twentieth century as well as the genome of an 11,000-year-old hemippe discovered at Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. They determined that the animals buried at Umm el-Marra were hybrid offspring of female domesticated donkeys and male hemippes. This, says paleogeneticist Eva-Maria Geigl of the Jacques Monod Institute, is the earliest known evidence of animal hybridization. “Before they acquired horses, ancient Mesopotamians needed fast, strong equids that they could train to carry soldiers into battle,” says Geigl. “Donkeys are cautious, smart animals that will not run, especially not towards a hostile force, while wild asses, who are fast and less fearful, are virtually untamable.” By breeding kungas, Geigl explains, ancient Mesopotamians combined the optimal traits of both animals. However, while the offspring would have been healthy, they would also have been sterile, meaning the hybridization process would have had to be repeated for every generation.